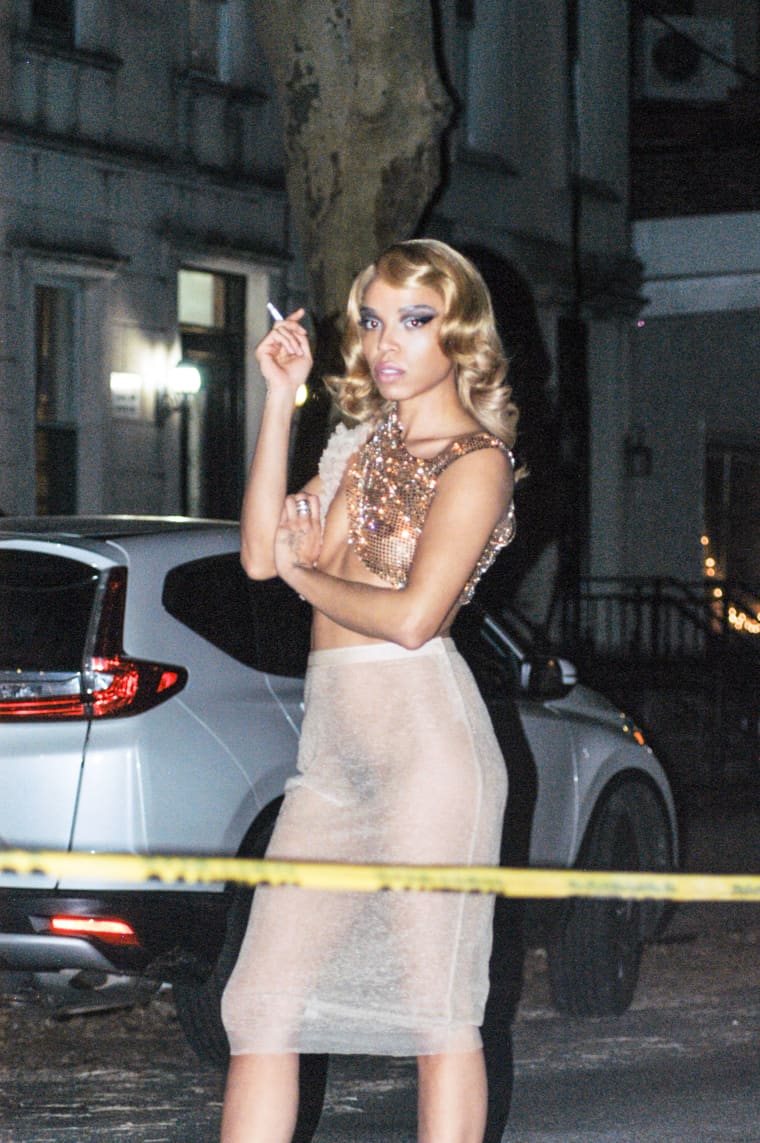

“I was a really shy kid, but the people who knew me knew I wasn’t really shy,” Zsela tells me from across a coffee table on the final day of May. She’s just arrived at The FADER office, decked out in denim, hair in long, golden braids. She seems relaxed, considering her debut album is due out two weeks later.

In the context of current industry pressures, Zsela (29) has been relatively slow to arrive at her first full-length. Big For You comes five years after her debut single, “Noise,” and four years after her debut EP, Ache of Victory. Aside from that project’s 2021 remix tape, she’s been quiet in the interim. Her meticulousness betrays a note of perfectionism, but not the type of anxiety-riddled nitpickery the term connotes. “It took the time it took,” she says, “and I’m glad, because where we landed with everything feels like the best version.”

