The FADER’s longstanding GEN F series profiles the emerging artists you need to know right now.

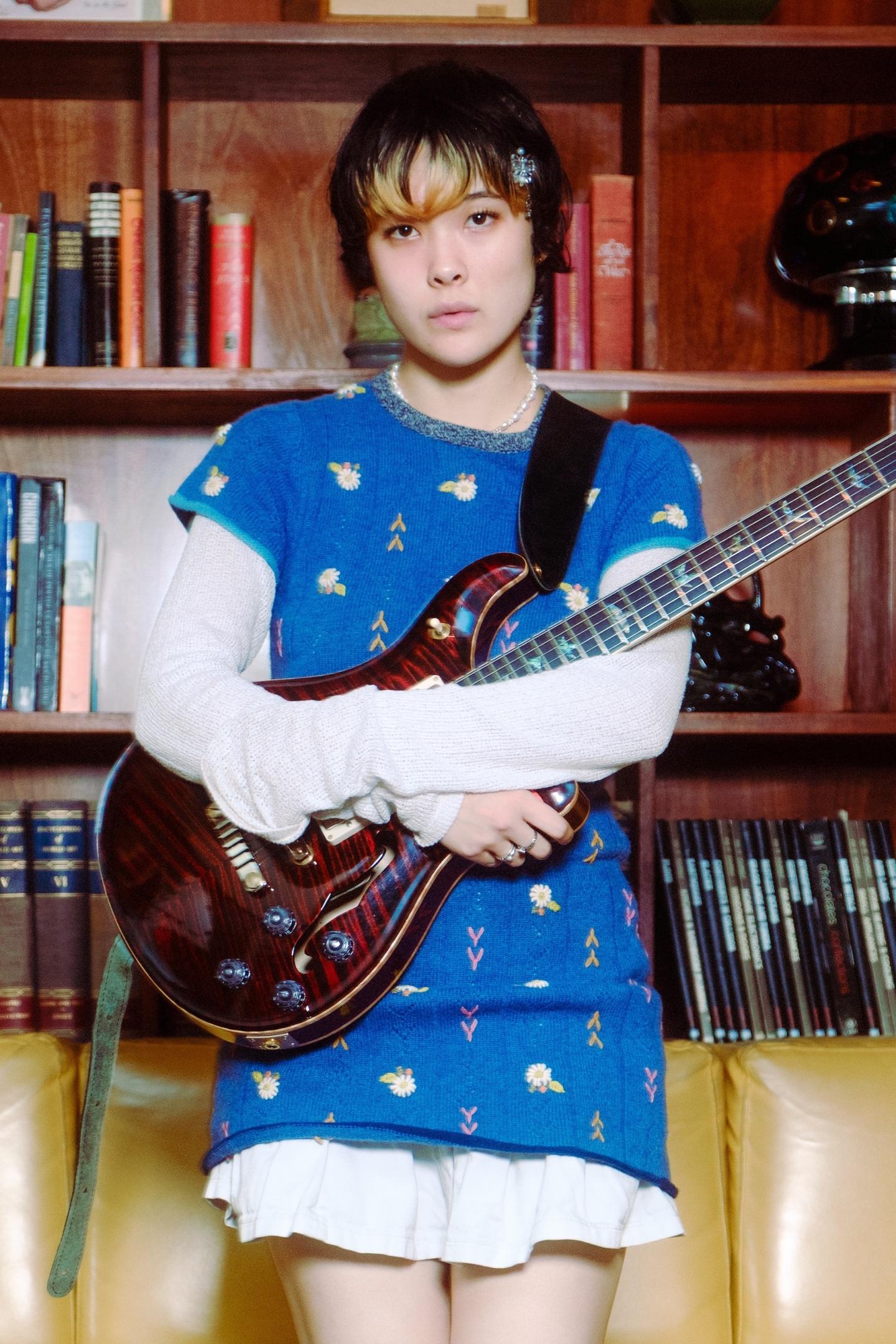

It’s Tuesday afternoon at Carousel, the only bar off the L train’s Jefferson stop with a velvet rope for the weekend crowd. The FADER’s photo shoot with Mei Semones has just wound down, but two other shoots start immediately after we sit down for our interview. Suddenly, the cavernous club is full of chatter. In our not-so-secluded booth, Semones’ soft-spoken aura stands out in contrast to the background noise.

At 24, Semones has the disposition of someone whose self-knowledge was hard won after years of feeling out of place. She brings this assuredness to her debut album Animaru, out May 2 via Bayonet. Japanese for Animal, it’s a record about learning to live instinctively after a quarter-lifetime mired in self-consciousness. “Everyone goes through phases of not knowing how to be a person, and there have been periods where I didn’t love myself in the way I do now,” she says.

