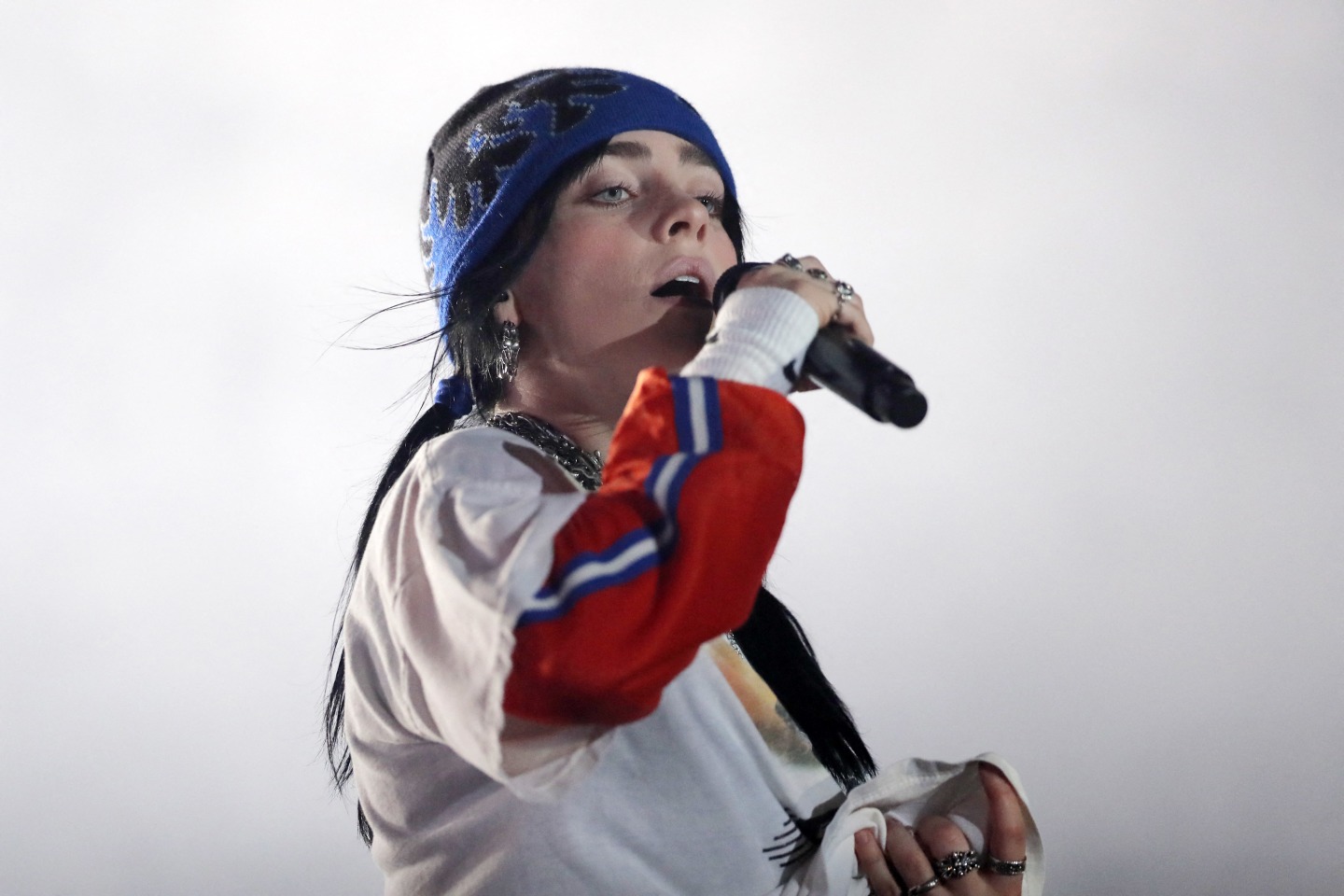

Nik Freitas

There are two ways to look at games of chance, both of which are naive in their own way. The first is completely innocent, fueled by the optimism that comes with feeling lucky; the second is a desperate hope, based on the false assumption that a certain outcome becomes more likely if it has occurred less than expected. The latter is the “gambler’s fallacy,” the unrealistic belief that everything in life must be fair and fifty-fifty, that balance and equality are universal and, therefore, the scales will eventually tip in your favor.

