This story is part of our fall 2025 series, Offline, where we investigate IRL spaces and explore our relationships with music and the internet.

In 2022, Bandcamp was purchased by Fortnite publisher Epic Games. A year later, the beloved music marketplace was sold to music licensing platform Songtradr, which soon fired 16% of the company’s workforce, including the entire Bandcamp union. Independent musicians and labels, already surrounded by precarity, now had to reckon with the prospect of a critical source of revenue suddenly getting sold for parts or disappearing entirely. Enter Subvert.FM, a Bandcamp successor that offers artists not just stability, but unprecedented power, in the form of a co-op.

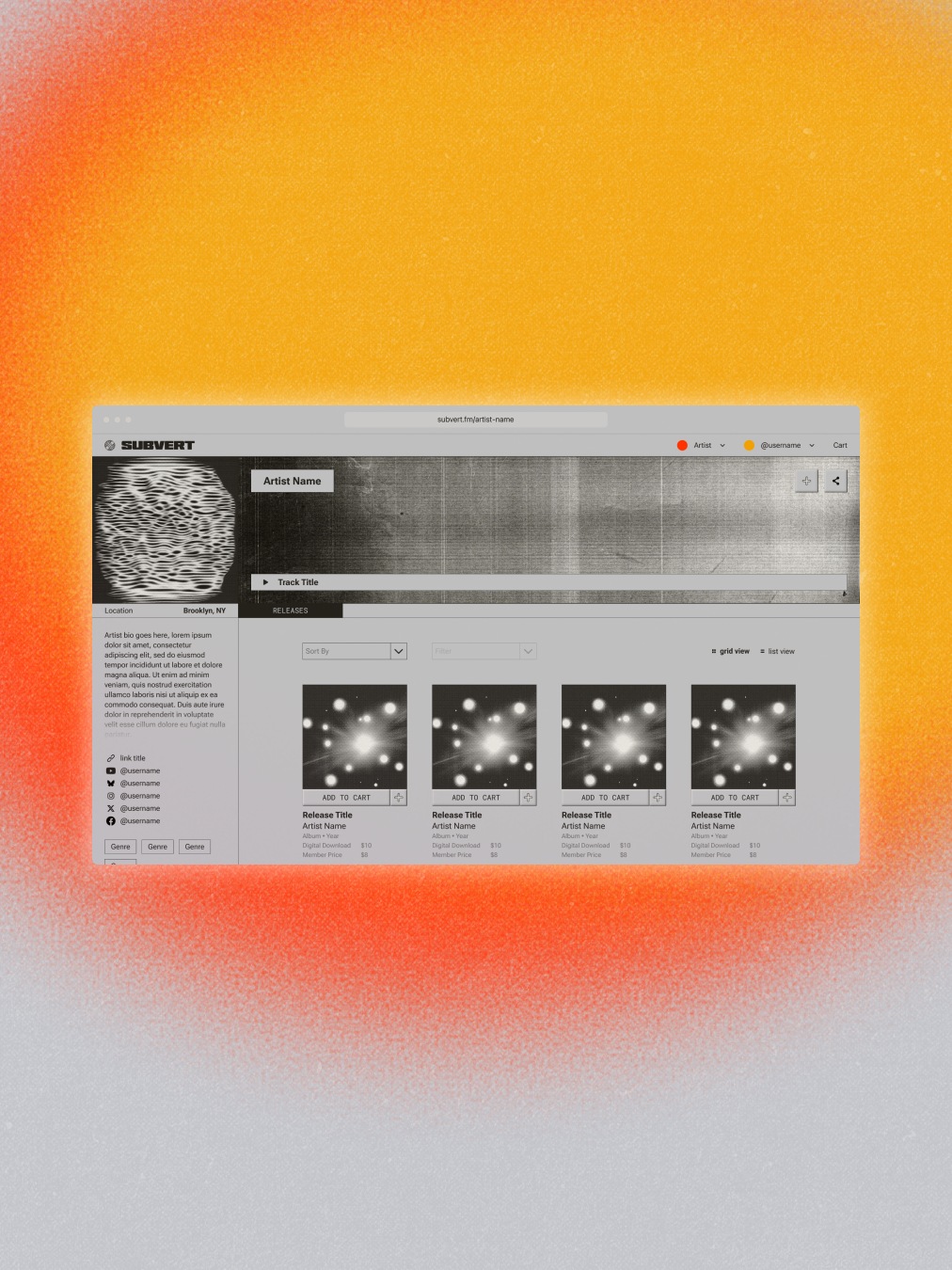

What makes Subvert different is its model, detailed in its digital zine “Plans for an Artist-Owned Internet.” Initially announced in July 2024, Subvert.FM bills itself as a music marketplace collectively owned by musicians, labels, and individual supporters who purchase memberships. It believes in democratic governance rather than a traditional corporate structure, in financial transparency over secret dealings, and in a future directed by its members rather than the whims of investors or capital.

