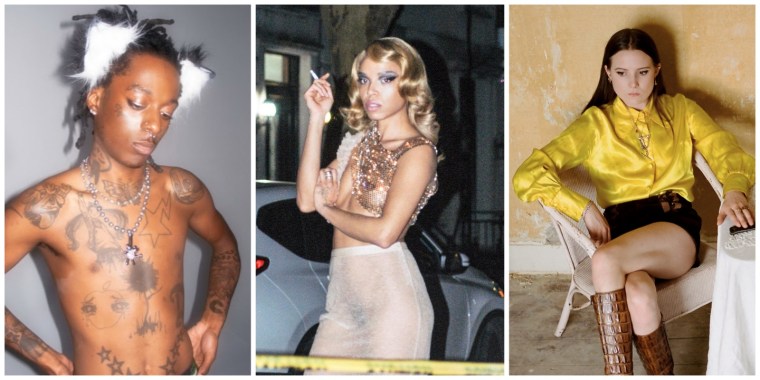

Yasmin Williams

Ebru Yildiz

Around a minute into “Dawning,” at the end of a solo acoustic guitar introduction that rises and rests at its own calm pace, Yasmin Williams pauses to let a harmonic chord ring for a full eight seconds. It has the feeling of a deep breath before the start of a walk into the sunrise. When Williams returns, she’s joined by Aoife O’Donovan, who sings a melody without lyrics — vocals of any kind are a first in Williams’s music — and bare-bones percussion. Across the song’s six minutes, Williams and O’Donovan pause repeatedly, at the end of a movement or a run, and pick back up when it feels as though the song is ready. There is a new pace and a new dynamic each time, new phrases and melodies.

This is a new approach for Williams. Her first two albums, 2018’s Unwind and 2021’s breakthrough Urban Driftwood, showcased her as a singular presence on the guitar. She seemed to borrow equally from Midwest emo and American primitive guitar, a rapid tapping style inspired in part by playing Guitar Hero as a kid and honed further by playing with the guitar face-up on her lap. But while her style was unique, her structures were, she says now, more conventional. She often shied away from silence, and though her pieces were entirely instrumental, they still tended to conform to recognizable verse-chorus-verse patterns.

What changed? “Maturity,” she says now on a call from her studio in Alexandria, Virginia. “Just living life and not being the angsty teen I was when I first started playing. Silence now is something that I don’t get as much, so when I can create it, it means more to me than it did in the past. I’m more comfortable with silence now than I was earlier in my playing days. I’m not afraid to meander and let a song go to different places. It doesn’t have to be as regimented and rigid in structure.”

Her third album, Acadia, out now via Nonesuch Records, is expansive both structurally and sonically. Collaborators weave in and out — O’Donovan, saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins, neo-traditional bones player Dom Flemons, and guitarist William Tyler, another guitarist stretching the limits of the American folk tradition — and the sound shifts with them. The bluegrass of “Hummingbird,” a collaboration with Allison de Groot and Tatiana Hargreaves, exists on a different plane to the electric “Dream Lake,” which features jazz-rock drummer Malick Koly. Williams has always been in conversation with folk conventions, but Acadia runs completely counter to tradition. Written in three parts, it is constantly in flux. There is sax and harp and electric guitar, songs written on the banjo and turned into jazz-rock tracks. There’s a key change at the end of “Malamu,” the closer, that seems like a final flourish, a statement against categorizing Williams as anything other than an artist interpreting her instrument and her craft in her own unique way.

What were you looking for in a collaborator on this record?

I was looking for someone who seemed super comfortable and confident in their playing style, someone who is as close to masterful as you can get on an instrument, and someone who was just nice to work with. There are 19 folks on this record, and I picked all of them. They all serve the function of masterful playing and fitting into the worlds I created in the tunes, which are complex and difficult. There’s a lot of tempo changes, key changes, technical things that are difficult about the songs. For them to pick that up quickly and insert themselves in a seemingly personal way was super special for me to witness and hear. I just wanted people who were comfortable doing that, not afraid to improvise, not afraid to take a leap of faith.

You mentioned the worlds that you’ve built around these songs. Do you feel that they each have their distinctive worlds?

