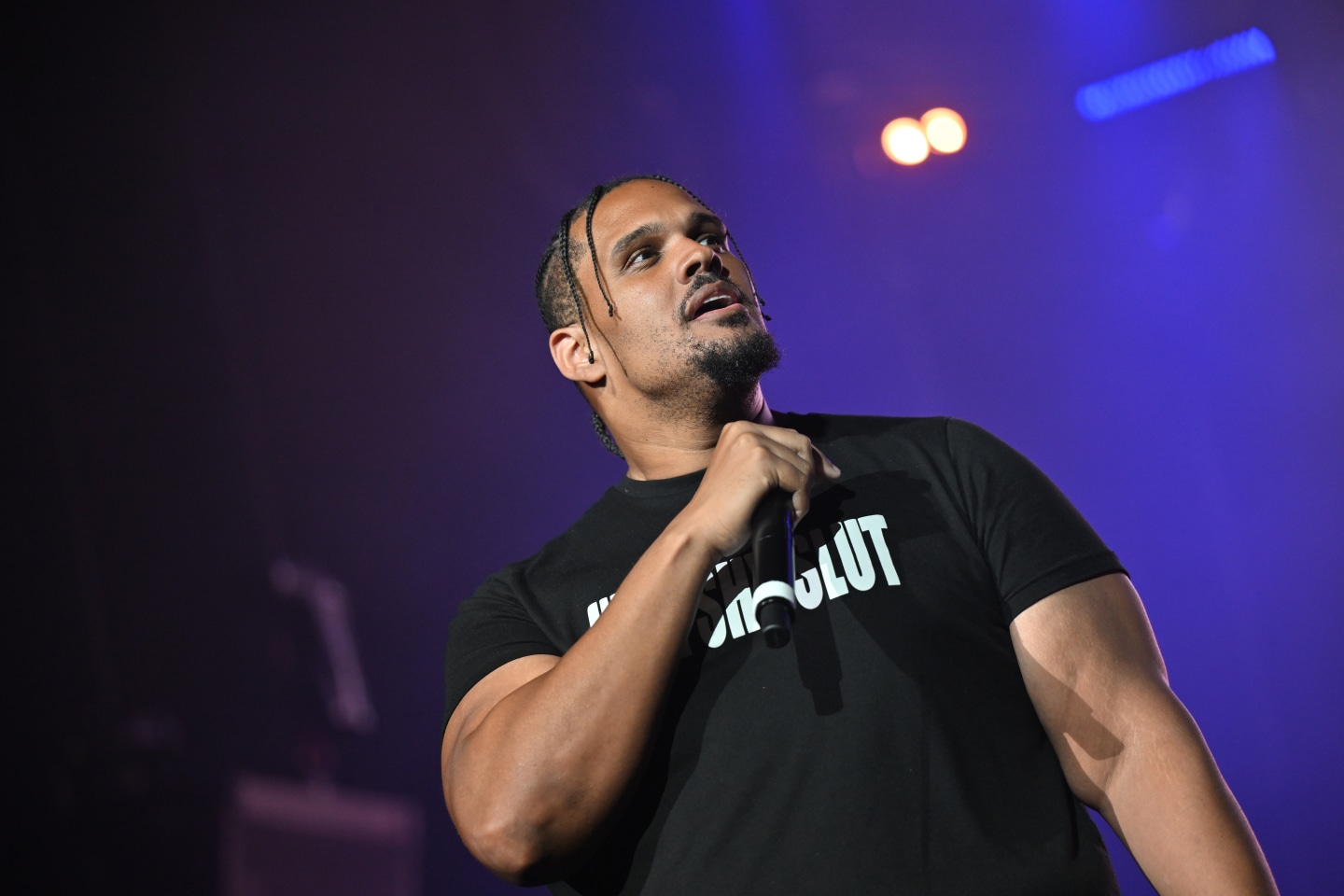

Beatking. Photo by Paras Griffin/Getty Images

Before I ever heard a song by Beatking, his shirts announced the vibe, bearing 150-point Impact font slogans like “GUM IS NOT TOOTHPASTE,” “Squirting is cool but it stank,” and “STOP MOVING TO HOUSTON.” The tees were a product of necessity — the cheapest way for Beatking to show up at the club with a fresh fit every weekend — and, like the Houston rapper and DJ’s music, laser-focused on pinging the most carefree part of our brains. “I can rap my ass off, but I realize that bitches don’t want to learn trigonometry in the club,” he said back in 2014. Beatking, who passed away on August 15 of a pulmonary embolism at just 39, elevated carefree club dispatches into self-fulfilling pick-me-ups; his songs seem to manifest joy in real-time.