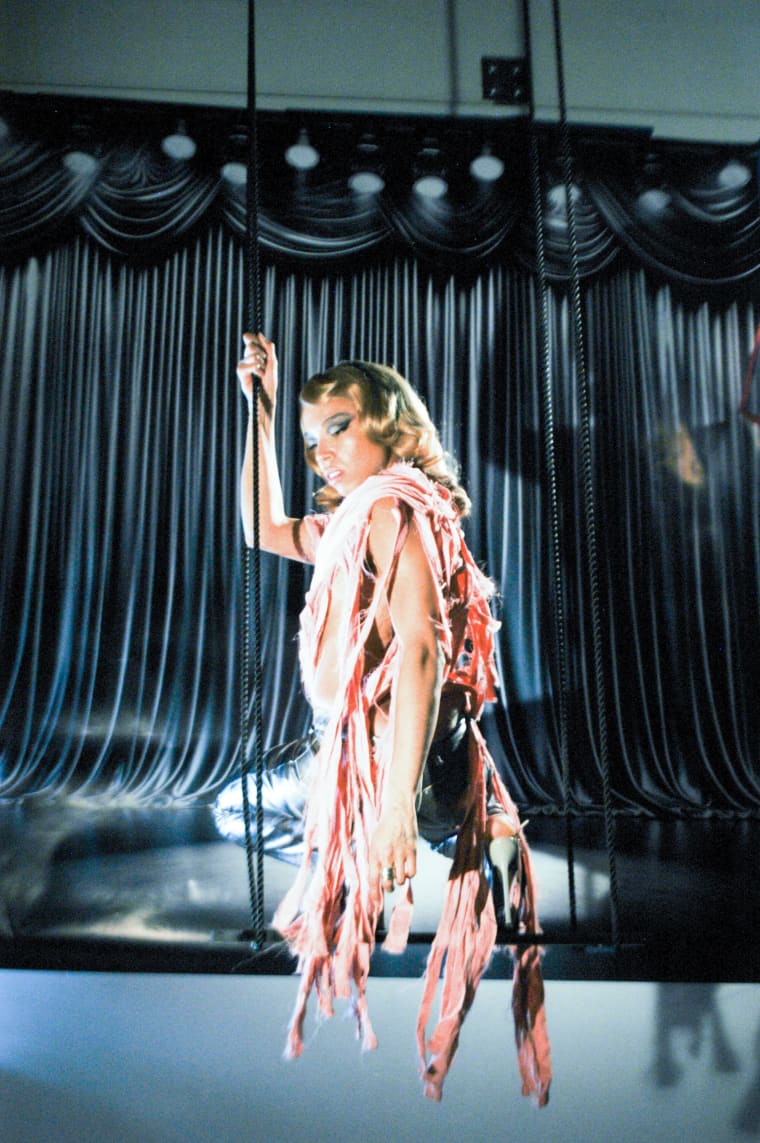

Zsela’s unhurried approach pays dividends on the new album, a diverse yet cohesive set of 10 tracks, peppered with moments of bona fide brilliance. The first of these instances comes on the record’s second track, “Fire Escape,” when Zsela sings “I’m falling down” for the first time, and an initially playful instrumental is replaced by an astonishing wall of sound. Other coups de grace are subtler, less cathartic but no less genius, products of Zsela’s mind meld with superproducer Daniel Aged (Frank Ocean, FKA twigs, Kelela, Rosalía, et al.), a collaborator on every song in her catalog.

Several of the album’s standouts benefit from stellar supporting casts: Nick Hakim and June McDoom’s singular vocal stylings sit next to Zsela’s venomous relationship revelations on “Brand New,” with more special sauce applied by guitar legend Marc Ribot, who also contributes an iconic lick to accompany the haunting spoken-word poetry of “Easy St,” one of several songs to feature inspired additional production from Jasper Marsalis (aka Slauson Malone 1), another of which — penultimate track “Moth Dance” — is the seed from which the rest of the record germinated.

Ache of Victory, as the latter half of the EP’s title implies, was a triumph in its own right, the project that gave Zsela the confidence to overcome her shyness and wield the full power of her voice. On Big For You, she left her comfort zone once more, this time mastering the art of listening as she made space for others to help mold her sound into shapes she hadn’t yet imagined.

The FADER: I saw a video where you said the earliest songs you wrote as a kid came from dreams. Tell me more about that.

Zsela: That’s one way I would write when I was younger. I’ve been writing songs since I was a kid, but I was very private about them. They’d be these improv songs that I’d sing into a tape recorder — meandering, seven-minute songs — and play for my parents. It was insular like that for a long time, and I’m still trying to understand what that was about.

