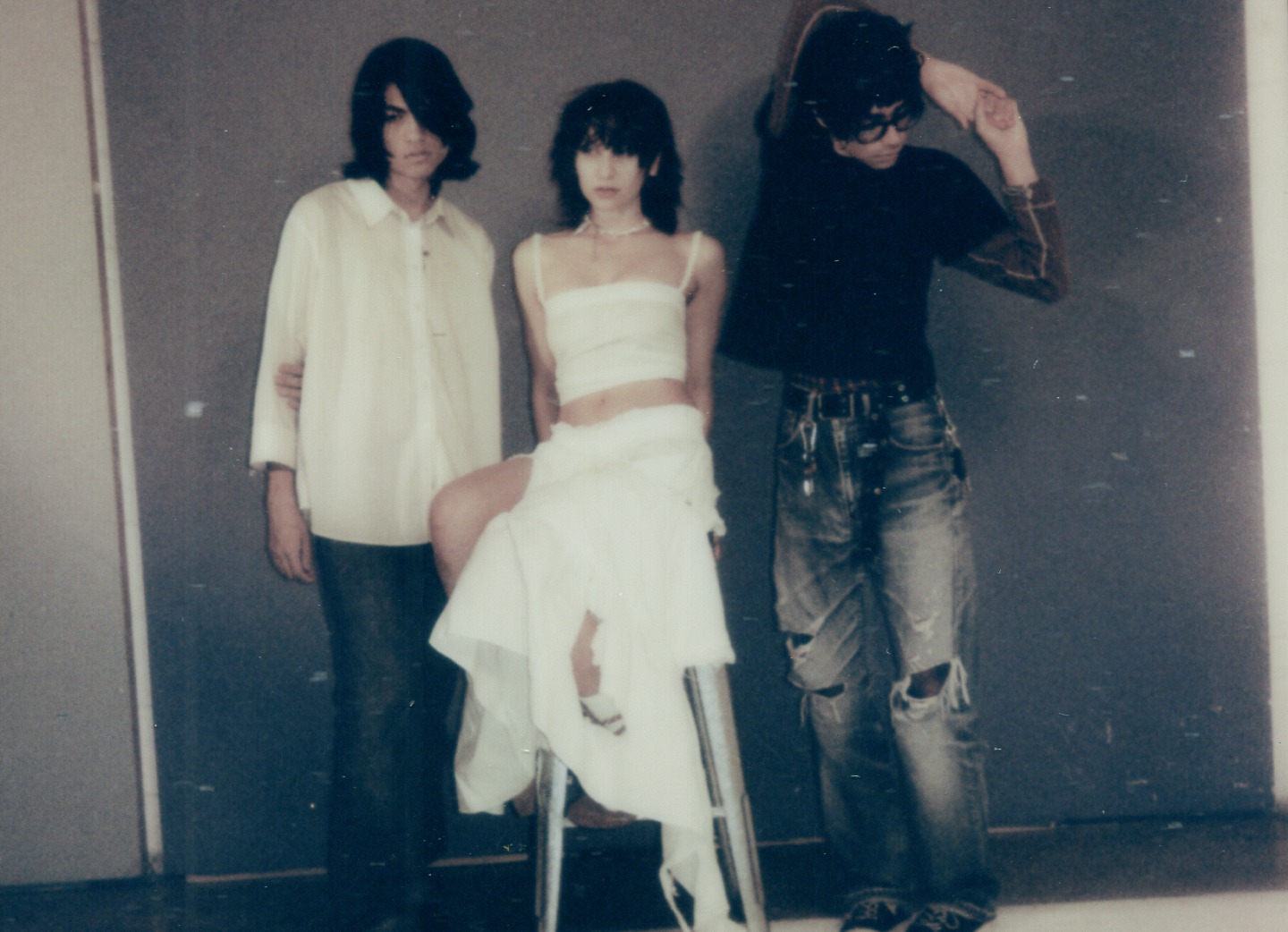

julie

Silken Weinberg

The FADER’s longstanding GEN F series profiles the emerging artists you need to know right now.

Keyan Pourzand and drummer Dillon Lee were reluctant to take center stage even after they started julie. They were shy music obsessives studying at El Toro High School in Lake Forest, Orange County, united by a love of Sonic Youth and The Breeders, as well as an urge to make something of their own. “I knew I wanted to sing,” Pourzand says over a video call, his head popping up between his bandmates as they gather around the laptop, “but I didn’t have the guts.” Enter Alexandria Elizabeth, a cool friend of a friend who loved Daydream Nation as much as they did. One DM to Elizabeth and the trio was complete.

