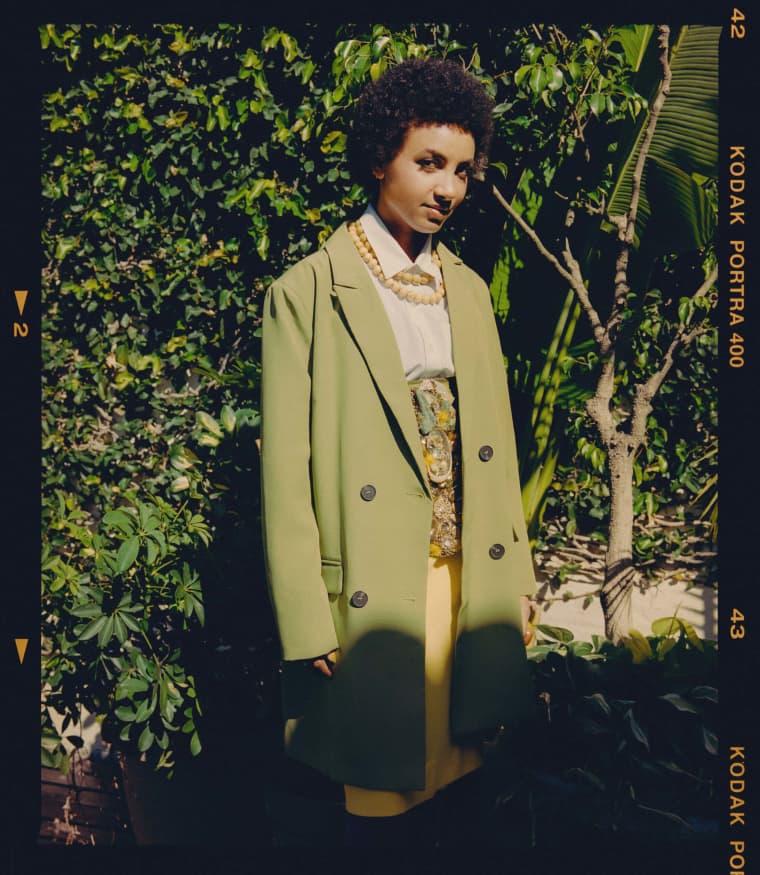

esperanza spalding (left) and Milton Nasciemento. Photo by Lucas Nogueira.

esperanza spalding first heard Milton Nascimento’s music as a grad student at Berklee. “Some Brazilian friends were over for dinner, and they were so scandalized that I didn’t know who he was,” she recalls. “I was supposed to be a jazz musician.”

Nascimento came of age in the ’60s and ’70s in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, helming the Clube da Esquina collective that, alongside the concurrent tropicália movement, formed the foundations of the next 50 years of música pop brasileira (MPB). As a young man, he had a vastly expanded tenor range and an angelic falsetto that regularly soared to breathtaking heights — a combination that led to his widespread recognition as a national treasure and once caused his collaborator Elis Regina to say, “If God sang, he would have the voice of Milton Nascimento.”

spalding’s dinner guests played her Native Dancer, the 1975 Wayne Shorter album that heavily features Nascimento’s vocals, serving as his first major crossover into the northern hemisphere. “You can feel the depth and intensity of everyone on the album’s musical mastery, but it’s like we’re hearing a new side of every player that’s influenced by Milton’s presence,” spalding tells me on a video call from her home in Portland, Oregon. “Part of what’s disarming about Milton’s sound is that he’s so confident and resolute in his gentleness. There’s not a lot of that register of male, particularly Black male, voice in the world that album comes from.”

In the ensuing 20 years, spalding would look to Shorter and Nascimento for inspiration in every area of her life. She joined forces with Shorter at the start of the COVID pandemic, writing the libretto for his final major work, the opera Iphigenia. Her newest project is a collaborative double LP with Nascimento that the octogenarian artist has indicated will likely be his last record. Titled Milton + esperanza, the album is dedicated to Shorter’s memory.

