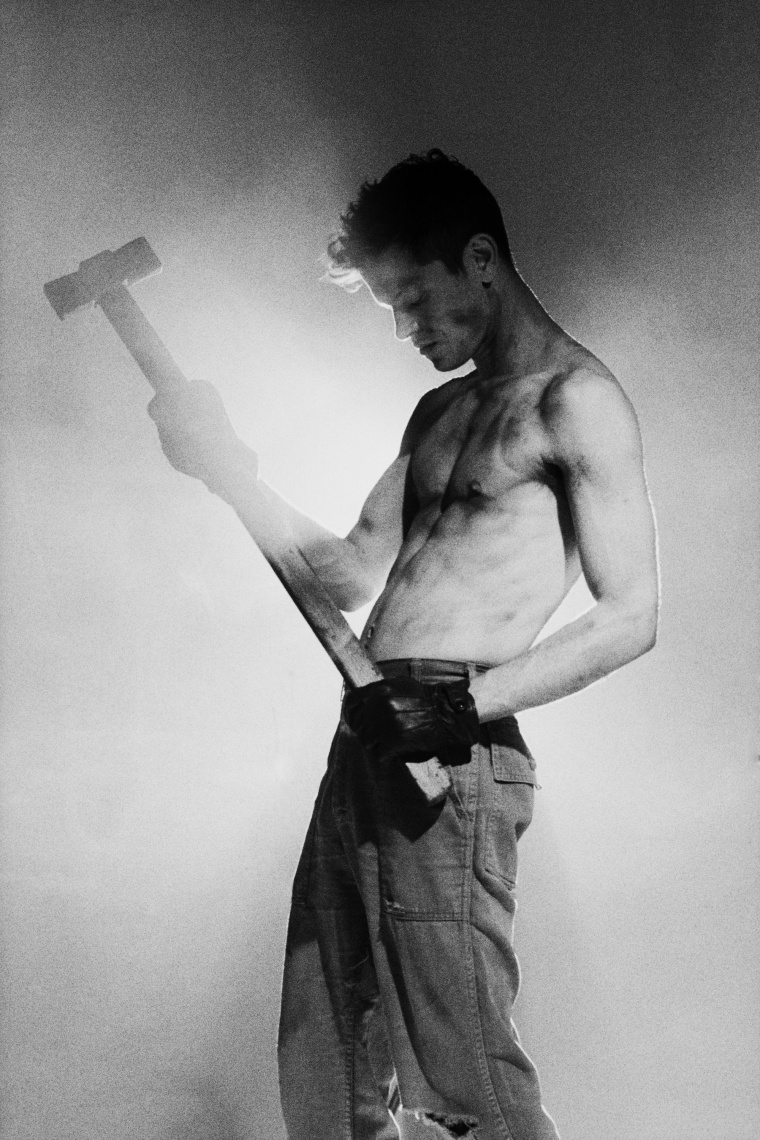

Majesty Crush in 1991

Amy Harlan

When Majesty Crush first started making music together they used two words to guide them: Covert (cool and quietly curious) and important (impactful and far-reaching). “We wanted our record to be the one that was on the turntable of people just like us,” Odell Nails III, the band’s drummer, says.

The Detroit band recently reissued its only studio album, 1993’s Love 15, plus a collection of singles, EPs, and rarities under the title Butterflies Don’t Go Away. They view the Numero Group reissue as an opportunity to celebrate the work of their late frontman David Stroughter and to wrestle back the narrative of being one of rock music’s sliding doors bands.

It is Stroughter’s lyrics, a meld of sex and violence that focused on characters living on the fringes of society, that still stand out to this day. While his peers were gazing at their shoes, Stroughter was conjuring a world in which danger and romance were bonded together. His songs depicted images of seductive adult store clerks and poisonous trysts. His bandmates, ravenous music fans, were bringing their love of hardcore, the psychedelic U.K. indie scene, and the emergent grunge sound, to create an equally dynamic backdrop to his noir-like visions.

