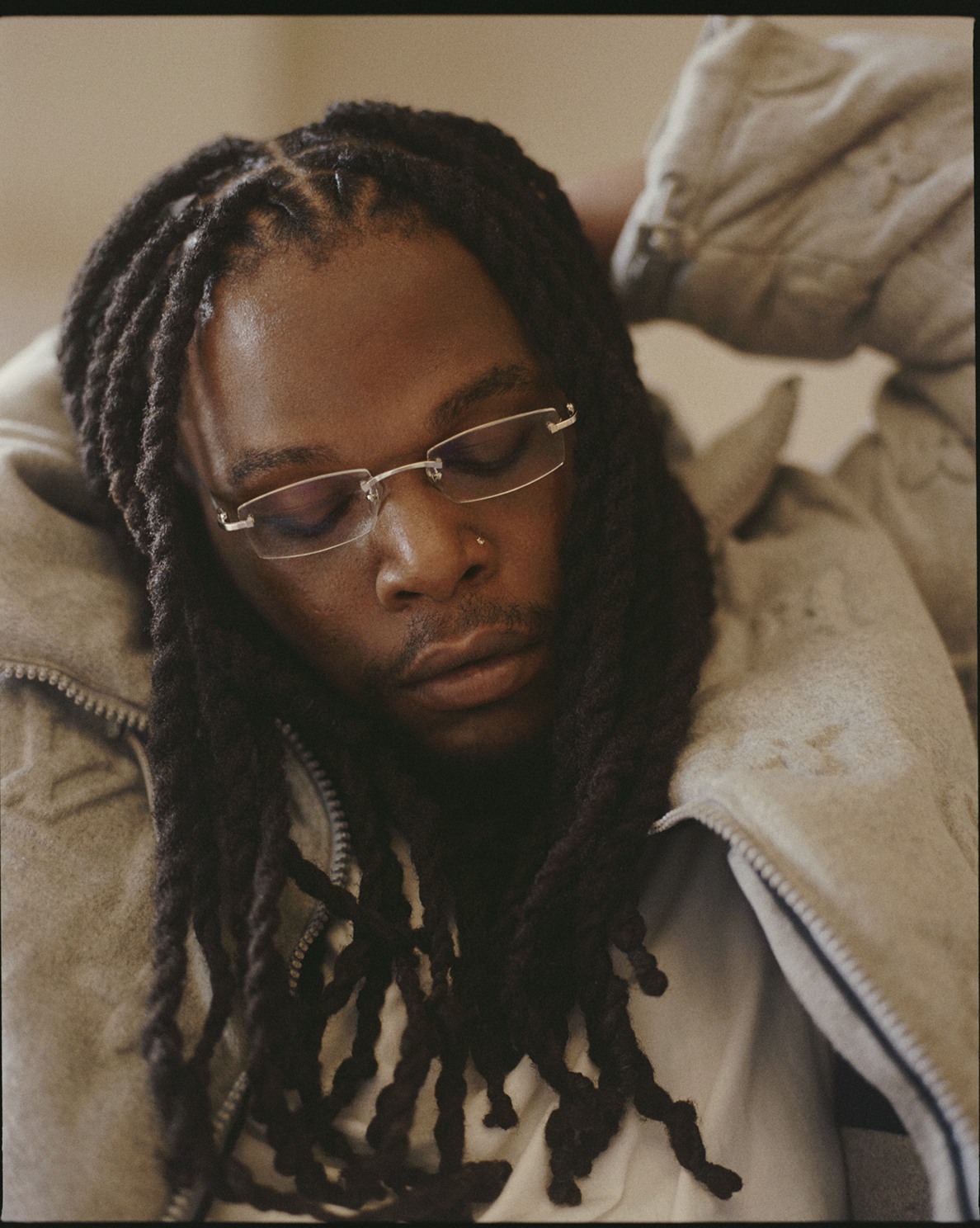

Micaiah Carter

$ilkmoney is locked on a memory. It’s sometime after 2016, when he was part of a buzzing rap crew called Divine Council, signed to Epic Records. They’re speaking to an executive at the label. Over our video call, $ilkmoney brushes his flowing dreads from his face, puts his freshly-sparked joint to the side, and comes close to the camera. “This motherfucker said ‘we’re not too pressed about you dropping music’ and used [Chicago drill rapper] King Louie as an example. He said ‘Louie’s been signed for five years and hasn’t dropped an album, but you know what? He comes up here and he makes us laugh.’” Silk pauses, mouth agape. “I thought that was the craziest shit.”

That deal was poisoned. Despite having a viral hit that preceded their Epic signing (“P. Sherman (PS42WW$)”) and an André 3000 feature on the October 2016 remix of “Decemba,” Divine Council dissolved in 2017. Undeterred, $ilkmoney began releasing solo projects with amusing, eye-catching titles: I Hate My Life and I Really Wish People Would Stop Telling Me Not To and G.T.F.O.M.D: There’s Not Enough Room for All You Motha Fuckas to Be on It Like This. But it was $ilkmoney himself that was truly gripping: his gravelly, acerbic stream of consciousness covered everything from phallic preoccupations to generational trauma with a pimp swagger and street prophet’s urgency. His ear for weird beats, from mildly possessed lo-fi to space-station cloud rap, further kept things unpredictable.

Micaiah Carter

Unsurprisingly, $ilkmoney has a strong aversion to being pigeonholed. He doesn’t mind talking at length about how psilocybin influences his freewheeling and liberated lyrics, but clearly doesn’t want to be known as a “mushroom rapper.” He’s grateful for his 2019 TikTok hit “My Potna Dem,” but is intent on building a much bigger legacy. And while he’ll forever be grateful to his big three — Curren$y, Lupe Fiasco, and Lil B — for helping him fall in love with rapping, if he can’t do it in his own voice, he won’t do it at all.

