Getty

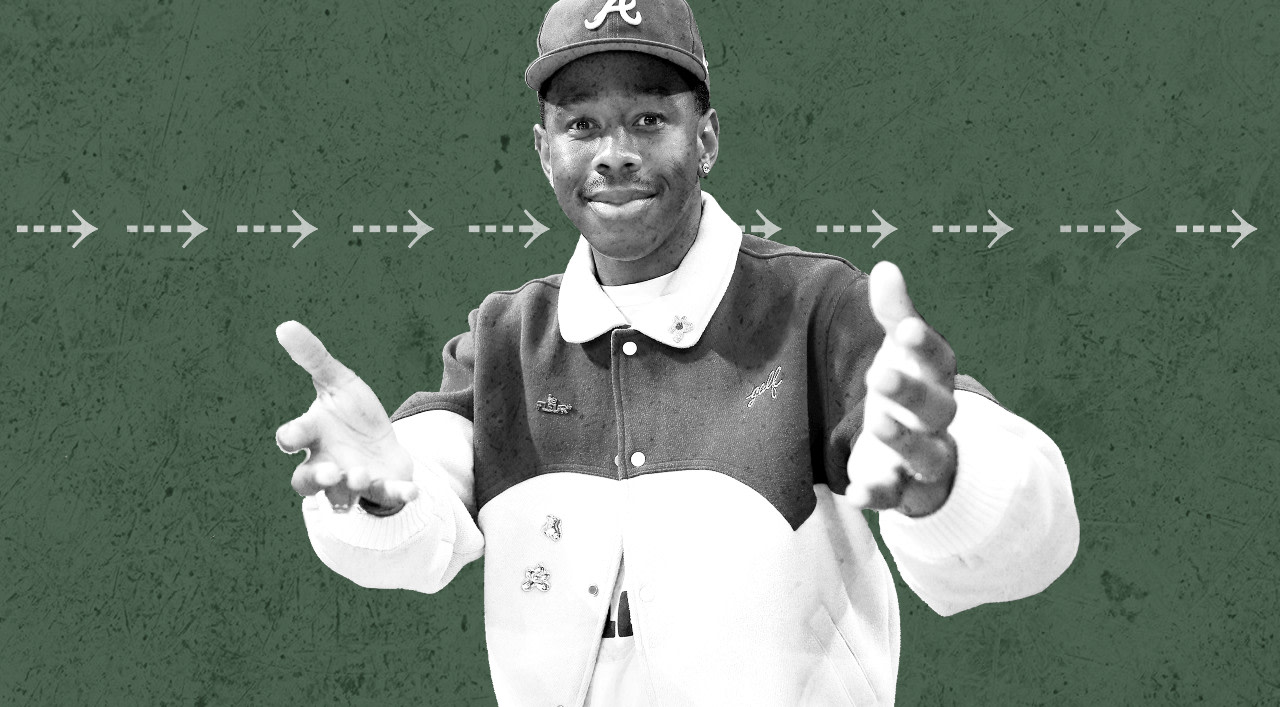

Since he first emerged as the de facto leader of Odd Future, Tyler, the Creator has established himself as a charismatic firebrand, the kind of artist whose outspoken ways position him as a radical while his music has mutated over time, from button-pushing horrorcore rap to lush and melodic pop fantasias inspired by his idols, Stevie Wonder and Pharrell. As he releases his seventh studio album, CHROMAKOPIA, Tyler remains a generational idol whose fans have grown with him, from adolescence to maturity.

Ahead, find The FADER’s definitive guide to the rapper that acts as a roadmap through the past 15 years of Tyler’s career, as well as serve up a few funny, weird, and interesting pieces of ephemera along the way.

Tyler breaks out: the Bastard/Goblin era

When Tyler, the Creator’s debut album, Bastard, landed on Tumblr on Christmas Day 2009, it was a significant but not defining piece in the Odd Future jigsaw puzzle. Populated with guest spots from that crew (Earl Sweatshirt, Domo Genesis and Hodgy Beats all appear), Bastard has the distinct air of something created by then-17-year-old Tyler to amuse friends first and explore musical ideas second. Lyrically, parts of the album haven’t aged well, with the sick humor feeling less edgy following a decade-plus of comedians crossing the line and yelling “triggered” in response. Look past the rape jokes and homophobic slurs (and you’re forgiven if you can’t) and Bastard establishes some of the topics that Tyler would go on to finesse on future releases: namely, issues with his absent father and an isolationist streak that immediately separated him from every other rapper that wasn’t already in his tight-knit circle.

“Fuck a deal, I just want my father’s email / So I can tell him how much I fuckin’ hate him in detail,” he says on the album intro in his trademark deep gurgle of a voice. Provocative yet wounded, insensitive and owning his own vulnerability, it was immediately apparent that this jumble of contradictions made for a magnetic combination.