“We didn’t sound like every other band who just wanted to sound like Nirvana,” says Hobey Echlin, the band’s bassist. “We embraced our limitations and ended up sounding different to everybody else.” And for a moment, in the early ‘90s A&R goldrush aimed at discovering the next Nirvana, they nearly made it happen.

The band formed in 1990 but had known each other for much longer. Nails and Echlin first played together in the ‘80s darkwave industrial band Spahn Ranch. When that group ended they took the chance to work with Stroughter (a school friend of Nails) and recruited guitarist Michael Segal, who they knew as the guy who would recommend them music by A.R. Kane and other obscure but life-altering albums from his job behind the counter at the local Play It Again Records. Segal had never played guitar before and turned up to the first practise, where they attempted to nail a cover of New Order’s “Blue Monday,” with just three strings on his instrument. There was another, far more proficient, guitarist who wanted to join but they picked the cool guy from the record store who couldn’t play a note. “It told me which direction they wanted to go in,” Segal laughs.

After playing their first show as openers for Mazzy Star, Majesty Crush found themselves immersed in Detroit at a time when the hardcore, indie rock, and techno scenes were all thriving. “The idea that anybody can do anything if they believe in the music came straight from there [Detroit],” Nails says. “We would go to The Music Institute after rehearsal because someone knows Derrick May and he’s doing a set. Detroit never had a whole lot of segregation when it came to underground culture.”

As Black men, both Nails and Straughter stood out in the overwhelmingly white world of ‘90s guitar music. Stroughter’s father was a US serviceman who married a German woman while stationed in Europe. They relocated to Detroit and enrolled their son in a middle class suburban school where Nails was a student. The two kids bonded over music and, as Nails tells it, didn’t think too much about their backgrounds. “It’s more apparent to me now, frankly,” he says. “It was special and super rare for there to be two people of color involved in this world.”

If anything, Majesty Crush saw themselves as outsiders by virtue of being “anti-machismo” at a time when grunge was entering the mainstream and things turned plaid and a little boring. “Our audiences were young, passionate, and tapped into something emotional and feminine,” Nails adds. Echlin agrees. “We wrote songs you’d listen to in a cold room on a depressing Sunday evening,” he says with only a slight self-deprecating tone.

Early singles “Sunny Pie” and “Grow,” both of which feature on Butterflies Don’t Go Away, capture that soft melancholy vibe nicely. “Sunny Pie” is a hypnotically pretty depiction of a relationship that pushes boundaries. “I remember when we went out,” Stroughter sings like an angel before flicking up his horns. “You’d order for me, then dress me in your lingerie.”

“Grow,” meanwhile, feels like being swept off your feet by feedback and noise, something at which the band were expert. Majesty Crush can be found on plenty of shoegaze playlists right now, at home alongside icons My Bloody Valentine and newcomers like Glixen and They Are Gutting A Body Of Water. With their swirling guitars, dreamy vocals, and cavernous production it is easy to understand why they have become a favorite among both shoegaze crate diggers and new converts.

