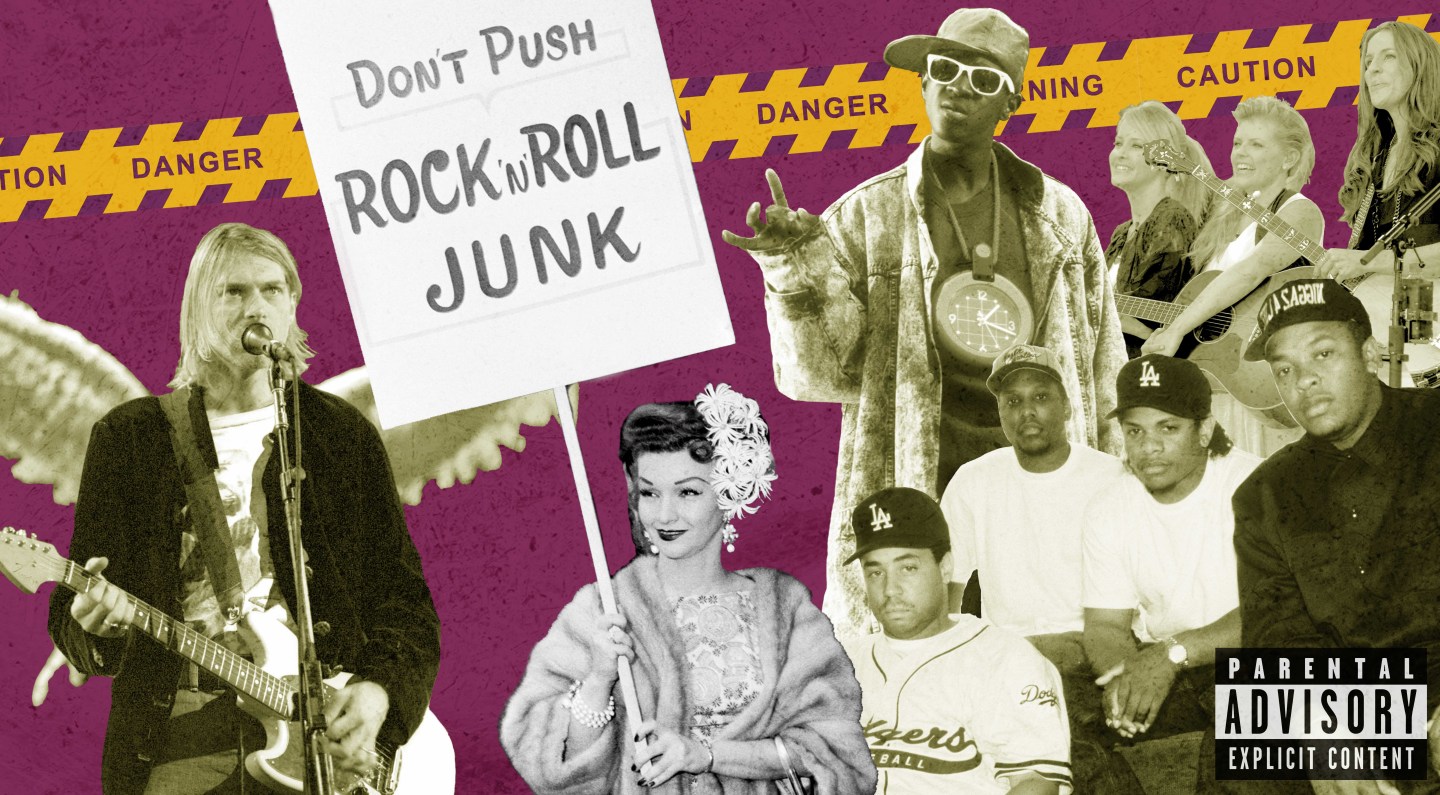

Pop music sounds more homogenous and inoffensive than ever before. Venture capital hoovers up publishing rights and record labels lean hard on TikTok trends, desperate to build as many data points as possible for a song that sells. As a result, even most of the music that stirs up controversy or much-needed discussion feels designed to do so by a committee of suits.

The past few years have increased our appreciation for songs that reach a mass audience and organically push an issue from underground and into focus to the consternation of the majority and/or those who control the levers of power. Whether that’s women’s rights, free speech, police brutality, or systemic racism, these songs remind us that popular music has a role in real change.

If you glance through the list, you’ll notice that not all of the songs are strictly pop. For our purposes — and to get a wider cross-section of music — we’ve defined “pop” as “popular.” In other words, songs that found a large audience thanks in part to the subject matter they cover. Some songs were released just a few years ago, while others are older than civil rights in America. But in all cases, these songs have turned the prospect of a more liveable world into a tune that you can’t get unstuck from your head.