Right from the start, julie’s wall of sound aesthetic was a smokescreen; something to shroud the rock trio’s self-doubt and emotional turmoil from prying eyes. “flutter,” julie’s debut single released in 2020, sprints through gothic melodrama and brooding teenage angst. “I’m draped in lead and heavy as a slug / Drag the body under the rug,” guitarist Pourzand sings through clanging riffs and a thicket of noise that sounds like a helicopter taking flight. The song, released just a month into the pandemic, caught a wave and has been streamed over 30 million times, far surpassing the band’s expectations.

“flutter” was only ever intended to be a flare in the night sky, something the band threw up to see who was paying attention. Its massive success left the band in a quandary. Pourzand and Elizabeth had both enrolled at the Southern California Institute for Architecture with Lee joining them in the move to Los Angeles. When the band first started, julie would travel from Orange County to L.A., watching local bands Momma and Cryogeyser and shopping at Amoeba Records. They assumed the move would be a slipstream into sharing stages and filling those shelves with their own music, but soon realized that studying to be architects and being in a band don’t mix.

“For a long time, maybe a year and a half, we felt like we could do both,” Pourzand says. “Like, ‘This is fine. I just need to stay up longer and drink more coffee and have more energy drinks and we can make it happen.’” In December of 2022, wired from a mixture of caffeine and an Atlantic Records deal that makes Turnstile and 100 gecs label mates, Pourzand and Elizabeth attended their final classes before dropping out.

The streaming success of “flutter” is a significant chapter in the shoegaze revival. The song appeared on prominent Spotify playlists and has taken off on TikTok with a young audience fascinated by the intensely loud and reverb-heavy sound. The resurgence has encompassed the original 1980s bands as well as modern artists such as Wisp and flyingfish, who also have songs with tens of millions of streams. Though all three members of julie are avid My Bloody Valentine fans, they were adamant that my anti-aircraft friend, the album they have spent the past two years writing, would not be fodder for nostalgic rock music fans.

“It feels a little bit like a burden at this point,” Pourzand says of the shoegazer tag. “I’m not mad, because people are listening to our music, but that term makes us feel pigeonholed. People start to get expectations of what you should sound like and that is limiting.” Elizabeth is more forthright about the whole thing. “I just feel bored,” she says. “I’m just like, can we have a new word?”

my anti-aircraft friend stands on its own two feet as an album steeped in indie rock classics and lyrically occupied with concerns of mental well-being and establishing identity. “Catalogue” thrashes and squalls but at its center is numb with Elizabeth singing “I don’t feel sexy / I don’t feel amused / But I will try to undress you / Tethered to the wall” as the noise rises and smothers her. The experimental post-hardcore powder keg created by cult group Unwound was a major influence on the album and can be heard in the chugging roar of “Very Little Effort,” as well as the tightly-coiled tension of “Tenebrist.”

Silken Weinberg

Free from the pressures of education and distancing themselves from any outside expectations, julie focused on writing their album as directly as possible without worrying where that process would take them. Still, they readily admit finishing the album took them “to hell and back.” Perfectionism played a role, as well as their insistence on creating all of the artwork that goes with it. But also because all three of them are going through a period of establishment: of julie as a band in a crowded industry, and of themselves individually, as new adults in a wounded world.

Pourzand confesses that a lot of the songs are centered around the end of an “unhealthy bond with someone,” the kind of deep connection that can go from tight to restrictive in a short time. In “Clairbourne Practice,” julie weave a wounded portrait of two people trying and failing to make one another happy. Grasping for answers, Elizabeth can only fall back on cutting her hair differently. Similarly, “Feminine Adornments” is a grungey lament of her people-pleasing tendencies and the serenity that comes with letting go.

Silken Weinberg

“We’re all 22 and 23 right now,” she says. “And going through this stage of your life, you’re going to grapple with confidence and struggling with self-doubt. When I wrote the lyrics for ‘feminine adornments,’ I wanted something powerful for people to sing along to. It’s this moment where I finally believe in myself and I’m doing what I can to take care of myself. But then you still have those moments of doubt when you’re trying to trust yourself to make the right decision.”

Asked for words other than shoegaze that they’d rather hear about my anti-aircraft friend, the band reach for terms like “beauty,” “melancholy,” and “destruction.” “I have really big feelings,” Pourzand says, “and being in a band where you can mess with tones and push amps to make whole new textures, really fucking destroy things without any consequences, is the biggest release. You get to free yourself from these pent-up emotions in a way that’s healthy.” They point to Lee’s album artwork, an illustration of a black-and-white woman with her back turned, meekly playing guitar in front of an amplifier erupting with color. Don’t look at me, the figure says, listen to the noise I’m making.