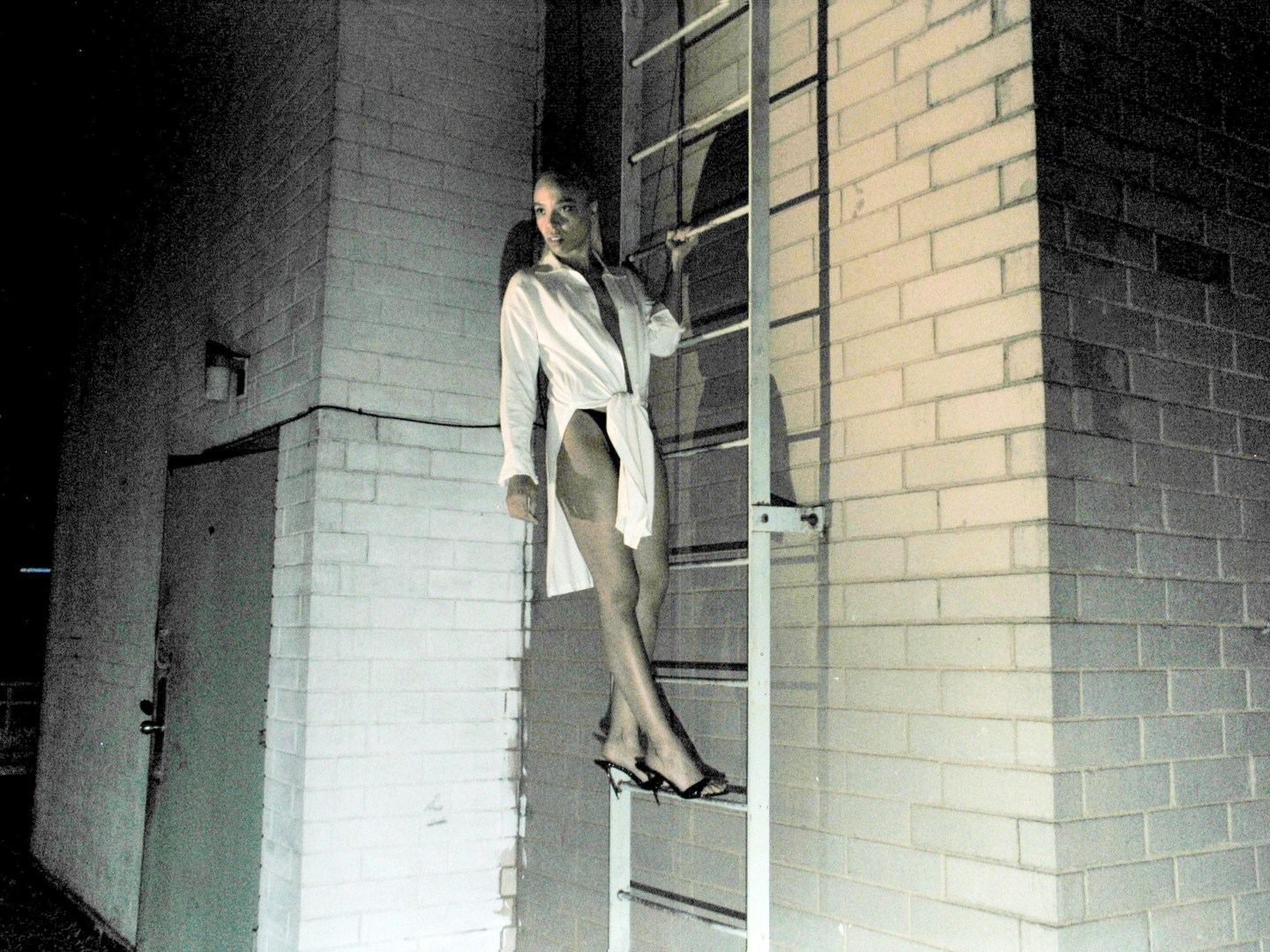

Coming into my voice has been a long process. The [Ache of Victory] EP was an important step in that. On [Big For You], I got to explore and experiment more. When I finally really shed that fear, I found a real confidence. And then with [Big For You], I challenged that confidence to see how much more I could do.