His passing marks the loss of a major and singular cultural institution. Although Houston has produced a number of nationally renowned household names, Beatking is more of a local legend, whose music might have soundtracked a wild night with college friends or a life-changing twerk at V Live. For other artists, this sort of regional devotion might indicate an ostensible ceiling to their popularity, the outer limits of how far a relatively territorial sound can travel. By comparison, the army of hometown acolytes Beatking amassed seems to reflect the depth of fans’ admiration rather than the breadth of his appeal. Even music as “low-brow” as this can leave an indelible mark on the soul.

Beatking first rose to prominence in the 2010s after pivoting towards a club-ready sound equally influenced by Three Six Mafia and dance rap tracks like “Stanky Legg” and “Teach Me How to Dougie.” The Memphis lineage of Beatking’s music helps to differentiate his sound from the codeine-nostalgia non-Texans and major label rappers tend to invoke when they think of Houston — you could easily slide one of his tracks in between fresh releases by Duke Deuce or Tay Keith without raising any eyebrows. And it isn’t too hard to see how Beatking’s sound has trickled down to the city’s newer generations (TisaKorean used to play Beatking when he DJed in high school), whether they explicitly cite his influence or not. “The stuff I was doing 10 years ago, you can see it in somebody like [Megan Thee Stallion] today,” Beatking said in a 2020 interview. “She’s 25, so that means she was listening to me when she was 15… I’ve been on.”

First-time listeners might label Beatking raunchy, ridiculous, or even flat-out rude, with chants like, “Biiitch you done got thick since you had that baby,” on 2018’s “Molly Monster,” and “she be fuckin on these rappers I don’t care (none of my business)” on last year’s nearly-earnest paean “Bottle Girl.” These impressions are not unwarranted, but they elide the nuances of the Houstonian’s signature sound and the occasional emotional depth his music can evoke — Beatking only peers in the rearview occasionally, but his desire to contextualize popped champagne as not only cathartic but earned recurs time and again (see 2010’s “Big Moe” and 2015’s sprawling stream of consciousness “It Doesn’t Matter“).

Even his lesser songs come equipped with oodles of laugh-out-loud charisma and 808s so visceral they seem to communicate directly with your limbs; more than 15 years into the game, the self-proclaimed “Club Godzilla” could probably craft a trunk-rattler or strip club thumper in his sleep. At his best, Beatking is endearingly human, toggling between grindset and hornball activities without skipping a beat.

Though he may not have achieved the same notoriety as some of his peers, Beatking earned plaudits from Texas legends including Bun B, Slim Thug, and Paul Wall, as well as out-of-state nods from industry heavyweights like Drake and Nicki Minaj. His coterie of collaborators highlighted his eclectic taste and impact, spanning features with Armani Caesar, Danny Brown, and 2 Chainz, to name just a few. As validating as these cosigns may have been, they must have paled in comparison to working with Three Six Mafia, an opportunity to contribute to the musical legacy of the group that inspired Beatking the most. Project Pat spit a verse on “He’ll Shoot” from 2019’s Club God 6; Beatking’s favorite rapper Juicy J tapped Club Godzilla for a feature on his 2022 mixtape Crypto Business with Lex Luger, then returned the favor with a menacingly sleazy verse on 2023’s “Back Back.”

