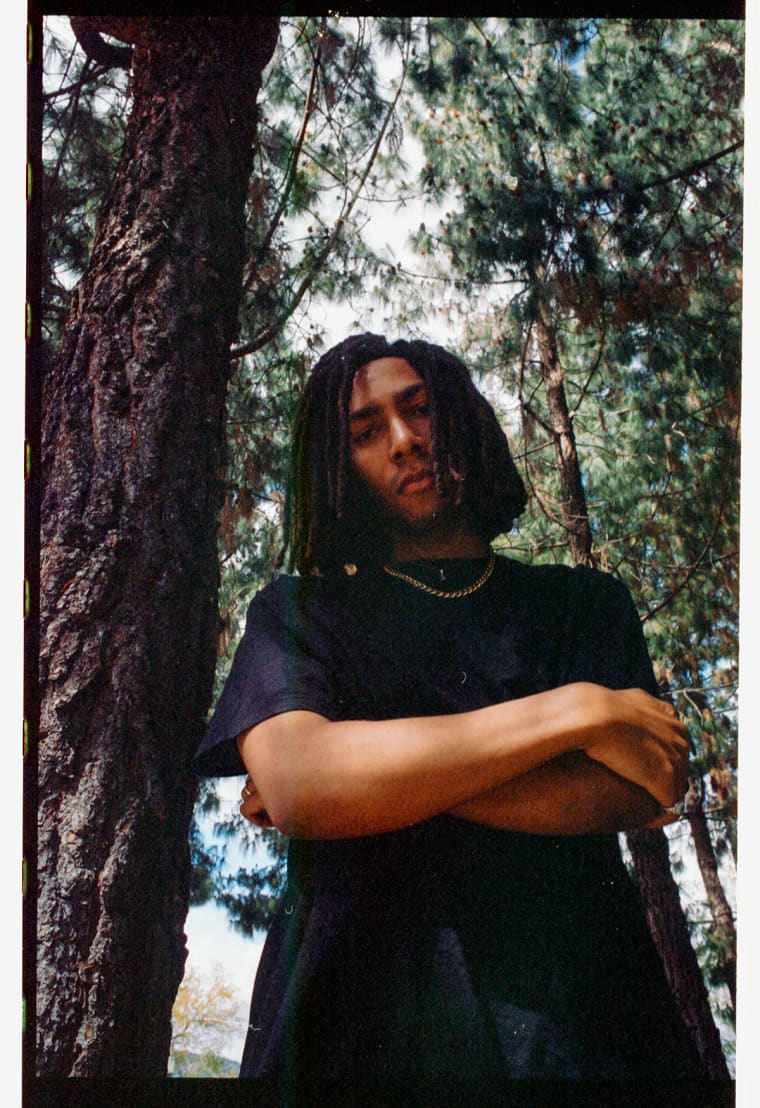

Lutalo. Photo by Adam Alonzo

Story-truth — or emotional truth — is just as significant and meaningful as what’s real. On Lutalo Jones’s debut album, out September 20, the 24-year-old Minnesota-raised, Vermont-based musician approaches the concepts and ideas they weren’t able to understand as a child through songwriting and memory, carefully filling in the gaps of what they found difficult to process and revisiting their earlier experiences as an adult.

Named after the prestigious private school that Lutalo attended on scholarship in St. Paul, Minnesota, The Academy draws inspirations from lo-fi, slacker guitar acts like Mac DeMarco and Palehound and The National-oriented indie rock, with an added dose of weirder, experimental post-punk and Big Thief-inspired folk.

Lutalo’s verses are descriptive and grounded in place and setting, both emotional and physical, and read almost as tightly-written poems or succinct vignettes of prose. Lutalo takes on the role as narrator in their music, playing with auto-fiction to blend elements from their own childhood with fiction. In opening track “Summit Hill,” Lutalo recalls revising the grounds of their former school with a friend, surrounded by the grand brick houses feeling a sense of wanting to have a sense of home that felt as strong and grand as some of those places, too. In the Schoolhouse Rock-inspired, Kurt Vile-esque “3,” Lutalo describes the onset of anxiety as it literally suffocates him, the metaphor of asphyxiation evolving into feeling as if a noose is around his throat: “On my own, I’m a little tied up… around my neck, I’m a little tied up.” Across the record, Lutalo’s drawl is assured, introspective, self-reflective and coming from a place of intuition, all while still questioning the world around them.

The Academy deals with Lutalo’s recollections of their family losing their house when they were nine years old during the 2008 financial crash, and what that meant for their family and future. It was a turning point, a hardship that incited their life-long contemplation of societal inequality and division, while also understanding the importance of acceptance as they challenge themselves, using music as a way to process their upbringing.