The next time Bright Eyes blow on their dice, say a prayer, and hope for Five Dice, All Threes, there’s a 1 out of 7,776 chance it’ll hit. But judging from the way Conor Oberst talks about the likelihood of satisfying critics and fans with their tenth studio album, it’s abundantly clear that he’s never been playing the same game as everyone else. He’s been “making shit that upsets everyone” for the last couple of decades, after all, and it’s not like he’s hoping it’ll change now.

“But it’s kind of a badge of honor,” the 44-year-old says with a rueful smile. “I don’t say this very often, but I am proud of my band for always making different shit, when some bands find a formula and just roll with it.”

It’s a humdrum L.A. afternoon, and we’re drinking hard kombuchas on the porch of Oberst’s house. Hidden behind a deep thicket of towering oak, palm, and eucalyptus trees, we’re shielded from the smog-orange sun and the chaos of a city where it’s always rush hour. The only smoke is coming from our cigarettes, which quickly accumulate in a sizable glass ashtray. Oberst, however, always makes sure to have a stockpile of slow-burning American Spirit handy. His willingness to share an entire stack of bright yellow boxes, three packs wide and five packs tall, feels like Midwestern hospitality at its finest.

“Don’t get me wrong, it’s great to sell records, and it’s great to make money, but that’s truly not why we do it,” the Omaha native says on behalf of himself and longtime bandmates Mike Mogis and Nate Walcott.

“We probably lost a lot of opportunities to be more rich or more famous, but I don’t regret it,” he adds. Oberst grabs a fresh pack of cigarettes from the pile before stating that he sees Bright Eyes as “just a cool band that makes cool, weird shit.”

“And some people get it, some people don’t,” he continues over the crinkle of torn cellophane, “but I can’t spend my time thinking about how to please people.”

Their new album, Five Dice, All Threes, is “straightforward,” with simpler instrumentation and big hooks that “make it feel like it’s kind of fun.” It’s the stuff he liked listening to as a teenager, when he was making his own music in the basement with his dad’s reel-to-reel tape recorder. The songs are “short and catchy, at least by our standards,” he says, name-checking The Replacements as a big inspiration.

“And there’s not…” Oberst catches himself mid-sentence. “Well, there’s a little bit but, I guess, it’s not as fucking psychotic as our other records.”

In many ways, it’s the complete opposite of Bright Eyes’ last release, Down in the Weeds, Where the World Once Was, a sweeping orchestral production that marked the end of the band’s nine-year hiatus in 2020. A grandiose, almost cinematic record with well-rounded instrumentation and thoughtful arrangements, Oberst rolls his eyes while describing the “giant 14-piece band that took three buses and a fucking semi-truck” to tour. It was a complicated setup, he says, before joking that while Down in the Weeds was a democracy, Five Dice is an Oberst-run autocracy.

Oberst didn’t have any actual plans to record a new record until The So So Glos’ Alex Orange Drink stayed at his house last winter. While the D.I.Y. punk stalwart was there, the old friends would spend hours playing informal jam sessions with their guitars on his porch, where the two wrote what would eventually become Five Dice, All Threes’ first two singles, “Rainbow Overpass” and “Bells & Whistles.”

Five months and many trips to Omaha later, the self-produced Five Dice, All Threes was completed in Mogis’ studio with the help of Orange Drink, who co-wrote and provided vocals for seven of the album’s 13 tracks. Oberst is all smiles while praising Orange Drink’s ability to create undeniably catchy hooks and melodies out of simple chords. It’s a talent he says solidifies The So So Glos frontman’s place “in sort of a lineage of cool shit,” who can write scrappy tracks that channel the energy of a snotty Stiv Bators or a Sorry Ma basement cut.

“We’ve been doing it the same way since we were fucking kids,” he says while lighting another cigarette. He smirks, “We just don’t listen to anybody.”

Oberst isn’t fronting when he says that either. Between “Bells & Whistles’” sunny melody and the gritty garage punk energy of “Rainbow Overpass,” Five Dice is a record propelled by energy, nostalgia, and texture. It features Cat Power’s soulful voice on the jazz-inflected “All Threes” and The National’s Matt Berninger, whose well-known baritone becomes unrecognizable after being rewound, warped, and slowed down on “The Time I Have Left.” For the most part, though, Mogis keeps the production tricks to a minimum, with Oberst explaining that the band wanted to keep it as close to a live recording as possible. Akin the early days, when he was still the “boy in a basement with a four-track machine / Who’s been strumming and screaming all night down there” from Letting Off the Happiness.