A physical copy of Subvert’s zine “Plans for an Artist Owned Internet”

Ambitious? Sure. But more than ever the internet needs new futures immune to “enshittification.” That term, coined by Cory Doctorow describes the phenomenon of internet platforms degrading their services to maximize profits — think Google’s transformation from preeminent search engine to moronic A.I. mouthpiece, or Elon Musk’s alt-right razing of Twitter (enshittingly retitled to “X.”) Over a video call, Subvert founder Austin Robey says the sale of Bandcamp was always the most likely outcome.

“It shows the natural result of platform capitalism, no matter how you package it.” Robey says. “We really need to dream up new systems beyond this version that keeps betraying and exploiting users over and over again.”

Subvert’s owners include over 8,500 musicians and 1,500 labels like Warp, Polyvinyl, and Thrill Jockey; an alpha launch for members is scheduled for late October. If you’re not an artist or label and want to have a vote in Subvert’s direction, you can purchase a membership for $100 (a membership is not required to buy music on Subvert). Memberships aren’t ceremonial, either: In the last few months, Subvert’s Board of Directors (elected by its members) voted for 0% platform fees, opting instead for a GoFundMe-inspired tip model to help sustain the site.

Robey says the energy his felt from Subvert’s in-person meet ups feels different than that of previous cooperative platforms he’s tried to launch. “It was a little too early for some of these ideas,” he says. “It feels like the time actually is now. There’s a real awareness of an underlying problem that we’re trying to solve.” It’s this hunger for change that, despite the scope of the challenge, energizes him throughout our conversation.

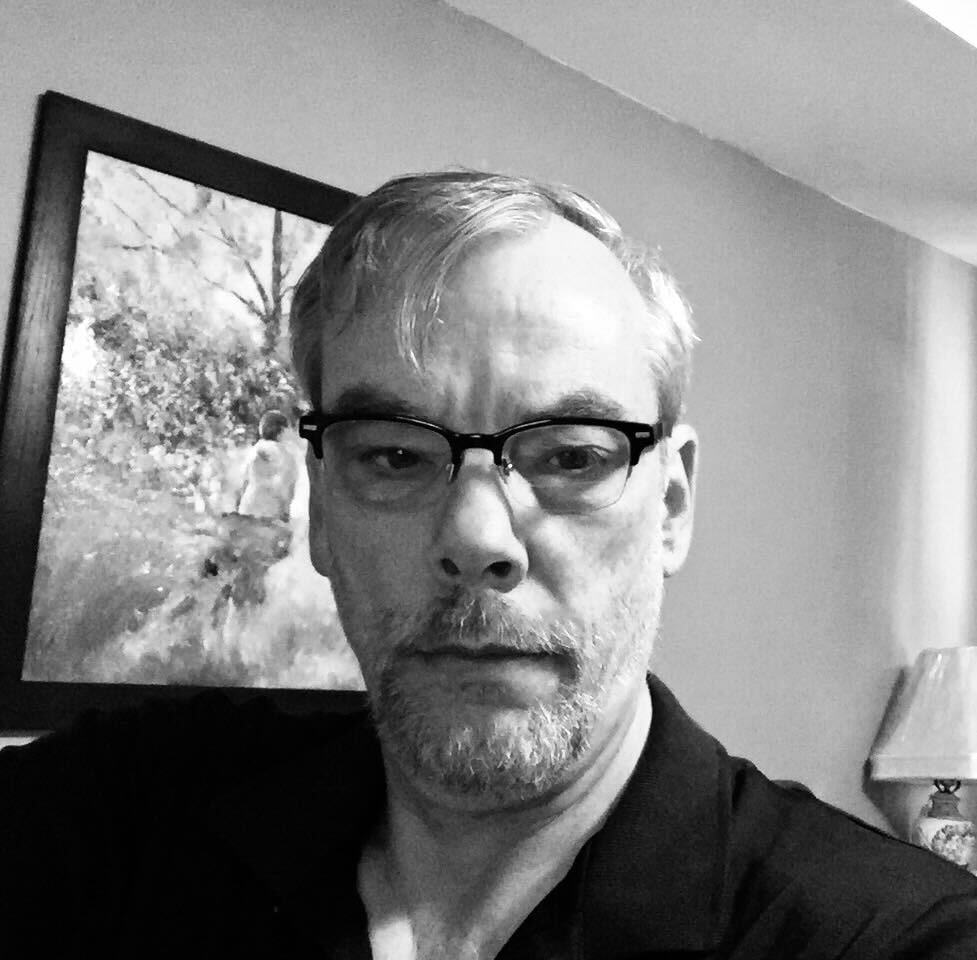

Austin Robey at MUTEK Forum. Photo by Maryse Boyce

The FADER: You’ve worked on co-op platforms before. What are you bringing from those experiences to Subvert?