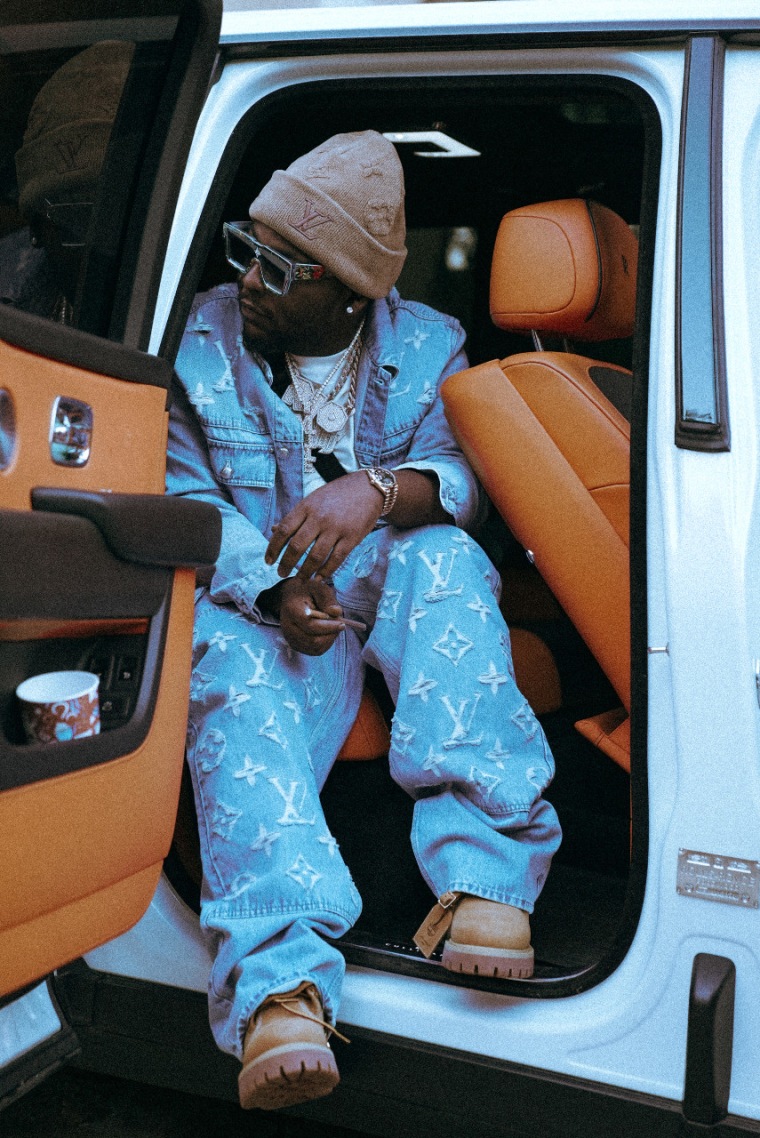

Photo by Adam Alonzo.

The FADER: What made you decide to focus on your time at The Academy in particular for this record?

Lutalo: The Academy is about school, but also the academic observation of living from childhood up to this point, so everything that I experienced, for the most part. I try to look at it from an academic perspective. I wanted to be able to lay a groundwork of something for people to be able to build narratively. I viewed that as my prologue; my introduction to what this world is. I’ve been labeling this as the first chapter or the beginning of a story that I plan to continue to tell throughout future albums, and that these will all be connected in certain ways.

I love how you talk about your music being chapters, and using literary themes to narrativize your art — it’s like you reorient your perspective the older you get, and try to view your upbringing through a more holistic lens through intellectualizing what you didn’t understand. How do you approach writing?

I would say the instrumental informs a lot of lyrical content. I mostly focus on feeling and emotion first. That’s usually what inspires the first spitting of words, which often is this mumbling that will eventually be chiseled away. Maybe that’s a better way of looking at it. It’s chiseling away at stonework and discovering what it means later on, somehow. That’s why I like to play into this concept of magic. We get to a place where it makes sense. There’s indicators and random words that come up first. Sometimes, I don’t know what the song is about until it’s over.

I’ve always liked fantasy stuff. I was really into anime. I’m still into anime. One of my favorite anime is Soul Eater, and they have a lot of characters and world-building that I think is really cool. Naruto was a big one when I was a kid. I always played games and video games with my friends. We’d have a really great imagination.

There was a shift, obviously, as I was growing up, where I tried to hyperfixate on pragmatism, and what was real. It’s just romanticizing things and shifting my perception.

Photo by Adam Alonzo.

Photo by Conor MacCormack.

It’s all based on feeling.

Yeah, mostly feeling and intuition. I think the best literary work is able to speak to people based on how deeply it connects with your personal truth.