Five Dice, All Threes comes off like an homage to some of Bright Eyes’ earliest recordings. It’s a raw, unpolished D.I.Y. record that’s best enjoyed through the tinny speakers of a cheap record player, with an honesty enhanced by the artifacts an expensive sound system would scrub away. It’s simple and unpretentious, gruff and rough around the edges, but its imperfections make it feel like a more intimate experience. It’s a record stripped of any overcomplicated language or flourish, leaving behind just the simple, barefaced truth.

Nik Freitas

There’s something very earnest and unburdened about the way Oberst recalls his first few years of high school, when he started to hang around his older brother Justin’s upstart indie label, Saddle Creek Records. He’d just started high school and didn’t have a driver’s license, but he’d already released his own tape and was starting projects with friends like Todd Fink of The Faintand Cursive’s Tim Kasher, who was the co-founder of Oberst’s fairly successful punk band, Commander Venus.

In the background of all this was Bright Eyes, an eclectic and unvarnished solo project where Oberst freely experimented with sound collage, pop-adjacent songwriting, and pensive lyricism, often letting his voice strain beneath the weight of its own emotion. The stakes were low, and he wasn’t at the point where most people were betting on him. Instead, the people around him still treated music as a means of expression — an act of messy experimentation coming out of the basements of Omaha in the early ’90s.

The year after Commander Venus broke up, a 15-year-old Oberst released his first Bright Eyes album, A Collection of Songs Written Between 1995-1997, an unrefined, Mogis-produced bundle of 20 songs spanning genres, moods, and feels. Against the crackly, bedroom production, there’s the intense strumming and promising songwriting of “The Awful Sweetness of Escaping Sweat,” the chaos of chimes and a D.I.Y. drumstick countdown on “I Watched You Taking Off,” and the long-forgotten movie he recorded on a dictaphone for “Driving Fast Through a Big City at Night.”

A Collection of Songs caught the attention of the Elephant 6 collective in Athens, Georgia, where bands like The Olivia Tremor Control, of Montreal, and Neutral Milk Hotel were creating anti-corporate pop using sound collaging and tape manipulations. In 1999, Bright Eyes released Letting Off the Happiness, which was one of the last times Oberst would play with a straight-up D.I.Y. punk aesthetic outside of his Desaparecidos side project. If you listen carefully, songs like “The City Has Sex” shares a similar aesthetic and attitude with “Rainbow Overpass” — punchy, existential, and honest.

Most Bright Eyes fans typically enter their most beloved era with a holy trinity of records that remain cult favorites to this day. In 2000, the band debuted their third studio record, Fevers and Mirrors, the first of three albums that would set a certain musical expectation among fans. Bright Eyes and Conor Oberst started to become synonyms for melancholic Americana indie folk, a connection that only continued to solidify with 2002’s Lifted or The Story Is in the Soil, Keep Your Ear to the Ground — and culminated in 2005’s I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning and its breakout hit, “First Day of My Life,” a love song that’s been covered by Mac Miller, interpolated by Young Thug, and co-opted by wedding planners around the country.

“Every quote-unquote hit, or song, or anything that’s ever been attractive to the mainstream amount of people has been just a complete fluke…,” Oberst trails off, just shy of name-checking the track.

His face is hard to read in that moment, but from other parts of our conversation, he clearly has mixed feelings about a song that may have “made us so much fucking money, and, realistically, fame,” but has also arguably overshadowed the rest of his career.

At last, Oberst finally appears to settle on an expression of irked disgust. To even briefly entertain the idea of having “to make a fucking quote-unquote Americana record for the rest of our fucking lives” makes him look unfathomably miserable. Or perhaps it’s being constantly reminded of this bizarre mass misunderstanding of what his band actually is; how mystifying it is to know that people’s perception of Bright Eyes is based on a song that’s probably the least representative of their actual body of work, because “our band is like way more fucked up and weird than that.”

“And if anybody actually listens to our catalog…,” Oberst stops again to let out a frustrated sigh, “they’ll know that immediately.”

After the release of I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning, Oberst learned the hard way that nothing would satisfy his fans or critics, even Digital Ash in a Digital Urn, the catchy, synth and sample-filled record released on the same day. Following this was Bright Eyes’ acclaimed live album Motion Sickness and then Noise Floor (Rarities: 1998-2005). Despite both acting as showcases of some of his most visceral songwriting — most notably the helpless devastation of “Amy in the White Coat” — and the latter being modeled after Oberst’s first release, both were met with little fanfare.