Austin Robey: I was part of a team that developed a project called Ampled. It was effectively a Patreon for music. But ultimately, through lack of funding and burnout, it wasn’t responsible to continue.

I think there are many things to take away from that. One, the Patreon model for music has revealed itself to not be a natural fit, in my opinion. And I really wanted Subvert to start from the place of it not being a volunteer project. The idea was, how can we start a cooperative and make sure that it is resourced to be actually competitive?

Many of our previous challenges were downstream of lack of resources. I fully believe in cooperatives, worker-owned firms, as a successful and demonstrated alternative to capitalism. But to me, what’s actually the most important is less worker precarity, better worker security and pay. And so I’d say that of the many lessons, one of the primary ones was that there’s a deep importance to making sure that we are able to properly resource this so that it can serve the needs of both workers and artists alike.

Let’s turn this cooperative into a container where we can own every stat of what touches independent music and create a totally alternative economy that is fully worker and artist owned.

How has that journey been? I noticed in your zine there’s mentions of the need to attract investors. Does that fit within the cooperative philosophy, or is there friction?

Talk to any cooperative operator and they’ll tell you that the enemy is not funding. It’s in the details of how it’s done. And for us, that has been a long, transparent process, fully turned inside out where members have been able to provide feedback on everything from the start.

[Subvert has] a unique legal structure. We have a cooperative and a public benefit corporation, two entities working together. The co-op owns this corporation [and] investors are able to invest in that public benefit corporation. [That’s] a recognition of the limitations of both of these corporate forms on their own, and we’re seeking to mitigate those limitations, but also harness what is uniquely strong about each of them.

For co-ops, that’s full member control on a one-member, one-vote basis. The platform and platform operations are all governed as a cooperative. And then the public benefit corporation allows the co-op to raise funding in ways that we can attract sufficient capital. If there were a network of capital providers that specifically were interested in funding cooperative enterprises, then that would be our first choice. But we’re kind of forced to innovate here.

When it comes to building something like this and putting it out into the world, a lot of the questions boil down to what compromises are palatable for us and what are we not willing to compromise on. And so for us, [we’re] not willing to compromise on cooperative control of Subvert. There will never be a time where investors can override the will of the cooperative. But we also want to properly pay workers.

It’s a delicate balance. One of the toughest problems that we are solving at Subvert is how to thread this balance, where the relationship of capital to an organization has created a lot of dissonance and inconsistent corporate messaging.

In your zine you say your biggest adversary is cynicism. What’s your plan for reaching people who are understandably skeptical that the internet can produce anything of value?

Well, we have to earn trust. It’s about actions more than words. The smart thing to do is to be cynical. You’re less likely to look dumb when you just reflexively dismiss something. But I’m so encouraged by how many people have rejected that cynicism and said, “I believe that this is possible and I want to be a part of it.”

But I would also embrace skepticism. That’s a good thing. People should be skeptical of the model and really look into it and understand it. People should be skeptical of me. The lesson is to not place blind faith in people and good intentions. We have to build real systems of accountability. And so in many ways, a skepticism towards Bandcamp in 2020 and 2021 and pressure applied to put artists on the board or have some kind of community accountability agreements would have done way more than all of the protests against Spotify.

Skepticism and pressure is often to protect something that you love. Ask the Bandcamp workers why they unionized. It wasn’t because they hated the company. It’s because they love the company. And so that kind of skepticism should be in place. We have to be a functioning democracy.

So much of the user experience in today’s Internet is built around getting people addicted. people addicted and, you know, boost like boosting their fight or flight through different means. Even just from a design perspective, it sounds like you might have to approach this from a different way.

It will largely feel familiar as an experience to people, but some things are different. For instance, the platform knows whether you’re a co-op member or not, [so] your experience will be different: having an ownership dashboard, having access to financial information. It is going to be an experiment that feels very vulnerable for the team at times, but I’m hoping that it really begins to prompt people to ask questions that we haven’t been asking before. Who owns it?

Apply that question to any project in any creative industry, any company. The answer is you probably don’t know and you can’t find out, but people are asking that question now about boiler room, sonar. People are asking that question about Bandcamp. I really hope that we just start to think a little bit more critically about that.

Your zine’s title suggests that the Subvert model could be the foundation for something outside of itself.

We want to encourage more collective ownership and control. We want to see successful cooperative models proliferate. I think the primary product of Subvert is the co-op. It’s not the platform.

The platform is a way to generate membership in a global, self-governing legal entity that owns a platform but can own other things too. Like, this is like our outline for what a Mondragon [the world’s largest worker cooperative] of music could look like.

Let’s talk about how a global cooperative can own buildings. Let’s talk about housing cooperatives. Let’s talk about acquiring other businesses. Let’s turn this cooperative into a container where we can own every stat of what touches independent music and create a totally alternative economy that is fully worker and artist owned. That’s the big vision.