The Vince Staples Show isn’t interested in being another surreal rap series”>

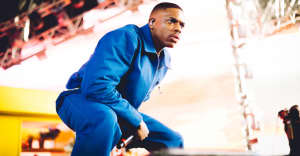

Still from The Vince Staples Show. Courtesy of Ser Baffo/NETFLIX

As a rapper Vince Staples chronicles memories of life in Long Beach with the kind of granite-like coldness only possessed by those who have experienced true darkness. “No matter what we grow into, we never gon’ escape our past,” he stated matter-of-factly on “Like It Is,” a song from his 2015 album Summertime ’06. His humor can be equally vivid: “Waiter still ain’t brought the chopsticks, should have brought the chopper” he ironically muses on the same album’s “Lift Me Up.” It’s this comedic sensibility that has garnered Staples just as much if not more attention than his rapping; he is an often hilarious and unique presence online and on camera, whether he’s recalling childhood memories or derailing a Coachella interview by calling out R. Kelly. He has joked that he would need “Joe Rogan money” to start a podcast and audio-only would seem a waste — he has always seemed destined to transfer his position as rap’s premier wit to the screen.

The Vince Staples Show builds on the 2019 web series of the same name, fleshing out the one-scene sketches into a fuller, more well-rounded sitcom. It takes the sardonic delivery of Staples’ raps and the humor he employs, both in and out of the studio, and transfers them to the screen. It’s part Curb Your Enthusiasm semi-autobiographical comedy, part hallucinatory deep dive into the paranoid mindset of its creator, and tonally unique. In a TV landscape where rap narratives have been covered with mixed results, The Vince Staples Show admirably treads its own path. Not a self-flagellating come-up diary like Dave or a formally ambitious exploration of its outskirts like Atlanta, Staples seems less interested in the rap world than a bigger sense of what it means to leave one world behind and attempt to start over in another.

Unlike those longer-running series, there are just five brief episodes (you can watch the whole thing in around 90 minutes). As a result, there are no long narrative arcs to the show with the focus instead on placing Staples in binds that it feels like only he could find himself in.

One episode, centered around a bank robbery, cuts the tension when the perpetrators recognize Staples and use it as an opportunity to catch up with an old friend (“How’s your mom?”). The hold-up becomes a chance to catch up as the robbers tell him they heard about the bank on the Drink Champs podcast and Staples outlines the difference between a heist and a robbery in the movies. George Clooney gets to do the former while Queen Latifah has to settle for the less distinguished description, he says. This episode, in particular, feels most like Staples’ viral interview clips, only in a very different setting.

Falling into these violent scenarios as he pursues legitimacy is something that has been a focus of Staples in his music. On his self-titled 2021 album, he rapped about worrying that meet-and-greets could turn into assassination attempts (“Sundown Town”) as well as tucking a gun in his shorts when he goes to the beach (“Taking Trips”), evocative and darkly funny images that seem to have inspired the new show’s direction.

The Vince Staples Show isn’t interested in being another surreal rap series”>

The Vince Staples Show isn’t interested in being another surreal rap series”>

Still from The Vince Staples Show. Courtesy of Ser Baffo/NETFLIX

The conflict at the center of The Vince Staples Show is between the status the rapper enjoys as a successful musician and the fact that he’s still a Crip, bound to the arbitrary carnage of his first home. He is rarely seen flustered during the show, even when confronted with inconvenience or, more seriously, extreme violence. It’s the other characters, a snotty bank manager or an aspiring musician sharing a jail cell with Staples, that give the show a dash of broad humor. Staples, a narrator of Long Beach life for over a decade now, simply floats above the madness.

The detached quality of Staples’s performance takes a minute to tap into. As an actor, Staples has appeared in the hugely popular Abbott Elementary and a superfluous White Men Can’t Jump reboot, though his acting remains natural in a way that could be read as amateurish. His unexpressive way of delivering dialogue, a continuation of his deadpan public persona, means scenes with his mom or girlfriend, especially during an episode centered around a cookout, don’t quite have the tender rapport needed to make them ring true.

Staples, a narrator of Long Beach life for over a decade now, simply floats above the madness.

Black-ish creator Kenya Barris worked on the show alongside Staples but there is little of his satire of the middle class at play here. You won’t find Staples playing a cartoonish figure, frustrated and impotent in front of loved ones. Instead, the show visuals the neuroses and fears of its protagonist; it excels when it leans into this bizarro mode. This is a world in which a laundromat doubles as an illicit place to get BBL surgery and Rick Ross offers to help fund your sugar-free cereal business, and where you’re taken on a dreamlike visit to a theme park while Staples searches for a chicken spot, paranoid that he is being followed by a fluffy mascot. The threat of danger can be more immediate: A day spent helping educate a class of young kids on the life of a creative is upended when one of the kids snitches on Staples and his father turns up to school with a gun.

That space between being fully in the light and trying to avoid the shadows behind him is rich ground for Staples. While there has always been humor in his music he often leads with, or is certainly most recognized for, the darker subject matter. The Vince Staples Show flips that paradigm around and masks the violence with humor, illuminating his starkest memories with a knowing wink.