It’s immediately apparent that no one but $ilkmoney could have made his excellent new album Who Waters the Wilting Giving Tree Once the Leaves Dry Up and the Fruits No Longer Bear?. It’s unlikely to convert any naysayers — this is the most $ilkmoney project yet, more provocative, personal, and puerile than any other. It makes for some of his best music yet, too, whether he’s tenderly ruminating on love on “FIRST I GIVE UP, THEN I GIVE IN, THEN I GIVE ALL” or snarling at the crab-in-the-bucket mentality of the music industry on “OOOPS, HONEY I SHRUNK MYSELF WITH THE HONEY I SHRUNK THE KIDS RAY MACHINE AND CRAWLED INTO YOUR DICK.”

A key quality I’ve noticed in $ilkmoney’s music and during our conversation is that he’s fiercely protective of what he loves: Black people, Black art, and staying rooted. He comes from a musical family, and recalls his father, now passed, dropping him off at choir practice when he was seven. “He always told me if I don’t sing, I don’t eat. And I was a fat kid. So clearly I sung a lot.” He gets the most animated when talking about his small circle of collaborators including Khalil Blu, his longtime producer who lends a subtly epic flair to the new project with a suite of sample-flips pulled from progressive soul, old movies, and more.

Ahead of the new album, released on Lex Records, The FADER spoke to $ilkmoney about humor, the industry, and being an artist in a brave new world.

The FADER: Talk to me a little bit about your ambitions, because so much of your music is understandably quite hostile to the music industry, given your own experiences with it. What’s your personal glass ceiling?

$ilkmoney: I feel like my glass ceiling is the same for a lot of musicians, because it feels like for some time I’ve been doing this thing. If you want to talk about the “My Potna Dem” TikTok thing, I always say it wasn’t supposed to happen because there isn’t a company to benefit off of that. That’s not how the music industry works. They’re not gonna allow you to make $700,000 off of a song if they’re not getting a piece of it. It’s just the glass ceiling comes into play where it’s like, “All right, you got this far, buddy. But to get further, we’re gonna need you to sign this. And we’re gonna need you to give up this and we’re gonna need a piece of this and this, that and that.”