Frankie Goes To Hollywood: “Relax”

40 years after its release, “Relax” is in a league of its own apart from other globally recognized pop classics: even though everyone knows all the words, it’s not something you’d ever consider putting on at a wedding. It’s just that deviant, a four-minute tongue-in-cheek tantric workshop and celebration of the orgasm. More importantly, though, it’s a smash hit pop song released during the height of the AIDS crisis by openly queer artists (a rarity, if not an outright first for the Billboard charts) who refused to be cowed or shamed for broadcasting their sexuality. — JD

The Replacements: “Androgynous”

The gorgeously ramshackle piano ballad in the middle of The Mats’ classic Let It Be was further ahead of its time than anyone would have hoped. Paul Westerberg sings about gender non-conformity and queer love with a frankness, compassion, and defiance that’s still striking today — “Something meets boy, and something meets girl / They both look the same, they’re overjoyed in this world” — but there’s a real sadness in hearing him ask, repeatedly, “Tomorrow, who’s gonna fuss?” in a song that’s turning 40 this year. Tomorrow should be here by now. — ARR

The Coup: “5 Million Ways To Kill A C.E.O.”

Before he was taking his anti-capitalist message to the big screen in films like Sorry To Bother You, Boots Riley was fronting the equally radical rap group The Coup. “Toss a dollar in the river / And when he jump in/ If you find he can swim / Put lead boots on him and do it again,” Riley raps over a cosmic funk backdrop as he aligns himself with the Black Panthers and stands up for victims of police brutality and modern slavery. It led to The Coup being labeled as “loathsome” by at least one right-wing commentator and others to think that stopping at five million ways is simply not thinking hard enough. — DR

Body Count: “Cop Killer”

When Ice-T wrote the lyrics for Body Count’s “Cop Killer,” he was protesting unfettered police brutality against the Black community using a “fight fire with fire” mindset. But following the 1992 Rodney King riots, the hardcore punk song kickstarted a political firestorm of unprecedented proportions. Denounced by the likes of the NRA’s Charlton Heston to President George H.W. Bush, the controversy led to their self-titled debut being pulled from shelves and a nationwide police boycott of Warner Bros. Records — SS

System Of A Down: “B.Y.O.B”

This wasn’t System of a Down’s first anti-Iraq War song — that’s 2003’s more didactic “Boom!” — but it was the one that broke through. The hypnotically poppy chorus is there to draw crowds in, as seductive and misleading as NFL half-time ads that make joining the Marines seem like a year studying abroad. But the message is so urgent that, by the end, Serj Tankian and Daron Malakian are cutting the party short mid-sentence to scream murder at the men who order death from behind their desks: “Why don’t the presidents fight the war? / Why do they always send the poor?” — ARR

ANOHNI: “Drone Bomb Me”

ANOHNI’s music has always contained strong political undercurrents, but on 2016’s HOPELESSNESS, she traded the nurturing soul sounds of her work with The Johnsons for confrontational messaging underscored by apocalyptic production from Oneohtrix Point Never and Hudson Mohawk. Written in the language of a love song from the perspective of a nine-year-old Afghan girl who’s watched her family’s murder by a U.S. drone strike and longs to die in the same fashion, “Drone Bomb Me” is a scathing critique of Obama’s foreign policy and, more timelessly, an uncomfortable exploration of the American public’s complicity in our government’s crimes. — RH

Eminem: “Stan”

It’s beyond perverse that Eminem’s most impressive artistic achievement, a profound reflection on parasocial relationships and the weirdness of fame, ended up, years later, having its name co-opted by the same obsessive fans he was trying to comprehend and critique. “Stan” is intentionally visceral. The murder-suicide at its core is dealt with as unflinchingly in Eminem’s verses as it is in its at-the-time controversial video. But there’s a more pernicious reason no major label could release anything like “Stan” today: nobody would risk alienating the terrifyingly obsessive audience the song addresses. — ARR

Billie Holiday: “Strange Fruit”

Often referred to as the first great protest song, Billie Holiday’s 1939 song is about racist lynchings. It’s a song that boldly portrays the violence of the act and led to the FBI doggedly pursuing the singer. Nobody can looks away as Holiday sings of “blood on the leaves,” dropping one haunting image after another, the pain in her voice palpable. Unlike many protest songs, it is not one to rally the disaffected, instead taking an arguably more effective route and shaming those who oppress them. — DR

Bruce Springsteen: “Born in the USA”

Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” has been a political rally favorite for decades, despite the song being originally written as a clear condemnation of America’s mistreatment of Vietnam veterans. By extension, it was also a pointed criticism of the same Washington war hawks that weaponized people’s patriotism against them, especially those from blue-collar backgrounds who also couldn’t dodge the draft. But with its ironic title and rousing rock n’ roll chorus, “Born in the U.S.A.” is still misinterpreted as an fervent pro-America anthem by anyone who doesn’t listen to the lyrics or anything Springsteen himself has said. — SS

