brat”>

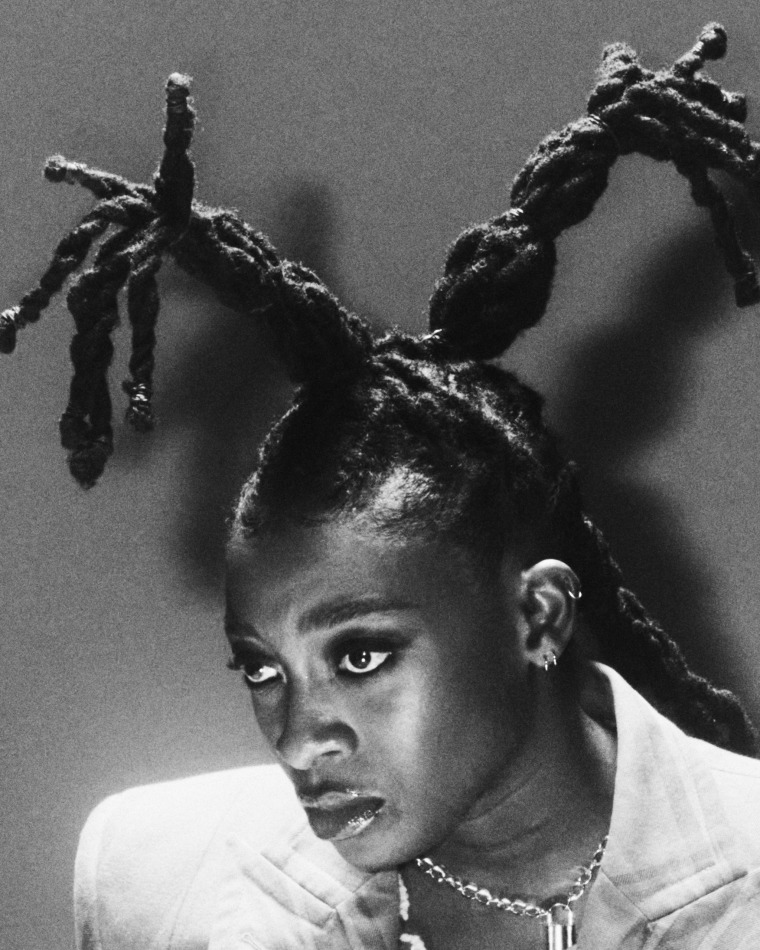

Klaxons

Photo by Annabel Staff/Redferns

If you ever attended Club Cool, a rave held in the heart of Shoreditch around 2007, you might have seen a 14-year-old Charli xcx performing at one of the events. Accompanied by her parents, she would travel from the leafy suburbs of Hertfordshire to share a bill alongside DJs with names like Trash Fashion and Neon Skullz. This was during the peak of new rave, a U.K. scene that ushered in a wave of glow stick-waving riotous dance music buoyed by cheap drugs and the last vestiges of affordable university education.

There was a spiky, DIY quality to the music coming out of the underground that came with a sense of humor to differentiate it from the electroclash sound that preceded it. Klaxons emerged as sci-fi obsessed rave revivalists and beacons of the entire scene after winning the Mercury Prize for their debut Myths of the Near Future and performing with Rihanna at the 2008 Brit Awards (maybe new rave’s “Kamala IS brat” moment). Test Icicles, featuring a young Dev Hynes, reimagined hardcore punk as a dayglo tsunami of drum machines and Playstation references. The proggy Late of the Pier, meanwhile, shone a strobe light on a wizard’s hat with their outlandish and ambitious debut, Fantasy Black Channel. And no new rave night would be complete without the alarm sirens of their “Atlantis To Interzone” or similarly punkish songs by CSS, Digitalism, Shitdisco, Robots in Disguise, Does It Offend You, Yeah? and Crystal Castles.

