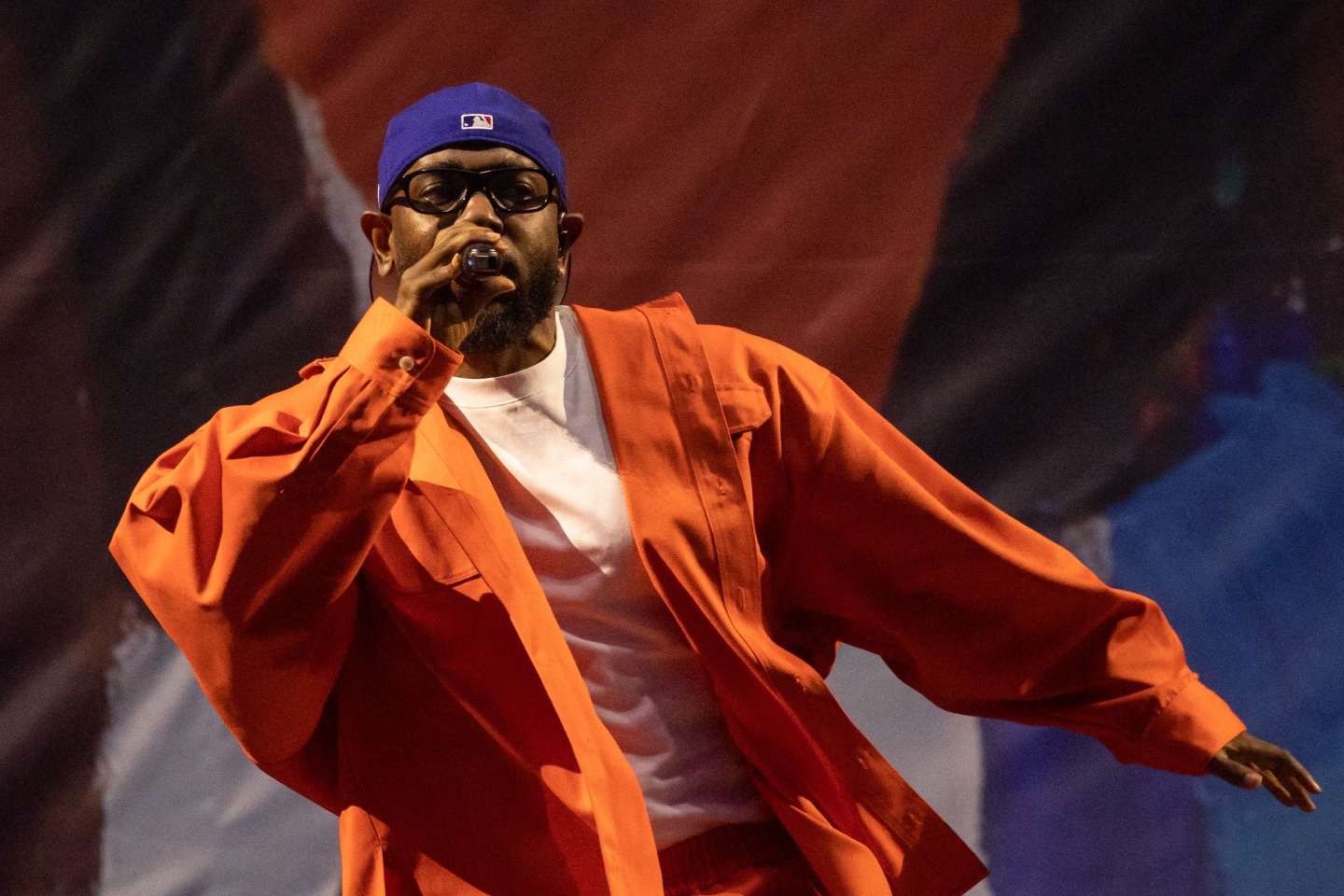

James Massiah. Photo by Will Wright

Apollo Frequencies is a series exploring sounds that seem to come from another world. In this week’s edition, James Massiah (aka DJ Escrow) discusses how he freed himself from humanity’s laws in the making of his debut LP.

James Massiah grew up in the Church. Raised in south-west London, he played drums as a teenager, touring the city’s extensive circuit of Seventh-day Adventist congregations. “It was the harmonies that got to me — the haunting sounds in minor chords and how they changed when there was a shift to darkness,” he tells me on a video call a few weeks after the release of his debut album, Bounty Law. “I loved that sense of longing or pain you could get with certain notes and intonations.”

He started writing poems as soon as he could read. For his sixth birthday, his mother bought him a copy of A.A. Milne’s Now We Are Six, and he remembers mimicking those poems in his earliest work. As a teen, he was drawn to the grime and road rap he heard on pirate radio but saw hip-hop as a world completely separate from his own. “I didn’t think of what I was doing as rapping, but I did enjoy the fact that MCs like Dizzee Rascal were playing with language, and I wanted to do that too,” he says. “It was only as an adult that I started to see less of a binary between the two.”