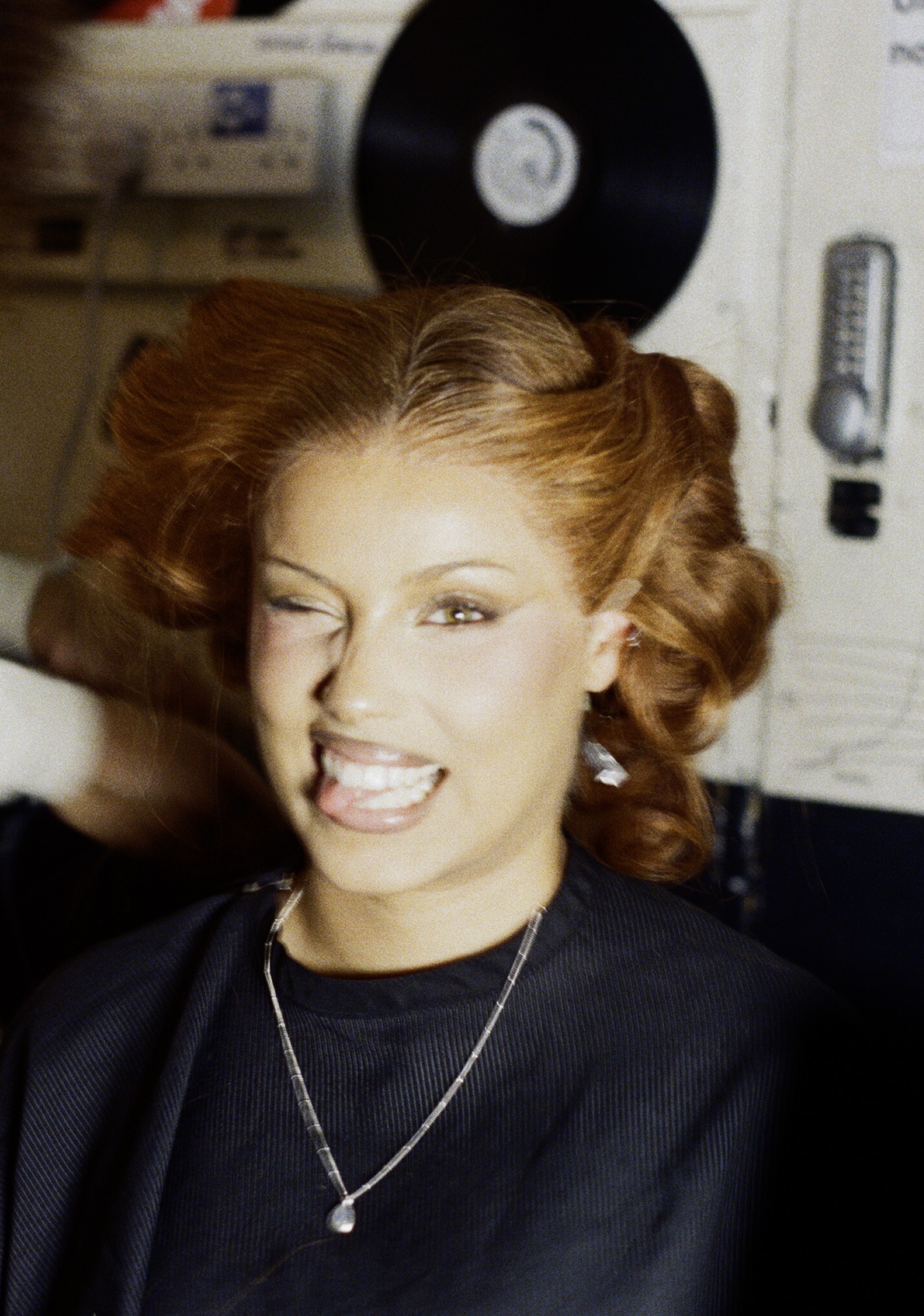

Of particular note are 2014’s Underground Cassette Tape Music and its 2018 sequel Vol. 2, collaborative tapes with Gangsta Boo that helped to elevate Beatking’s national profile. The two rappers connected through a mutual friend, DJ Speakerfoxxx. “We just knew it would be dope,” Gangsta Boo said of their collaboration back in 2014. “It’s just the right time that I go ahead and co-sign [an] up-and-coming artist such as Beatking who was heavily influenced by the [Three 6] Mafia sound.” That cosign helped to draw critics and new fans to Beatking’s music: “After the Gangsta Boo mixtape, it kind of made my fanbase shift slightly,” he explained in 2022. “I just had my first show in New York two weeks ago and it was sold out.”

While Beatking’s lyrics can be crass to the point of misogyny (see last year’s “RIP K Samuels”), these patriarchal impulses are moderated if not outweighed by a North Star of inclusive ratchet behavior — his attitude might be “pimps up, hoes down,” but “pimps” can include ladies who keep it playa like Gangsta Boo and LGBT peers such as Saucy Santana. “For me, I’m a LGBT DJ,” DJ Panda told Fox26 this week. “One thing that I really gave him credit for is that he included everybody in his music. And he came and supported us — he showed us respect, we showed him respect.”

Though Gangsta Boo is the biggest female rapper Beatking worked with, one of his closest collaborators was Queendom Come, who first featured on his 2011 mixtape Club God. “He was ahead of his time,” Queendom Come told Forward Times shortly after his passing. “He was just one of those rappers that worked with a lot of female talent but, most importantly, he made sure the women he worked with got their credit.”

The pair found viral success on TikTok in 2020 with “Then Leave,” which prompted Columbia to sign Beatking, though the partnership, like a previous deal with Sony, was short-lived. Beatking discussed the particulars of his departure from Columbia on the outro to last year’s She Won’t Leave Houston, citing the slow-moving bureaucracy and occasional creative meddling of label politics as part of the reason he prefers working independently. Still, he characterized the deal as a positive learning experience, and this is perhaps the heart of what makes Beatking such a resonant artist.

“2009,” the penultimate song on last month’s Never Leave Houston On A Sunday, found Beatking reflecting on 15 years in the rap game. He “dumbed [his] flow down / started making wack ass beats with only four sounds” to gain traction on the dancefloor; when he couldn’t pay the light bill, his sick mother told him to leave her in the dark so he could push his records to DJs in the club. On the album outro, he admits to tearing up thinking of his late mother when he recorded “2009.” Even if Beatking rarely addresses these struggles in his verses, there’s an implicit catharsis in his “dumbed down” bangers, the celebratory thrill of having a good time against the odds.

Every June 27th or Dec. 4th I think about my legacy i’m tryna leave. When I die I just want Beatking sets played in the clubs every weekend!

— CLUBGODZILLA (@BEATKINGKONG) December 4, 2014