Have you always thought of your melodies before coming up with lyrics?

I’m lyrics-melody first. Talking to some friends who [write melodies first] and then are like, “Okay, now I’ve gotta go write the words,” I’m like, “What?” I wanna try that, actually. But I feel like if I left [the words] to the end, I’d get stuck. Words dictate melody for me.

So do you generally write down ideas you have and then come back to them when you’re writing melody, or does it all happen at once?

It changes all the time. Recently, as an exercise, when I’m working with other people and we’re in the moment, I’ve been trying to just word vomit and see what comes out. I love editing, so I’m then going back in, like, “There’s a good piece in this stack of jumble.”

You’ve said trying not to be as precious about your work was a big part of making this album. Was it hard for you to cut stuff that you initially thought was great?

I tried to practice that throughout. Nothing ever felt fully stuck. If it didn’t feel right, we’d break it down and rebuild. We have so many versions of these songs. If it was getting too crazy or going in a direction where we felt a little lost, we’d bring it back to the heart, like, “Okay, let’s go back to the piano, just voice and instrument, and then build it again.”

I read this quote recently: “Listening is to leaning in with a willingness to be changed by what you hear.” I think that’s what breaks down the preciousness; you have to be willing to be changed. I’m not saying I was perfect at it, but I was actively trying to stay nimble in the process, and to listen to myself and others.

“It was a time of such heaviness, and I had such a strong desire for levity. Trying to keep that up is not always fun.”

Tell me more about working with Daniel Aged. Did you immediately click with him in your first session, or did it take a while?

I couldn’t tell what our vibe was. You’re not gonna read him at first. I was like, “Does this guy hate me? Are we having fun?” He was just making stuff [on his own], and I was really shy — I know him so well now, he’s like my brother — and then he went to the bathroom and I sang all my stuff, and he was like, “We have a song.” I still didn’t know if it was going well; I was nervous. Then, at the end of it, he was like, “Wanna do this again tomorrow?” And we just kept going. He was in L.A., so I did most of my recording there, even when I was still living in New York.

Does it feel easier to work at your own pace in L.A. than it did when you lived in New York?

Yeah, it feels very conducive to being a hermit and working that way. In New York, I only know how to be an extrovert, but I’m also a very introverted person, and [L.A.] allows me to be that. I don’t know. I was so young living in New York that I don’t know what it would feel like now.

Being here now, I keep thinking of being in transit. “Lily of the Nile” feels like a train. “Fire Escape” feels like flying or falling. It’s an elemental theme in the album: There’s this tension and release, motion and stopping, pause and play. It’s a cliché, but I think the moments of stillness inside the chaos are where I thrive.

You address that visually in the video for your first single, “Noise,” which shows you walking very slowly toward the camera in the middle of Times Square, during what looks like rush hour. You lived near there for a while, right?

Yeah. It’s so crazy, but I love it. I feel like I can really get in my zone there. My songs are all such imprints in time of who I was when I wrote them. I was living in Times Square when I wrote “Noise,” and the EP.

For the album, I wanted to come in a bit fresher and not draw so directly from [my personal life]. It goes back to the active listening thing; I wanted to be really present with what I was feeling and wanting to hear in the moment. It was a time of such heaviness, and I had such a strong desire for levity. Trying to keep that up is not always fun. But finding levity in the writing, in the making, was a challenge I really cared about for this album. [It was partly] to feed my soul, but I also want you to hear it.

Hopefully you do, but hopefully you also feel the tension of trying to keep that levity, because it’s human to not be able to keep it up all the time.

It sounds like — in your writing, at least — you’re always working against your current situation, looking for moments of stillness amid chaos and levity in heavy times.

It’s funny because the moment I stepped away from being so wrapped up in the process, so excited by the sonic worlds I’d tapped into, or the new things I was trying with my voice — blah, blah, blah, blah, blah — I’d be like, “Oh, this is heartbreak.”

Photo by Rob Kulisek.

“Fire Escape” is the first song on the album that deals explicitly with matters of the heart. Those huge chords that come in after you sing about falling in love really drive the point home.