Since leaving the Church at 18, Massiah (now 34) has broken boundaries imposed on him from within and without: the institutional taboo on sexual desire that had caused him endless angst as a teen, the mind-body barrier (via psychedelic substances), the gulf between poetry and partying — his Adult Entertainment series pairs readings with afters powered by dancehall and dub — and, most recently, the social contract. “I had so many limitations in the Church, and then I was lawless,” he says. “Now I’m putting down my own rules.”

James Massiah. Photo by Will Wright.

Massiah first dabbled in rapping in the mid 2010s, when legendary London recluse Dean Blunt recruited him to play the exaggerated role of a road rapper in his Babyfather project. A fan of Massiah’s poetry and his deep-cut DJ sets, Blunt connected the dots between these skills before Massiah could. “It just goes to highlight [Dean’s] genius,” he says. “Like, ‘Here’s this person. They do this, they do that. I see an angle where they can exist in this world I’m creating.’” He’ll be reassuming the role soon, he adds, smiling when I ask him if there’s more new music coming in the wake of “bluey vuitton,” Babyfather’s 2024 collab with producer-of-the-moment evilgiane.

On the urging of friends and against his own best judgement, Massiah dropped his first solo tape, Natural Born Killers, in 2019. He was much more confident in its follow-up, 2024’s True Romance EP. Returning to road rap, he mined the dissolution of his last few love relationships over stripped-down, dubby beats. “It’s less about breaking other people’s hearts than it is about me breaking my own heart and coming to terms with the ways in which my upbringing and relationship to sex have impacted my ability to perform the role of a partner,” he says. “I was immersed in this world of drugs and hedonism, and I wish I could’ve communicated better that I had to go through these things to figure myself out.”

Bounty Law is about the freedom that comes when one renounces conventional relationships, romantic and otherwise. Employing outside producers for the first time, Massiah raps above dream-dusted beats from the perspective of a modern-day outlaw. This freedom comes at a cost — even on the record’s slickest, most swaggering cuts, our hero grieves the life he’s leaving behind — but it’s worth it in the end, at least for now. Unshackled from social mores, he’s ready to be the ruler of his own free world.

The FADER: You’ve framed Bounty Law as a Western set in London.

It’s not meant to be a literal Western, but I like the idea of outlaws and cattle rustlers going back and forth across county lines, shootouts, people running into the saloon, getting drunk, having a fight. I’d been running around town quite a bit, and it felt like there was no regulation, like anything was possible in quite a scary way. I realized I was gonna have to be the sheriff of my own life.

I was thinking about the idea of the outlaw in a world where it’s everyone for themselves, where the price of success is the bounty on your head. How much is it gonna cost you to get what you want? What are you willing to pay for happiness and peace of mind?

If this was a Western and you had to make a character chart for its protagonist, what would their most important traits be?

The character is like any tragic hero, the kind that you have in [the films] Natural Born Killers and True Romance, even Django Unchained (I named the last two projects after Tarantino movies, and I often go to him for references when I want some creative direction). [The character is] trying to figure it out, get it sorted, make sense of the world they’re in. They’re trying to score, but there’s a question they can’t answer.

The track “Baby” is like, “We could take over the world, me and you, if only you’d let me know if you want this or not.” And “Peroxide” is letting go of that dream, like, “You know what? I can go anywhere in the world and find what I want. It’s up to me to decide.” It’s the social contract moving from collective responsibility to individual responsibility, which you see in action films. The album could’ve been called The Bourne Identity.

While I’ve got this passion, I want to use it ’cause I don’t know how much longer I’ll feel this way.

My reading of the story was cyclical, starting and ending with these hedonistic benders that seemed destined for disaster, rather than linear, like the hero’s journey you describe.

A lot of the record is about one particular relationship that was really sour at the time. It starts with “Pop Down,” where I go home after I’ve been out partying, and we have a fight about where I’ve been and who I’ve been with. By the end of it, I’m like, “Look, should we just get married and have a baby?” And then [“Peroxide”] is like, “Well, if we’re not gonna be clear on that, then I’m just gonna go out into the world. I’ve got things everywhere, life is good.” That’s the end of the album, but then it’s like, “Oh, I kind of want to see this person,” and we pop down again. I’m keen to get the next record out because I feel like I’ve already broken out of that cycle with that person. I’ve gotten better at communicating what I want and what I can offer. I’m more confident and more brave.

This is the first time you’ve had other people produce one of your records, and a lot of the producers you chose are part of your scene. Who do you see as your peers in London right now, and how did that scene contribute to the way the album sounds?

Jawnino and sasha B have worked with most of the producers on Bounty Law — 3o, Cajm, and Cold. I had my own relationship with those producers before that, but it was through hearing the music they made with Jawnino and sasha B that I was like, “Wow, I trust you. You’ve done so well in carrying and containing the power and essence of what sasha B and Jawnino want to say with their music that I feel like you can do the same with mine.” They all know my production, and they honored it in their own way.

It feels so good to be in this mix of artists I respect and admire, and I want to say more and do more and travel more. I want to keep the momentum up. While I’ve got this passion, I want to use it ’cause I don’t know how much longer I’ll feel this way. I’ve got access to producers who respect and love me, and friends who have studio space and let me take advantage of that. And there’s an audience who wants to listen, so I want to keep feeding and respecting them as well, rather than waiting another five years.