Goblin, released in 2011, took the Bastard template and super-charged it. “Yonkers” announced Tyler to the world, an authoritative and spiky dissection of his persona delivered over a minimal and grinding self-produced beat. “Yonkers,” like much of Goblin, is Tyler sanding down the edges while retaining enough pointy-elbowed jostling to maintain his image at the time as a Supreme-clad provocateur. It’s a herculean task and one that Tyler reckons with on the album, which opens with him discussing fame in a therapist’s office. Goblin may have been eyed as a crossover album by the team around Tyler but it’s not an album that has widespread acceptance on its mind. “Nightmare” and “Golden” make up a tranche of songs where Tyler’s tendency towards nihilism and bleak horizons are on full display. The “kill people, burn shit, fuck school” refrain of “Radicals,” meanwhile, is pure adolescent rage, the kind that feels world-defining in the moment and mortifying in retrospect.

At the time it was understood that Tyler was a child of the internet with a twisted sense of humor; making him an artist who could upset the status quo in an industry still coming to terms with changes to technology, as well as an Obama-era society built on a wooly sense of hope and positivity. Those traits that once defined him, however, soon fell by the wayside as the rest of the world caught up and, in some cases, surpassed his energy. The longer lasting hallmark of the Bastard/Goblin era is one of Tyler’s ability to create and define his own autonomous world; one filled with rage, humor, absurdity, transgression, punk aesthetics, and little to no space for outsiders.

Goblin, released in 2011, took the Bastard template and super-charged it. “Yonkers” announced Tyler to the world, an authoritative and spiky dissection of his persona delivered over a minimal and grinding self-produced beat. “Yonkers,” like much of Goblin, is Tyler sanding down the edges while retaining enough pointy-elbowed jostling to maintain his image at the time as a Supreme-clad provocateur. It’s a herculean task and one that Tyler reckons with on the album, which opens with him discussing fame in a therapist’s office.

Goblin may have been eyed as a crossover album by the team around Tyler, but it’s not an album that has widespread acceptance on its mind. “Nightmare” and “Golden” make up a tranche of songs where Tyler’s tendency towards nihilism and bleak horizons are on full display. The “kill people, burn shit, fuck school” refrain of “Radicals,” meanwhile, is pure adolescent rage, the kind that feels world-defining in the moment and mortifying in retrospect.

At the time, it was understood that Tyler was a child of the internet with a twisted sense of humor; he was an artist who could upset the status quo in an industry still coming to terms with changes to technology and an Obama-era society built on a wooly sense of hope and positivity. Those traits that once defined him, however, soon fell by the wayside as the rest of the world caught up and, in some cases, surpassed his energy.

The longer lasting hallmark of the Bastard/Goblin era is one of Tyler’s ability to create and define his own autonomous world; one filled with rage, humor, absurdity, transgression, punk aesthetics, and little to no space for outsiders.

Tyler opens up: the Wolf/Cherry Bomb/Flower Boy years

Wolf, released in 2013, marked Tyler’s first attempt at taking that grayscale universe and injecting it with a little color. Released via the Odd Future label (part of a lucrative deal signed with major Sony), it is an album on which Tyler established his desire to grow as a producer while learning to exist in a world that has taken his villain persona at face value (Tyler was banned from entering the U.K. in 2015 with then-Prime Minister Theresa May citing his lyrics as a cause of concern). It also marks the first time Tyler would welcome outsiders to the party. He chose wisely, with Erykah Badu featuring on “Treehome95” and Pharrell singing about feeling jealous and insecure on “IFHY.” Tyler has never shied away from his hero worship of Pharrell, and Wolf is the album where he first began to make his love for the Neptunes artist apparent in the music. “Domo23” has an intergalactic swing, with horns and synths firing shots across the bow in a sci-fi showdown. “Lone,” meanwhile, is a lush admission that underneath the fame, money, and success lies someone feeling isolated. Both songs have the trademark Neptunes jazzy chords and future-funk, as does the Frank Ocean-featuring “Slater.”

In addition to Pharrell, Tyler’s music has always had a punk rock energy to it. This came to the fore on 2015 album Cherry Bomb which often feels like he started a band in his garage just to feel the amp vibrate through his spine. Alongside the title track, songs such as “Pilo” and “Deathcamp” have a loose and scuzzy feel that feels like a comfortable mid-point between the gnarled horrorcore of his early albums and the blockbuster fantasias to come. Cherry Bomb is perhaps the least well-regarded of Tyler’s albums, both by fans and Tyler himself, who neglected to perform anything from it during his 2024 Coachella headline set. However, a playful experiment, it maintains a certain charm.

Perhaps it is what followed that has pushed Cherry Bomb out of mind for many Tyler fans. 2017’s Flower Boy marked a newly heartfelt and lush tone to Tyler’s music. Where once he pretended to eat roaches to get a reaction in his music videos, Flower Boy’s self-directed visuals were filled with Wes Anderson-style whimsy and color. Songs like “Mr. Lonely” and “See You Again” arrive in similar pastel shades. “Tell these black kids they can be who they are,” he raps on “Where This Flower Blooms,” as he repositions his career not as the tyre-tracks of a distant divider but a blueprint to other self-defining outcasts. Notably, Flower Boy also marked Tyler’s public coming out moment. Though he had long hinted at romantic feelings for other men, the ironic stance used as a defense for his most dark-hearted jokes meant anything approaching sincerity came with a similar get out clause. That pretense is dropped on songs like the luxuriant “I Ain’t Got Time” or “Garden Shed,” on which he raps sensitively about being closeted.