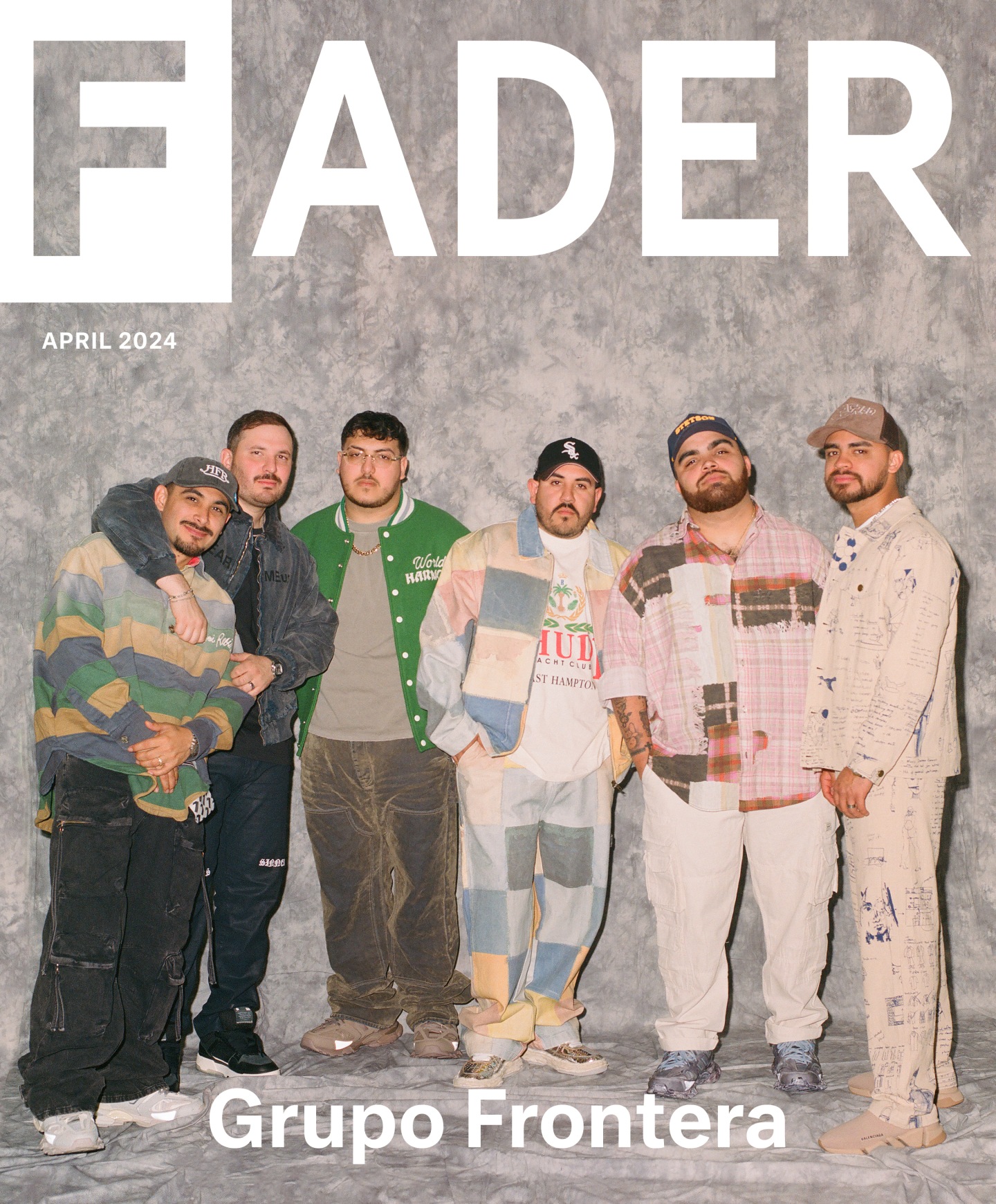

Majesty Crush (L-R) Hobey Echlin, Michael Segal, David Stroughter, Odell Nails III.

Carrie Kelly

Shoegaze has been cresting through indie rock circles for the past couple of years, taking root in both vinyl collections and on TikTok and Discord channels based around primarily online artists including Jane Remover and South Korea’s Parannoul, whose music has become progressively more analog as they have developed. What once felt like a genre consigned to the past has been reborn as people seek escape in the dream-like atmospherics and the physicality of maximalist and incredibly loud production style.

While Majesty Crush are often grouped in as part of the resurgent genre, however, they don’t feel their music really belongs as part of the scene. “We had a dedicated frontman,” Echlin argues. “It wasn’t all pedals and obscure lyrics. We had a guy stalking the stage and getting in people’s faces.”

Stroughter’s ability to provoke and paint uncomfortable images is perhaps best captured in “No. 1 Fan,” the band’s 1992 breakout single. Written a decade prior to Eminem’s “Stan” and even further before the rabid fandoms of the social media era, “No.1 Fan” is a portrait of an obsessive follower; the kind who would stop at nothing to get close to their idol. “I’d kill the president for your love,” goes the chorus to the song inspired by John Hinckley Jr.’s crush on Jodie Foster and his 1981 assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan, designed to win the actress’s attention. Like so many of Majesty Crush’s songs, the inextricable links between sex and death are laid out in blood-spattered prose.