Nascimento sings in a different, less crystalline tonal register than he did half a century ago — his range has dropped about an octave and contracted significantly — but he still resonates on the same emotional frequency. “Milton could sing me a receipt, and I wouldn’t care,” spalding says. “The way he delivers it, the effect of his voice… It’s unlike anything else.”

esperanza and Milton met in 2009, when he came to her studio while traveling in Los Angeles during the sessions for her 2010 album Chamber Music Society. (She didn’t know it at the time, but it was Herbie Hancock who had alerted him to her work.) She went on to perform with his band at Rock in Río 2011 and began visiting him whenever she went to Brazil thereafter. “He loves to have his house full of people, not needing to do anything particularly — listen to some records, have a barbecue, whatever,” she tells me.

Still, it wasn’t until her most recent stint in Brazil that she finally began to feel comfortable calling him her friend. “In Milton’s case, that thing you feel in the music — this stoic, exquisite precision of meaning and sentiment — that’s how he is. But it took years of being around him to know that.”

The turning point in their relationship came when Milton’s son, Augusto, reached out to ask if esperanza would produce Milton’s next album: the project that became Milton + esperanza. She stepped into the role with the gravity and levity it deserved: Rather than impose her artistic paradigm on Milton’s world or attempt to conform to his, she came to the project self-assured in both her vision and her malleability. “I am what I am, and I don’t feel any need to pretend to be anything else,” she says.

The album is an astonishing portrait of a singular friendship, but it took a village to paint it. esperanza brought in heavy hitters from her jazz world — Shabaka Hutchings, Lianne La Havas, Elena Pinderhughes, Leo Genovese, Matt Stevens, Justin Tyson, Corey King, et al. — while Augusto and the album’s engineer, Arthur Luna, assembled an army of Brazilian legends from Milton’s generation (Guinga, Lula Galvão, Márcio Borges) and later ones (Tim Bernardes, Maria Gadú, Kainã Do Jêje), as well as the 31-piece Orquestra Ouro Preto. Other contributors include Milton’s longtime friend Paul Simon and Wayne Shorter’s wife, Carolina.

Stylistically, the album is a technicolor collage, blending swing with British invasion, spiritual experimentation with R&B opera, and neo soul with classic MPB. It’s a document of its time, place, and personnel, but also of the countless moments and souls that led to its creation, stretching back into eternity.

The FADER: I’m curious about your arranging decisions on the four renditions of older Milton tracks on the album. “Cais,” for instance, is pretty faithful to the original, whereas “Otubro” gets a much more radical reimagining.

esperanza spalding: When you’re a working musician, you’re on a lot of people’s projects; you go to that gig; you make that arrangement for somebody. At this point, after 25 years in music — woo, that’s so crazy — that step of strategic plotting doesn’t feel very important. What feels important is what’s giving me a charge. I’m trusting my gut to do that work, and that compass is what led me to the songs I chose for the record. I had to do “Cais,” and “Outubro” is one of my all-time favorite records.

I spent time with the songs, learned them, explored their harmonies, their feelings, their stories. I’d find a phrase, like, “Oof, that’s gotta be the meat of this segment.” And I trusted that once we saw all the parts together, it would be clear what we needed more or less of.

With “Outubro,” once we got into the studio and started playing it, I was like, “No, that’s not quite right,” so I was experimenting with other approaches, and I found the bass line. It’s a very relational, responsive process [that has to do with] the spirits of the folks I’m in the room with.

“There are lots of parallels with surgery: Your sound is literally entering people’s brains and their bodies. It’s vibrating their bones.”

Tell me more about that group. There are so many collaborators credited on this record, including a 31-piece orchestra. What was it like working with such a huge, shifting roster?

Again, it was all very relational. When we needed a musician in Brazil and I didn’t know them, my job as a producer was to research them, check out their stuff, talk to them, get a vibe, and make choices based on that. It’s like seeing patterns in the chaos, finding clear lines in a field of infinite possibility.