In Oberst’s case, he talks about just wanting “to put this thing out into the world,” and then seeing that “the world doesn’t even understand it or care about it, and this has happened to me multiple times.”

“And five years later, all of a sudden people are like, ‘Oh, my God, that was such an amazing album,’ and it’s just like, ‘Yeah, but where were you when the album came out?’” He lights another cigarette, takes a deep drag, and slowly exhales a plume of hot white smoke. “Because it seemed like there was no one fucking there. It seemed like no one cared.”

At this point, I feel like I have to directly ask whether the negativity played a role in wanting to step away for a second. He starts and stops his answer a few times, trying to think of how to phrase his response before saying, “Yeah, but I got…” Again, he trails off, taking a moment to think.

“I was already doing solo stuff, but I kind of got to a point where I was — and I hate to even use this word because it’s so fucking stupid — but there was such a brand of what ‘Bright Eyes’ was meant to be,” Oberst says. “It wasn’t so much that I wanted to get away from Mike and Nate, it’s just like I wanted to get away from myself. I wanted to get away from Bright Eyes. I wanted to get away from the band and do my own shit.”

There’s arguably some truth in what he’s saying. After all, his solo releases like Ruminations were met with excitement and still routinely praised, as are several songs from his other band, Conor Oberst and the Mystic Valley Band, and his past project with Phoebe Bridgers, Better Oblivion Community Center.

He takes a deep breath. “So I did that for a long time, and then, at some point, it felt right to come back, because they’re some of my best friends. So it’s like, ‘Okay, let’s do this again.’”

Then came the years of open disparagement from fans, who would begrudgingly listen and uniformly criticize 2007’s Cassadaga — named after a town of psychics in Florida — with a catchy, rollicking Americana single called “Four Winds,” and a set of dreamy, starry-eyed songs that started a major shift in opinion. Four years down the road, Bright Eyes would release one more album before their nine-year silence, 2011’s The People’s Key, a warm, spiritual record that was panned by a now-hardcore fanbase upon its release.

Bright Eyes fans have a habit of refusing to acknowledge any newer albums that diverge from this perception, so much so that there’s “a running joke” between Oberst and his longtime bandmates Walcott and Mogis that “every time we put out a record, everyone’s gonna hate this and, in five years, these people come up and say they love that record.”

“It’s like a delayed effect, and it’s like, ‘Well, I kind of wish you would have felt that way when we made the actual record,’” Oberst says after I bring up a recent Reddit poll that named 2011’s The People’s Key the “most underrated” Bright Eyes album. He seems genuinely surprised, recalling how much “people fucking hated that record,” even though he thought “people were going to be stoked” that they were making a record that “was going to be like The Killers or The Beatles.”

“I was like, ‘Wow, we just did it, and no one gave a shit. Like, no one fucking cared. No one bought it,’” Oberst says. “I mean, people come to the shows because, like, they want to hear our old songs. So we don’t have problems selling tickets, but records, we definitely have problems.”

Oberst tries to keep a straight face but seems a little despondent, recalling the disappointing and, frankly, disturbingly vitriolic reception to their work after I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning. Despite famously singing that “I do not read the reviews / No I am not singing for you” on Lifted’s final track, “Let’s Not Shit Ourselves,” there’s always a point of critical mass where it does start to take a deep emotional toll.

Still, the response to the first two Five Dice, All Threes singles were far from positive in some quarters. On the dedicated Bright Eyes subreddit, a vocal faction of listeners directed an alarming amount of vitriol towards Orange Drink in the lead-up to the release. While most fans have come around to the fact that a lot of Bright Eyes can only be belatedly appreciated, Five Dice, All Threes was still prematurely criticized as “cheesy” and a “regression,” with one particularly egregious concern troll selfishly fretting, “I do worry that there’s a certain level of pain Conor doesn’t want to access anymore.” But for Oberst, the worst has been the unfair claims leveled against Orange Drink, who’s been accused of influencing him into recording a “cheaply inspired” album with “some mid-punk dude,” “riding on CO’s coattails and infiltrating the band.”

Hearing this, Oberst begins to get emotional. He’s understandably furious and deeply upset, underscoring the fact that Orange Drink was “right there” with him. He’s the “beautiful kind soul” at the heart of Five Dice, All Threes, the one who was always encouraging Oberst “to finish this song.”