At the end of the day, I just want to be heard. I can’t beat the algorithm. I can’t fight the engagement suppression. It’s like the tech industry runs hip hop today and music is this secondary thing. You gotta be funny. You gotta be a streamer. You gotta play video games for hours and then go, “Hey, like the song, guys!” and then make people go, “Oh, yo, he’s actually pretty good at making music.” So that’s the glass ceiling: What are you willing to compromise in order to be heard?

“He always told me if I don’t sing, I don’t eat. And I was a fat kid. So clearly I sung a lot.”

What made you sign with Lex?

A litany of things. I’ll put it like this: they weren’t greedy, and that off the top shows me that this is a company that’s willing to work with me and help me foundationalize a future for myself, whether it be artistically, creatively or financially. It just felt like a company that is following the code of old record labels where they’re signing off of the music. They’re not signing off of, you know, you got, you got a hundred thousand, 150,000 followers. [sarcastically] You can do something with that. A lot of these artists are not really artists. They’re just influencers that sell themselves with music.

There are a couple of moments on the new project where your sense of humor reminds me of Paul Mooney.

Is there a bar that stands out?

Micaiah Carter

The Jonathan Majors and Diddy lines on “Probably Wouldn’t Be Here…”

[Laughs] Yeah. That song was my way of saying, oh, now you want to come home. In that song, I said, “America’s favorite nigga gets replaced and back to the plantation.” With Black personification and acting, there are the chosen niggas. These are what America would like to be the everyday personification of what a nigga is. You know, a nigga like Jonathan Majors worked his ass off to be around them crackers. And then he finally get around them and then they do them like that. And he want to come home and they expect us to have the Meagan Goods for him. And show up with him to that court case and be like, “we here, black man.”

Same with Cynthia Erivo. I’m on that ass. I’ve seen all them little nigga jokes you were making.

This captures what I love about your music: the hate is nuanced and directed at people, institutions, and ways of thinking in a very specific way.

Black people got exactly what we want. We went our whole life wanting to be depicted and personified in media. Now that’s all we get, and I hate it. I’m like, “God damn they did us like that?!”

I’m trying to cover those topics, even when I said, “The cost of a stream is non-existent unless you make it with fishes in it / Besides you paid the amount equated to time and attention,” because a stream is just engagement. I’m writing another album right now covering a lot of fucking topics: A.I., streaming, engagement. Because engagement don’t matter. A like holds the same value as a dislike.

“It’s like the tech industry runs hip hop today and music is this secondary thing. You gotta be funny. You gotta be a streamer.”

How does that make you feel as an artist?

I think that’s the result of how we let hip-hop down. It feels panhandle-y to me. Every time I see a rapper awkwardly sitting next to a streamer, I think, you might as well put some Ray Charles glasses on and go, “drop a stream in my cup! Drop a like, drop a comment, drop a share, nigga!” That shit looks beggy when you gotta go to this motherfucker who knows absolutely nothing about hip-hop to sell your album to a demographic of people who don’t even like hip-hop, they just like rappers.

How did you land on the concept of The Giving Tree?

Every time I drop an album or do anything, I give my all to it. I give every single thing I have within me. I give my hatred, I give my love, I give my jovial side, my community, I give everything that is that encompasses what Murphy Graves is, fuck $ilkmoney. And I wrap it all into a present, and boom, it’s an album.

Molding it around The Giving Tree, I feel like every single one of us are givers in our own way, whether you give your all to your passion or your dream or your children or whatever, we’re just giving and giving and giving, whether we receive what we feel like we gave back in equal value or whether we receive nothing at all. That’s what I feel like about hip-hop. I give my all to hip-hop and whether I feel like I’ve received what I’m supposed to receive from hip-hop or not, at the end of the day, hip-hop owes me nothing and I owe my all to it.