Fela Kuti: “Zombie”

Several songs on this list led to governments seeking to monitor or outright destroy the reputations of the artists who made them, but in writing “Zombie,” Fela Kuti suffered a direct and violent reprisal from the Nigerian government. The song took aim at the slaving obedience of the country’s soldiers and became a hit within Nigeria for the hugely popular Afrobeat pioneer. Soon after its release, the military razed Kuti’s commune, injuring the artist and killing his mother in the process. Kuti’s response? Bringing his mother’s coffin to a military barracks in Lagos, and of course, writing the songs “Coffin for Head of State” and “Unknown Soldier” about the incident. — JD

Green Day: “American Idiot”

Green Day had toyed with anti-government, anti-surveillance state lyricism before American Idiot, but it’s on this record that they decided to go all out. The album, and its title track, are shrewd critiques of Bush-era politics and media news propaganda around the Iraq war, emphasizing the state of post 9/11 disillusionment and its ensuing, ongoing mass delirium. “And can you hear the sound of hysteria? / The subliminal mindfuck America.” Nothing about it is subtle, and that’s the point. — CS

The Chicks: “Not Ready To Make Nice”

Had it not been for Betty Clarke’s Guardian review of their show at London’s Shepherd’s Bush Empire in 2003, maybe the Chicks never would have ended up in the (sometimes miserably literal) crosshairs of right-wing country fans. That night, Natalie Maines said she opposed the Iraq War and that she was ashamed to share a home state with George W. Bush. She was right then, and she was right three years later when she belted, over a sweeping, inescapably rousing country-rock song, that she wasn’t sorry for a moment of it. The establishment isn’t usually kind to people like Maines, but history always is. — ARR

Childish Gambino: “This Is America”

When Childish Gambino released “This Is America” in 2018, the country was still waking up to the systemic racism imposed upon Black Americans, including gun violence, police misconduct, and pop culture-proliferated stereotypes. But with pointed lyrics delivered over ominous trap beats that flip into joyful harmonies, “This Is America” and its provocative music video created a watershed moment in pop culture by combining Black American stereotypes by using joints and viral dances, alongside unsettling scenes of brutal violence referencing mass shootings, Jim Crow, and the guns regularly used to murder Black bodies — with Glover at the center of it all. — SS

Public Enemy: “Fight The Power”

You could easily argue that Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” is one of the most influential protest songs of all time, as a fierce and defiant anthem against institutionalized racism that continues to be played to this day. Confrontational and straight-to-the-point, the 1989 single was written for Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing at a time when racial tensions were about to come to a boiling point under the Reagan and Bush administrations. And it’s reflected within production that proudly incorporates James Brown samples and a speech by civil rights activist Thomas “TNT” Todd, alongside Chuck D’s biting commentary about the government’s indifference to the inner city struggle. — SS

The Beatles: “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”

The world that John Lennon describes in “Lucy In the Sky with Diamonds” mentions tangerine trees, marmalade skies, and girls with kaleidoscope eyes. Rocking horse people eat “marshmallow pies,” and the flowers go oh so incredibly high. The only way this song could be more explicitly about drugs would be if the band had referenced psychedelics in the title –– except, oh wait, they already did, with its initials! Even Lennon’s feeble attempt at comparing the track to Alice in Wonderland just further emphasizes this notion; we can access Lewis Carroll’s universe anytime, with the psychedelic of our choosing. — CS

Gil Scott-Heron: “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”

Legend has it that Gil Scott-Heron wrote his incendiary indictment of postmodern capitalism while watching baseball in his college dorm room in 1969. Backed by a funk rhythm section and a fluttering flute, he weaves a head-spinning lattice of pop culture references and TV ad taglines to define everything the revolution will not be, all the way up into the track’s final line: “The revolution will be live.” Without the aid of radio play, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” spread via word of mouth and quickly became a national rallying cry for Black liberation. — RH

2 Live Crew: “Me So Horny”

Released in 1989 when televangelism was beamed into millions of homes and it seemed as though the far right would rule for another generation, “Me So Horny” fulfilled nearly every stereotype about rap music held by frightened churchgoers. The song’s unabashedly pornographic content led Florida to ban sales of the single and its album, As Nasty As they Wanna Be, on obscenity charges, a controversy that helped the song peak at No. 26 on the Billboard Hot 100. But its legacy was solidified when the Supreme Court dissolved the ban, marking a significant victory for free speech and artist’s rights. — JD

N.W.A: “Fuck Tha Police”