“The only reason this record even exists is because, in some crazy coincidence, he ended up staying here, and we ended up writing these songs,” he says, “and then I was like, ‘Oh, I can write songs again.’”

His eyes begin to well up. “They’ll never know him, but he’s like such a kind, beautiful soul like…”

Oberst is visibly confused, hurt, and angry. He leans towards my iPhone, which has been recording our conversation, and raises his voice to address the commenters, “Go fucking listen to Blowout, one of the best records ever fucking made. They’re like America’s fucking answer to the fucking Clash.”

“And if you don’t know who The Clash is, then fuck you.”

Nik Freitas

Nostalgia is a powerful drug, and Oberst has always been able to speak to the complex feelings of bitterness and alienation inherent to adolescence. Even at its darkest, the past holds a strange comfort, which you can feel within his descriptions of the most mundane and ordinary of experiences. Everyone has a memory of a whining refrigerator, looking down at their shoes, or sitting alone in a diner, and an understanding Oberst is able to take you there. You aren’t alone in feeling these ugly and messy emotions, but you have to face them in the hopes that you’ll eventually be able to let them go.

To this day, he has the rare gift of being able to write lyrics that can grow alongside you. Even after decades of listening, I can still find something incredibly personal and profound in even his oldest work. Whether it’s some alternate interpretation of a metaphor or a more mature perspective on a turn of phrase, there’s always an unrealized truth or tidbit of unexpected wisdom.

He still has an uncanny talent for accurately describing the human condition while remaining grounded in reality, which would make anyone inherently pessimistic. But these moments also appear to be coming from a willingness to evolve and grow; to be honest and open and free; to not spend too much time chasing a temporary dream when the answer may be right in front of you.

When I tell him why I connect to his songwriting, Oberst does the “aw shucks” routine and tells me I’m “just buttering his bread.” But I stand by what I say, telling him that I’ve followed Bright Eyes as they’ve grown and evolved over time and have a particular soft spot for those first two releases; that I appreciate Five Dice, All Threes for its ability to help me revisit my own angry and selfishly naive past from a more mature perspective. There are moments on the album that exude pettiness, resentment, and contain the kind of blatant “fuck yous” that will undoubtedly cause a stir. But in a world where “authenticity” is considered cultural currency and the commodification of vulnerability has become trendy, Oberst is ready to do something else: whatever he wants to do.

At 44, Oberst seems to have less patience for self-pity and morbid songs that straddle the line between shattering and shocking, especially when he’s refined his songwriting into something even more universal and resonant through the use of fewer words and more direct storytelling. In some ways, Five Dice, All Threes feels like a moment of catharsis and revelation, where Oberst realizes that shit’s unfair and sometimes we get fucked over, but we all eventually end up in the same places and positions. And sometimes, it takes some reflection upon those formative years, the ones where you were slowly crafting your identity for the first time and, now, having a second chance to fix those accidental flaws by giving your younger self the advice you’ve accumulated from experience.

We all share the same predetermined fate, and it’s not about playing games, house advantages, and shallow hopes. As a realist, Oberst has learned it’s all rigged, that luck is an illusion, money isn’t real, and all we can do is be kind to each other during the ride. Because by the time you do manage to hit that improbable Five Dice, All Threes, you’ll realize you’ve missed out on the actual things that make life worth living: true love and pure happiness.

Oberst has been nothing but warm, honest, and funny this entire time. He unironically stans reggae rockers and fellow Omahans 311, makes fun of his 2004 cover for The FADER, and doesn’t care for the internet, to the point where I have to ruin his day by informing him of Andrew Tate’s existence. And he’s the first to make a self-deprecating joke about his “irrelevance” or just white guys in general (“There’s a lot to make fun of in that department”).

But what’s surreal is that he’s just as interested in my story as I am in his. The moment that’s stayed on the front of my mind since our talk on the porch was the way he halts the conversation after I make a glib remark about finally being in love.

“Why would you say that?” Oberst says. He’s looking me dead in the eye, not with judgment, but genuine confusion. “I mean, would you describe yourself as happy right now?”

“I think being happy is something to celebrate and being with a person that loves you, that makes you feel good, and safe, and taken care of, is the best thing ever,” Oberst says.

I think he realizes I’m deflecting, too embarrassed to say something that’ll make me seem vulnerable or corny. Oberst looks a little sad but doesn’t press.

“Don’t shit on your own happiness,” he says. “Real love is rare.”