While his lyrics and stage presence were a captivating force, Stroughter, who was diagnosed as bi-polar at 27, struggled with mental health problems. He could be challenging to work alongside. Nails speaks of someone who always pushed his bandmates and took “confrontational cues” from his own hero, The Doors’ Jim Morrison. The drummer recalls one night when Stroughter, having just read Morrison’s autobiography No One Gets Out Of Here Alive, decided the true purpose of that evening’s show was to start a riot. “He was not a traditional thinker,” Nails admits.

Segal is more to the point. “Dave was a sweetheart to be around until he wasn’t,” he says. “We would turn up to our rehearsal space after a day of work and he’d have been there all day scheming about the band and stewing. He could be a son of a bitch because he was so intense about what we were doing.”

“No.1 Fan” was released in 1993, the year after Nirvana had put out Nevermind and inadvertently created a frenzy of music industry attention on the alt rock scene. Bands were stumbling into major label deals and Majesty Crush were no different. They signed with Elektra subsidiary Dali/Chameleon, making them labelmates with Lucinda Williams and Josh Homme’s early band Kyuss. They entered the studio to record Love 15, graduating from working with local hardcore producers to playing instruments last used by the Doobie Brothers. The record includes great songs like the soaring anthem “Cicciolina” and “Penny For Love,” a jangly pop song written after Stroughter was locked up for two nights having been falsely accused of an armed robbery. There was an energy to the time that, they recall, felt momentous.

The band were faced with disaster, though, when just one month after they released Love 15, they were informed that Dali/Chameleon was being dissolved by its parent company and they were, effectively, homeless. Negotiations to have Moby remix a song on the album were abruptly dropped.

Majesty Crush were dented by the setback but refused to be defeated. They continued touring and released the Sans Muscles EP in 1994, though even that title suggested the end was in sight. “Muscles” was Echlin’s nickname for Stroughter, a weightlifter in his spare time, who had quit the band shortly before it was released. The EP feels like a curtain coming down on a childhood dream that briefly flirted with being something spectacular. “If JFA Were Still Together” stands out not just for its liquid bassline and jet engine level levels of noise, but also Stroughter lamenting, “They used to have a cause, them against whoever.” Thirty years on it feels like a bittersweet acknowledgement of defeat.

One of the long-term effects of being dropped, Nails says, was Stroughter adopting an “ultra-aggressive desire to be a rockstar.” Having felt that Majesty Crush had done everything right, just to become collateral damage in a corporate restructure, he doubled down on his swaggering, riotous side. “It hurt him to the core,” he says of a friend he watched drift out of his life as he chased some form of redemption.

Stroughter followed many paths post-Majesty Crush; he worked as a presenter for MTV, moved to Los Angeles, recorded solo material as P.S. I Love You, and would flip vintage cars at auction when money was low. His ability to access medication during such periods of economic instability made for a precarious situation and, tragically, Stroughter was shot and killed by police in 2017. The Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office investigation into his death revealed he was shot by police after threatening officers with an ax. The judge concluded that the multiple officers who detained their firearms used reasonable force in self-defense. Stroughter was 50.

The remaining members of Majesty Crush hope that the release of Butterflies Don’t Go Away will revive the stories their beloved former bandmate wrote and the unique world he ushered people into with his music. They speak of a frontman who lived to be heard and who would be reveling in the newfound focus on the band from a new generation of fans discovering them online. They remember endless laughter in the early days of the band and the beacon of creativity they lost when he passed. The story of Majesty Crush and Stroughter are both ones of lost potential and moments of pure devastation. With the re-issue of the music they made together, Nails, Echlin, and Segal hope they can at least give one side the ending it deserves.

“We all thought we were a pretty good band back in the day,” Nails says modestly. “We had a break that didn’t end up well but I knew we had music that needed to be heard. We were just on the precipice of that happening and then it got taken away. Vindication sounds way too negative, but this moment feels deserved.”