I would say a lot of your lyrics are kind of in the stream-of-consciousness realm, but they’re also succinct. In “Ocean Swallows Him Whole,” for example, there’s a lot of tangible imagery that elicits feeling: the fog, the ocean, the melted wings. You mention blue to evoke sadness, loss. But you take a lot of care to not ramble.

There’s a part of it that is definitely a stream-of-consciousness, and then there’s points where I’m like, “The song is telling me that I need to say this word” or “This needs to be how we end.” Sometimes, I listen back to songs that I’ve put out and I’ll be like, “Oh, I misheard the lyric. It’s supposed to be … this other word.” It made me learn how to listen to your inner voice.

I think the best literary work is able to speak to people based on how deeply it connects with your personal truth.

There’s a lot of range within genre across this album –– I hear a lot of early Bloc Party and some weirder King Krule influences, all tied together by guitar-based indie rock like The War on Drugs. How’d you get this sound? What did you grow up listening to?

My dad was a hip-hop head… sharing a lot of A Tribe Called Quest, and then I also ended up discovering a lot of rock music.

Coldplay was probably the easiest one at that age — Parachutes. A lot of bossa nova, jazz, Miles Davis [too]. I remember early Kanye. Later on, in high school, I really discovered what indie music was from watching Scott Pilgrim and being like, “What is this fucking cool, gritty-ass sound?”

Would you say your lyrics are written from an auto-fiction point of view?

I suppose so. Like Scott Pilgrim is not a real person, but he represents a real type of person and all those characters represent real people. I’ve just made Lutalo as another one of those characters. I’m living as Lutalo, and I also get to shift and build how I perceive Lutalo to be.

Do you have a preference for writing music versus writing lyrics?

The music part is a lot easier for me. For a long time, I honestly didn’t listen to lyrics. I was focusing on just how music made me feel. My brain wasn’t able to register lyrics very well. It wasn’t until later in high school that I started to really listen to lyrics.

There are points where I’m like, “The song is telling me that I need to say this word” or “This needs to be how we end.” Sometimes, I listen back to songs of mine that I’ve put out and I’ll be like, “Oh, I misheard the lyric it’s supposed to be, and it should have been this other word.” It made me learn how to listen to your inner voice.

I’ve just made Lutalo as another one of those characters. I’m living as Lutalo, and I also get to shift and build how I perceive Lutalo to be.

What was on your mind when you wanted to write “Big Brother”? It’s a heavy song.

“Big Brother” is about a couple of different things, simultaneously. It’s about growing up with my younger brother and our relationship. We are very close now, but I remember when he started high school and I was like, “Dang, I pushed my brother away. That’s sad.” And maybe it wasn’t as bad as I think it to be, but I like to reflect on it, as an older sibling.

The other side of it was growing up during the 2008 housing crisis. We lost our house during that time. I was probably eight or nine and trying to reflect on what the hell was going on. My dad was usually pretty good with explaining what was up to the best of his ability.

It was just such an odd concept that now we don’t have a home. It’s mostly things that I was witnessing and observing, and then trying to capture what it felt to be confused, but also putting things together slowly and being like, yeah, this stuff is happening, and someone [else] is coming out on top.

How much were you able to understand at such a young age?

There were points where things were really intense, and I did ask questions. My dad would try to give the most age-appropriate answer for why certain things were really ingrained into our lives, like the military industrial complex. We’re not for that subjugation of Black and brown bodies. We’re not for that war-mongering. I remember there was a time when my father was like, “What’s going on with our family is an unfortunate situation,” and I just accepted that. I applied that to my entire outlook.

Photo by Adam Alonzo.

Did you find yourself questioning a lot, when you were younger?

Since I just accepted things, there were plenty that I didn’t question. There were moments where I was like, “Dang, I haven’t really processed all of this.” And that was what this album was supposed to be for myself as well. My dad’s mentality was basically, “I’m going to arm you with how people are going to shift, how they communicate and engage with you as you continue to age as a Black person.” Like, hey, the way that these people talk to us, be mindful of that. The way you’re looked at on the street, be mindful of that. When you’re in this neighborhood, be mindful of how you’re being perceived.

It definitely prepared me for a lot. It probably made me a little jaded at such a young age, and maybe that’s just what it is.

My mom did a similar thing where she would try to hide the complete truth for me when I was younger, as a mode of protection. But kids are a lot smarter than people think. I would rather just know. There’s a way to deliver information that is empathetic and kind.

I understand that. It makes you feel like a child, basically. My dad had a lot of moments where his perspective was just like, “I won’t lie to my children.” There was no Santa. There was no Easter bunny. It was him. He was doing shit. There’s also another side to it where it’s like, “Oh, I missed out on some of the magic and that’s what I’m trying to recreate within my current life.” I think that truth is trusting that your kids are smart enough to be able to process things. There’s a time when information is good and there’s others where it’s really not helping anything. I don’t think he got it right every single time, but you do your best as a parent.