“Everyone at those shows was out of their mind on ketamine and tossing glitter around,” Charli told Rolling Stone in a 2012 interview, looking back to her formative years playing in grimy disused factories. That whole scene really inspires me. The fashion, the music, etc. Even with its stereotypes and limited scope, it really helped me become who I am as a performer today.”

The influence of new rave was short-lived and largely forgotten by the time the last pair of American Apparel disco pants were ditched from the back of the wardrobe. Charli seemed to move on, too, making her way through a variety of styles from goth-pop to EDM-adjacent bangers, radio-friendly hits, and boundary-pushing dance music with her P.C. Music collaborators. Then, she made a fascinating pivot back to the genre with her new album brat.

brat”>

brat”>

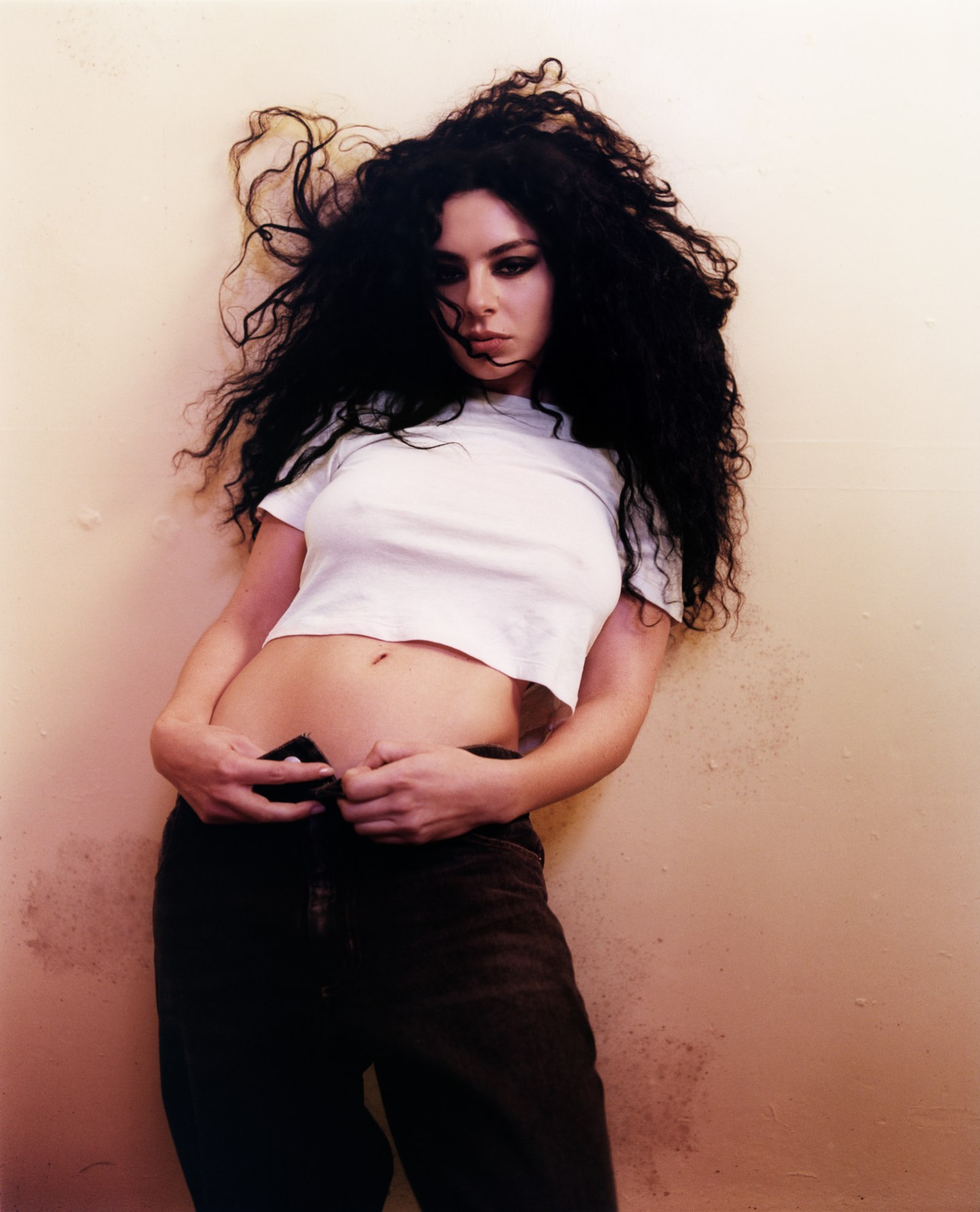

Charli xcx

Harley Weir

Watching as the brat rollout has gone from sublime (“Girl, so Confusing” and the perfectly timed Lorde remix) to surreal (CNN newscasters discovering the brat summer trend amid discussion it may genuinely impact the election) over the past few months. The days of ketamine and glitter have returned, and are invading the mainstream in bizarre and exciting ways.

There is a temptation to see new rave as a time when U.K. indie bands ditched The Libertines as heroes and switched their attention to what was happening in New York with DFA Records and both the Ed Banger and Kitsuné rosters in Paris. There is some truth in that, but it wasn’t as simple as selling guitars to buy synths. DJ sets and club nights took precedence over live performances at the same time as music was discovered online via MySpace. In London that meant clubs like Trash where DJ Erol Alkan would play “We Are Your Friends” by Justice vs Simian and Soulwax remixes of bands like Gossip, MGMT, and Ladytron.

It was a time of unabashed garishness that can be traced through to Charli’s punchy and confrontational “Von Dutch,” named after an aughts-era accessory that predates even new rave. Billie Eilish’s “try it bite it lick it spit it” verse on the “Guess” remix shares its cadence with “Technologic” by Daft Punk, a huge influence on everything new rave. Then there is “365,” the whirring album closer that hits like a pneumatic drill and turns the bouncier “360” into perfect Trash fodder. That song was first played at Charli’s PARTYGIRL shows, including the hugely over-subscribed Boiler Room set in Brooklyn made up almost entirely of remixes of unreleased brat tracks. She has teased the existence of a collection of “feral” edits that will pull the album even closer to its club kid origins.