I think each song has its own narrative and journey. I ordered them in this particular way because they come together in groups of three. The first three songs live in an acoustic world; they’re very organic. The next three are almost like suites, bringing in more instrumentation, experimenting more, and including vocals — a different thing I decided to do on this record. They’re ethereal-minded. The last three tracks are electric, with electric guitar prominent and a different vibe altogether, but they still bridge the gap between the first two sections. They’re organic in a different way and also ethereal in a different way, but they bring even more instrumentation. I think of the album as three sets of trios, like suites. Each song has its own world, and I was in various moods when writing these songs. Pretty much every song is super personal to me and represents something I was going through at the time of writing it.

Ebru Yildiz

What’s it like communicating the personality and personal nature of a song when most of the time you’re not using lyrics? Is it something that you’re often relying on your audience to pick up on, or is it more for you?

For me, it’s really freeing not to rely on lyrics. It’s freeing not to tell the audience what to think. They can interpret the songs how they want to. If they happen to get a record and look at what the song’s about, cool, but I’m not banking on that. I like to put music out into the universe and let it take people where it takes them. People are going through whatever they’re going through, so a song will hit someone differently than it hits someone else. For me, the songs are definitely about various things like relationships and the difficulties of being a musician and traveling so much. I listen to tons of instrumental music, so I prefer not to have to worry about being told what’s going on. I can just let the music wash over me and figure things out for myself.

You’ve talked in the past about “ruminating” on a particular note when you write. What does that process entail? What does it mean for you?

I think it’s kind of how I’ve always been. I’ll just play a phrase over and over again, and if it sits right with me, then it’ll stay; if not, it’ll disappear. That’s how I process music and use it to process the world around me. Music gives me space to think and let my emotions out in a constructive way. It’s not a conscious thing. I’ll remember it, write it down, or record it. If months go by and nothing becomes of it, cool. If years go by and I remember the phrase again and want to use it, cool. It’s a vital process. I need to give myself time to play phrases over and over and see how they intertwine, see how they play with each other. It’s a very necessary part of the process.

It seems like you get into a different mental state when you’re repeating these things. It sounds almost meditative.

It is. A lot of the time, I’m sometimes not aware that it’s even happening. Like, I’ll start practice at 6, and it’s 10—what happened? It’s definitely meditative in a way. It’s probably the closest I’ll ever get to meditation because when I’m not doing that, my brain’s on like 100 all the time. If I don’t have space to do that, it would be very difficult for me to write anything.

This goes as granular as single notes, not just phrases—the sustain of a particular note.

Absolutely. For me, it’s imperative to let notes ring. I don’t know why; that’s just how I’ve always been since I started playing guitar. I love when notes ring and have time to develop, even if I’m playing something that’s technically fast. Letting the notes ring and develop is necessary to me, especially on acoustic guitar, because that’s where it shines brightest — how the notes change over time.

Ebru Yildiz

Where do you think your relationship with folk music is right now?

I appreciate it for what it is. I love listening to old-time music. I honestly love how a lot of it sounds the same. Even people who are steeped in the tradition aren’t sure if it’s this song or that song because they sound exactly the same. I think that’s really cool that they have such a cemented style. For me personally, it’s not flexible enough sometimes. I feel like the aesthetic of folk music is not in line with what I’m trying to do sometimes.

Your use of the banjo and the increasing use of it—you’ve always used the guitar as your primary songwriting instrument. Have you been using the banjo as a primary songwriting tool, or has it been mostly for punctuation?

I’m learning more repertoire on the banjo to get more comfortable playing it. Using it in my music was not the plan at all, really. But I’m starting to write songs now with banjo as the leading instrument or the only instrument, and it’s a lot of fun. It’s not something I would have been comfortable doing years ago. I think I originally got my first banjo five years ago and sold it because I was like, ‘This sucks. I’m not learning as quickly as I wanted to.’ Maturity again. Then I got my most recent banjos and was like, ‘You know, banjo is actually really fun to play.’ It’s really nice to be a beginner at something now and give myself a new perspective. I appreciate that more. So yeah, it’s definitely becoming a songwriting tool for me. I’ve written songs with it, and it’s included in some of the songs on Acadia. It’s just really fun to play.

But very different sustain. Does that push you even further out of your comfort zone, knowing that you’re not going to get that same sort of resonance?

Yeah, that’s really interesting you bring that up because I find myself gravitating toward melodic style, which gives you that sustain in different ways. Instead of playing a scale on a single string, you play a major scale going up the fretboard and let the open strings ring out. There is that ringing aspect in melodic style that I appreciate. That’s why I gravitate toward that style in particular. It’s tricky to get notes to ring out on the banjo; your finger placement has to be exact. But once it works, it sounds great.