Tyler grows up: Igor and Call Me If You Get Lost

If Flower Boy represented Tyler’s coming out moment it also raised questions about what he would do without the alter-ego to lean on. If his early work was defined by antagonism and Flower Boy by revelation, Igor was Tyler reckoning with contentment and allowing his musicality to take flight. The 2019 album features some of his most interesting experiments, including the rib-rattling “New Magic Wand” and “Earfquake,” a slick R&B song cut through with a baby-voiced Playboi Carti. Unpicking a knotty relationship with a man who leaves to return to a female ex, Igor also marks a newfound lyrical maturity in Tyler’s work. “I hope you know she can’t compete with me,” he sings defiantly on “Gone, Gone / Thank You,” before switching to something less performative: “Thank you for the love/Thank you for the joy.” There is growth in such a sentiment, an acknowledgement of what the relationship meant where once there would have likely been insults and dismissal.

While the Igor-era allowed Tyler to dress up as an artful and androgynous figure complete with a blonde bob wig, Call Me If You Get Lost allowed him to cosplay as something many have demanded from him all along: a serious rapper. Styled like a Gangsta Grillz mixtape, down to DJ Drama’s hyped up yelps, 2021’s Call Me If You Get Lost allowed Tyler to be playful and nostalgic, two traits he has always excelled at. It also created space for him to really rap. “Lumberjack” is up there with “Who Dat Boy” and “AssMilk” in the canon of songs where Tyler shows the world that he has bars when he wants to. Elsewhere on the album he picks apart another romantic entanglement (this time involving the partner of a mutual friend) as well as straying into more thought-provoking territory, including his thoughts on the whiteness of his audience (“Manifesto”). Like Igor, Call Me If You Get Lost is representative of a period in Tyler’s career where, having established himself artistically and freed himself emotionally, he was open to wherever his inspiration took him.

Perhaps it is what followed that has pushed Cherry Bomb out of mind for many Tyler fans. 2017’s Flower Boy marked a newly heartfelt and lush tone to Tyler’s music. Where once he pretended to eat roaches to get a reaction in his music videos, Flower Boy’s self-directed visuals were filled with Wes Anderson-style whimsy and color. Songs like “Mr. Lonely” and “See You Again” arrive in similar pastel shades. “Tell these black kids they can be who they are,” he raps on “Where This Flower Blooms,” as he repositions his career not as the tyre-tracks of a distant divider but a blueprint to other self-defining outcasts.

Notably, Flower Boy also marked Tyler’s public coming out moment. Though he had long hinted at romantic feelings for other men, the ironic stance used as a defense for his most dark-hearted jokes meant anything approaching sincerity came with a similar get out clause. That pretense is dropped on songs like the luxuriant “I Ain’t Got Time” or “Garden Shed,” on which he raps sensitively about being closeted.

CHROMAKOPIA

On his latest album, released in October, Tyler goes deeper into his family history and thoughts on his own fatherhood than ever before. Set to a thrilling combination of triumphant party raps and heavier, guitar-led tracks, Chromakopia is a compendium of Tyler’s most immediately pleasing modes.

“Noid,” the album’s Zamrocking lead single, marks a return to the therapist’s chair, with Tyler sharing feelings of being trapped by fame and seeking to distance himself from ever having to pose for a selfie again. Panic is also felt on the pregnancy scare narrative of “Hey Jane.” Seeking help, Tyler turns to his mother who appears in voice note form between songs. She is also heard on “Like Him,” on which Tyler worries that he will repeat his father’s failings should he start a family. It feels like a full circle realization on a career which began with white-knuckled rage and slowly graduated to a blissed-out acceptance.

Seven albums deep is often a time when artists allow complacency to take hold. The fact that Tyler is still learning new things about himself ensures the ongoing examination of his psyche remains as fascinating as ever.

An ode to Tyler’s wonderful hair (and wigs)

Like a pop star, Tyler, the Creator often announces when he’s entering a new era by changing his hair. It’s really been a more recent phenomenon, starting with Igor, as his albums have grown to become more complex and character-driven. Then, it was a blonde flat top molded from his real locks for the album cover and the iconic, bleached-blonde, fuck-ass-bob bob that dominated the majority of the album’s release and ensuing promo. For Call Me If You Get Lost, he didn’t go as dramatic, but paps did often snap him stepping out with funky stenciled designs in his buzz cuts; fittingly, this was when the rapper was also putting renewed energy into his fashion brand, Golf Wang, as he strove to carve a clearer line between his clearly adventurous artistic eye and a real style pursuit.

He decided to go all out again for Chromakopia, pairing a Jason-esque mask with another highly structural style that resembles the staggered edge of a castle turret. Interestingly enough, the look has been received as a mere footnote, leaving fans to wonder on TikTok, “why we never talk about the hair,” only to receive responses like, “because it’s Tyler.” At this point, wild costumes and wild hair have become synonymous with the continued evolution of the Tyler, the Creator project. My only question now? Who’s making his wigs? —Steffanee Wang