brat, like new rave, is as much about aesthetic as it is music. Charli is smart enough to avoid a time of lurid looks when glasses were worn without lenses, cassettes were hung as pendants on chains and the “disheveled kids TV presenter” look was available off the rack at Topshop. There is a shared feeling of hedonism and rejection of healthy living in both, however. Charli has likened brat to a “pack of cigs [and] a Bic lighter,” something in keeping with a time when smoking indoors was still legal in the U.K.

It would be easy to credit the freedom and bad taste of the new rave era with a pre-smart phone age but the mid-2000s was not a time that went undocumented. Waking up to discover 40+ pictures from a night out posted on Facebook was standard routine while clubs and shows were captured in full exposure by photographers such as The Cobrasnake. It was no surprise to see his photos from Charli’s birthday earlier this month, starry, candid, sweaty, FOMO-inducing, and oddly vintage.

Suitably for an album rooted in 2000s club nostalgia, brat is an album about being in your 30s. It’s a collection of anxious and contradictory songs written at a crossroads that ask, “should I do a little line or start a family?” No matter what CNN or anyone else who Googled “brat green” this summer will tell you, it’s neither delivered from, or aimed explicitly at, a Gen-Z mind. This millennial crisis of empowerment and disillusion is conveyed in plain-spoken verses about complicated social dynamics, jealousy, and missing friends that are then married to music pulled straight from the times she’d only go to clubs if her mum and dad were free to take her.

In that same Rolling Stone interview she underlined the importance of those times, saying that when she started all she wanted was “to make music that the rave kids could dance to.” More than fifteen years later, brat is the album that has both completed the circle and pushed that wide-eyed teenager into an unexpected new stratosphere.