The “down”s?

The “down”s. Did you write the lyrics with those moments of catharsis in mind?

It was pretty immediate, wanting to have that hit hard there. It was cool writing that song because that lyric was sounding really morbid — “Day breaks on the fire escape and I’m falling down” — and then I tweaked it just a bit, to “I’m falling in love,” like, “The falling down can relate to love, not just me falling off a fire escape. Even that little choice there was like, “Right, there’s another door that’s lighter over here,” but it can still have ambiguity; there can still be room for otherness.

And the “down”s… We were being really playful, and it felt exciting when we stacked all that stuff on [them]. It really cracked open things sonically.

People talk about falling in love all the time, but it’s not too often — for me at least — that we consider what the “falling” part actually means. Do you think of love as an actual falling process?

Yeah. I mean, it’s like that trust fall vibe. There’s a falling element, but there can also be a “down” element. I don’t know how to sum it up.

You said earlier that the song was about both falling and flying.

Well, no. I just feel like… When I think of the energy, I see that. Yeah.

What are some of your first memories of fire escapes?

Probably in one of my earlier apartments. Me and my mom lived on Clinton Street on the Lower East Side.

Did you spend a lot of time out there?

I mean, being a young person in New York City, you’re on that fire escape into the wee hours. It’s such a vibe, you know? You can just go out there and think about things.

Other than “Fire Escape,” I think “Moth Dance” is my favorite song on the album. Tell me about your guitar solo.

My teeth solo? I’m really glad you asked. It just happened, you know? Sometimes, you have to pick up a guitar and play it with your teeth. I’ve always thought of that song as the home of the project. It was one of the earliest ones, and it feels connected to the EP, but moving forward tonally and breaking away from that place. The other songs have kind of been the splinters off of that.

[“Moth Dance”] also holds a lot of the tension release stuff that influenced the rest of the album, the pauses and the breath. I say the home, but also maybe the heart, because there’s that heartbeat rhythm through it.

“When I say ‘big for you,’ it always translates in my head to ‘I love you.’”

Talk to me about your relationship with rhythm. Ache of Victory was almost uniformly slow, but Big For You changes pace constantly. There’s also the AOV remix EP, where you let other artists people totally re-imagine the rhythms of your early songs.

That’s what was fun about not being so precious, and thinking about these songs like different worlds. We played a lot with making things faster, pushing each thing as fast as it could go, and if it was too much, we’d be like, “Okay, this doesn’t feel right.” I’ve learned that I love reimagining things. I love doing covers live.

What do you like to cover live most?

It’s a mood thing. It’s very context-based. Recently, I’ve been covering Joni [Mitchell]. I love to cover [Carole King’s] “You’ve Got A Friend.” I’ve done a lot of shows in non-venue venues, and I like catering to the space and the crowd when I’m thinking about a cover.

It’s interesting to think about covers in the context of your vocal style — that really striking, sonorous low range you can hit. Were there any other contralto singers you looked up to when you were still finding your voice?

I listened to so much different shit. I was obsessed with Ween and Prince and… I don’t know. My parents are such music lovers, and they had, in hindsight, really good taste. I feel like I’m still rediscovering [artists] I grew up with, like, “Let me really tap into what’s going on here because this is really good. I didn’t know.

Please tell me more about the Ween obsession.

I mean, my dad [(Marc Anthony Thompson aka Chocolate Genius)] was obsessed with them. It was kind of our thing. We went to a concert not that long ago. He has a Ween belt.

I love an artist where everything is like, “What was this chapter?” Each song is a different vibe. With the new album, I was definitely trying to [combine] different worlds and see how they could exist in one home.

You’re quoted in Big For You’s bio as saying its title “touches on the causal versus the intentional dance we play between being full of you and full for you. Can you expand on that a bit?

It’s about the complexity of the magnitude of space we take and the space we fill up in love, being big for you or big because of you. When I say “big for you,” it always translates in my head to “I love you.” It can be really simple and it can be really complicated.

I love duality. I love not fully defining something. This album isn’t mine anymore; it’s yours. And however you define it, I leave that to you. But the “you,” for me, is not fixed. It could be you, or it could be me.