Straight Outta Compton, the founding document of West Coast gangsta rap, was maligned by the establishment upon its 1988 release for its brazen glorification of criminal activity, but its most resonant track is a protest song. A defiant, no-holds-barred tirade against police brutality and racial profiling, “Fuck Tha Police” earned N.W.A. censorship from radio stations across the globe and a censure from the FBI, but Straight Outta Compton went triple platinum nonetheless. — RH

George Michael: “Outside”

Michael explicitly stated his love of the sex in public when he released “Outside.” “I think I’m done with the kitchen table, baby” he sings playfully over the pumping 2008 disco tune casting his eye “back to nature, just human nature,” instead. The song played into the real-life drama surrounding Michael at the time, arriving not long after he was arrested by an undercover police officer for performing a “lewd act” in a Beverly Hills public toilet. The “Outside” video, complete with Michael dressed as a leather-gloved police officer, was a defiant middle finger to the homophobic tabloid handling of the story. — DR

Peter Paul and Mary: “Puff The Magic Dragon”

Peter, Paul, and Mary have denied that their hit children’s song “Puff the Magic Dragon” is about drug use, but does it really matter? Originally written to be about the passage of childhood and leaving the imaginary world of your youth behind, listeners have taken it upon themselves to over-analyze the simplistic, yet whimsical, lyrics as something deeper, as children’s lyrics are wont to do: the references to “Puff” and “autumn mist”; rolling papers are found within the character of Jackie Paper; and “Hanah Lee,” they speculate, is an allusion to the Hawaiian town Hanalei, famous for its strong marijuana. — CS

Ian Dury & the Blockheads: “Spasticus Autisticus”

Ian Dury wrote this song in response to the UN designating 1981 as the Year of the Disabled, rightfully mocking the move as insensitive and pouring scorn on the short-sighted if well-meaning thought behind it. The song is deliberately antagonizing, using a term that in his native U.K. has long been used as a slur for those with disabilities. 40 years on however, when disabled people are still statistically proven to be more likely to live in poverty, Dury’s message acts as a reminder that token gestures are never good enough. — DR

Paul Robeson: “Joe Hill”

Penned as a poem by Alfred Hayes in 1930, arranged for music by Earl Robinson in 1936, and recorded by iconic bass-baritone Paul Robeson shortly thereafter, “Joe Hill” is at once a murder ballad, a ghost story, and a union anthem. Hayes’s poem imagines a posthumous meeting with Joe Hill, a labor activist executed by firing squad in 1915 for a double murder widely believed to be a framing. The song’s narrator reacts to Joe’s apparition in disbelief, but Joe responds emphatically that he lives on wherever workers rise up to organize. An unlikely Billboard-charting hit (as part of Robeson’s 1943 album Songs of Free Men), the song worked as intended, immortalizing Joe Hill as a universal symbol of resistance. — RH

Loretta Lynn: “The Pill”

Lynn was an icon of country music in 1975, the year she released a defiant and brightly humorous song called “The Pill.” Its celebration of the freedom that comes with birth control — as well as Lynn’s refusal to be a broodmare for her husband — were seen as a heretical embrace of the feminist movement by the country music establishment. Bans across country radio swiftly followed and may still endure to this day; however, they’ve done little to stop “The Pill” from entering the country music canon as one of Lynn’s most beloved and important songs. — JD

Nirvana: “Rape Me”

Sure, “Rape Me” is an anti-rape song, as declared by Kurt Cobain, but the title was enough to cause the world to lose their minds when it was first released. Cobain explained that the song is written from the point of view of the victim, with the abuser eventually being punished for their actions. Nuance is all but completely lost with a song literally titled “Rape Me,” though, and the lyrics don’t exactly handle the situation delicately. Whatever his intention, he ended up provoking the people he’d intended to provoke. — CS

Randy Newman: “Rednecks”

Randy Newman is one of pop music’s greatest enigmas, a master of both G-rated warmth and acidic cynicism. In character, he’s called for the U.S. to bomb the planet into oblivion and suggested mass suicide for the vertically challenged. But 1974’s “Rednecks” is both his most compelling and problematic work of satire, a genius work of singalong popcraft with a heart that pumps ironically racist bile. The song is narrated by a proud southerner who is inspired by segregationist Georgia governor Lester Maddox’s appearance on The Dick Cavett Show to paint an idyllic portrait of the south liberally seasoned with the phrase “keepin’ the n***ers down.” In its final verse, however, Newman turns his poisoned pen on northerners who feel superior to southern bigots, reminding us that “the cage” of Black poverty and mass incarceration is as endemic above the Mason-Dixon line as it is below. The point may seem obvious now, and the song certainly couldn’t be written today (for good reason), but its message was essential 50 years ago, as the struggle for equality moved beyond the Southern Civil Rights Movement to the issues that plagued Black Americans nationwide. — RH