I love that work, especially the post-production part: “OK, we have 15 layers of texture. What do we actually need, and where?” I find the collaging [aspect] really satisfying, but I’m passionate about keeping the essence of what a person puts on a record, remaining true to the integrity of what they’re trying to say, even if I need to edit it.

Is it easier for you to edit other people’s parts or your own? Do you ever get precious or protective?

I treat everything carefully, but if something needs to go, it needs to go. Often, that thing I thought was cool is not actually cool. We’re making things that live forever, so I’m very disciplined about how I edit and what I leave on the canvas for all to see.

It’s a big responsibility. There are lots of parallels with surgery: Your sound is literally entering people’s brains and their bodies. It’s vibrating their bones.

Left: Milton Nascimento. Right: esperanza spalding. Photos by Pedro Napolinario.

It was Milton who chose the big English-language covers on the record, “A Day in the Life” and “Earth Song,” right? Were you surprised by those choices?

I was surprised by “Earth Song.” I was like, “OK, person who wrote ‘Travessia’ and ‘Tarde.’ That’s what inspires you? Cool, cool, cool.” That is not my favorite Michael Jackson song, and I remember thinking, “Ooh, it’s gonna be challenging to make this something I wanna play.” I love how it ended up, but I was a bit “Eek!” At first.

The old-timey chorus in your cover of “A Day in the Life” really surprised me. Where did that come from?

Leo [Genovese] was there, and he’s turned himself into a repository of so many eras and dimensions of jazz piano. Having him in the studio is really fun because you can go anywhere with him.

That middle section was our biggest concern because [The Beatles] are already playing with how corny it sounds. They’re satirizing a sound, and you can’t do a satire of satire, so I was thinking, “What’s the core energy of this moment? What if we do this crazy, untethered stride?” Nobody was gonna sing, “[snap] Woke up, [snap] fell out of bed,” so I said, “We just have to yell it. We have to untether.” That was the prompt for the whole song, and we went for it in every section we could.

“It’s like seeing patterns in the chaos, finding clear lines in a field of infinite possibility.”

Another song passage that jumped out at me was “Late September,” the interlude between “Cais” and “Outubro,” right near the beginning of the album.

“Late September” is my composite reflection on what I was immersed in while preparing for this record. I was thinking of “Outubro,” and I was thinking of Earth, Wind & Fire’s “September,” and how Milton had influenced them. If you put someone in a room and expose them to 15 different things, and when they come out, you’re like, “Say one sentence,” that sentence is gonna be a composite of all those influences.

I thought it would be a good entrée into the album because it’s a turning point. You meet us with “Cais,” which is about throwing yourself into this unknown journey. It’s like a sendoff, and “Late September” is the transition before you’re in the open ocean. We recorded it right before Shabaka stopped playing saxophone, and he happened to be in Brazil. It was such a special moment — maybe the final release with Shabaka on saxophone.

Photo by Lucas Nogueira.

You’ve dedicated Milton + esperanza to Wayne Shorter, and it closes with his composition “What Do You Dream?” Do you see parallels between your relationships with Wayne and Milton?

What can I say about Wayne? He’s everything. There are no words. He’s the genius — genius of spirit, genius of loving heart, genius of saxophone, genius of composition, of orchestral arrangements, of philosophy. He’s affected every part of my life.

I see why he and Milton were friends. Part of knowing Wayne is knowing there’s nothing you can do to emulate him. All you can do is be yourself all the way, go for broke. He used to say, “You can do something that makes a zillion dollars, and it doesn’t mean it’s of value. And you can do something that makes one penny, and it could be of infinite value.”

I thought about that with this record: It cost a lot of money, but I made sure its commercial viability was not the priority. Like, “We’re making something that’s gonna be in the world forever. Let’s give it the true essence of our connection and our joy and our silliness, and the rest will fall where it falls.” I’m already that way anyway, but I feel even more emboldened by how I saw Wayne, even at 89, living it so resolutely every day of his life.