Semones’ music has tacitly documented her rise to personhood. She says her first-ever single, 2020’s “Hfoas,” was the only song she’d written up to that point that she genuinely liked. Two key elements conspired to make this possible: First, she wrote half of the lyrics in Japanese, the language in which she and her mother have always communicated. “It helped me figure out who I am as an artist,” she says. “It felt natural to have [Japanese] be a part of my songwriting because it’s such a big part of who I am as a person.” Second, the song’s original version was a wordless Bossa Nova tune. A virtuosic guitarist since high school, she’d always felt more confident in her playing than her voice, but “Hfoas” was a turning point. “Realizing I could write something that starts as jazz but ends up pop,” she adds, “I was like, ‘Oh! I can do whatever I want!’”

Semones has been playing guitar since she was a pre-teen in Ann Arbor, Michigan, when watching Marty McFly invent rock ‘n’ roll in Back to the Future prompted her to ask her parents to let her switch from piano. As always, they were supportive: Her mother, an illustrator and graphic designer who’s drawn all of Semones’ cover art, encouraged her to forge her own path rather than following in the footsteps of others. And her father, a lifelong euphonium player, taught her the value of intensive, disciplined practice.

Semones’ high school taught jazz in small combos in addition to big band, and it was in these groups that she fell in love with the subtly brilliant guitar stylings of Jim Hall and Grant Green. Later, she’d find her true obsession, the pioneering Bossa Nova records of João Gilberto and Antônio Carlos Jobim. “Getz/Gilberto was my original inspiration to play that type of music, and it’s what I still listen to, over and over again,” she says. “I’m kind of lame in that sense.”

She wrote “Hfoas” halfway through her studies at Berklee College of Music, where she became even more attached to her instrument. On “Zarigani,” her new album’s penultimate cut, she compares the relationship to the one she and her twin sister share. “I love you like my guitar,” she sings. “I love you like no other.”

“Everyone goes through phases of not knowing how to be a person, and there have been periods where I didn’t love myself in the way I do now.”

“I Can Do What I Want,” track four of Animaru, starts off like an upbeat, major-key “Breadcrumb Trail” before diving headfirst into an upside-down world of smiling, splashy math rock. Like the majority of the album’s songs, it’s stylistically cohesive but tonally, rhythmically, and lyrically sprawling. And if the individual cuts largely stay within the loose orbit of their respective genre leanings, there’s no telling what will happen between tracks. Four Bossas — “Dumb Feeling,” “Tora Moyo,” “Zarigani,” and “Norwegian Shag” — thread through breezy lounge-pop (“Dangomushi”), whimsical walking-bass jazz (“Donguri”), and unabashed mathiness (“I Can Do What I Want”).

The album’s best songs are dynamic to the core. “Animaru,” the record’s thesis statement, is a quiet/loud declaration of independence from the pressure — factors internal and external — to label oneself. “I am not a cardboard box / Not to be lived in,” Semones sings as the track’s tension builds. When the hook hits its climax, she delivers the album’s most primal lyrics: “I am an animal / I live and I eat,” she belts in Japanese.

I ask her if she thinks non-human animals love themselves more than we do. “I don’t think they’re worried about it,” she says. “It’s just, ‘Am I hungry? Then I’m gonna eat. Am I tired? Then I’m gonna sleep.’” I ask her if consciousness is overrated. She stops to think. “When I see a dog, I’m like, ‘That seems so fun.’” She pauses again to reconsider: “I mean, maybe dogs are conscious; we don’t actually know. But it does seem fun to just exist, always in the moment. Wait… But then there would be no music.”

Moving to Brooklyn in 2022 sent Semones swimming from the pool of self-consciousness into the open sea of instinctual living. She says she finds it easier to live spontaneously in an urban environment full of exciting stimuli. The main change that’s helped her achieve her current mindstate, though, is the ability to pursue her craft full time.

Animaru closes with “Sasayaku Sakebu” (“Whisper, Yell”), on which Semones sings, “I will yell, this is my melody, it means something / It’s all I have, it’s everything / My melody, it means something to me.” Without a hint of sadness, she remembers times she was hurt, scratches on her knees and the bruises on her feet that no longer bother her.

“When I think about something bad that happened to me, or someone who hurt me, what makes me feel better is knowing I’ll have music for the rest of my life,” she says. “Whether I’m whispering it or saying it really loud, the message is still there.”