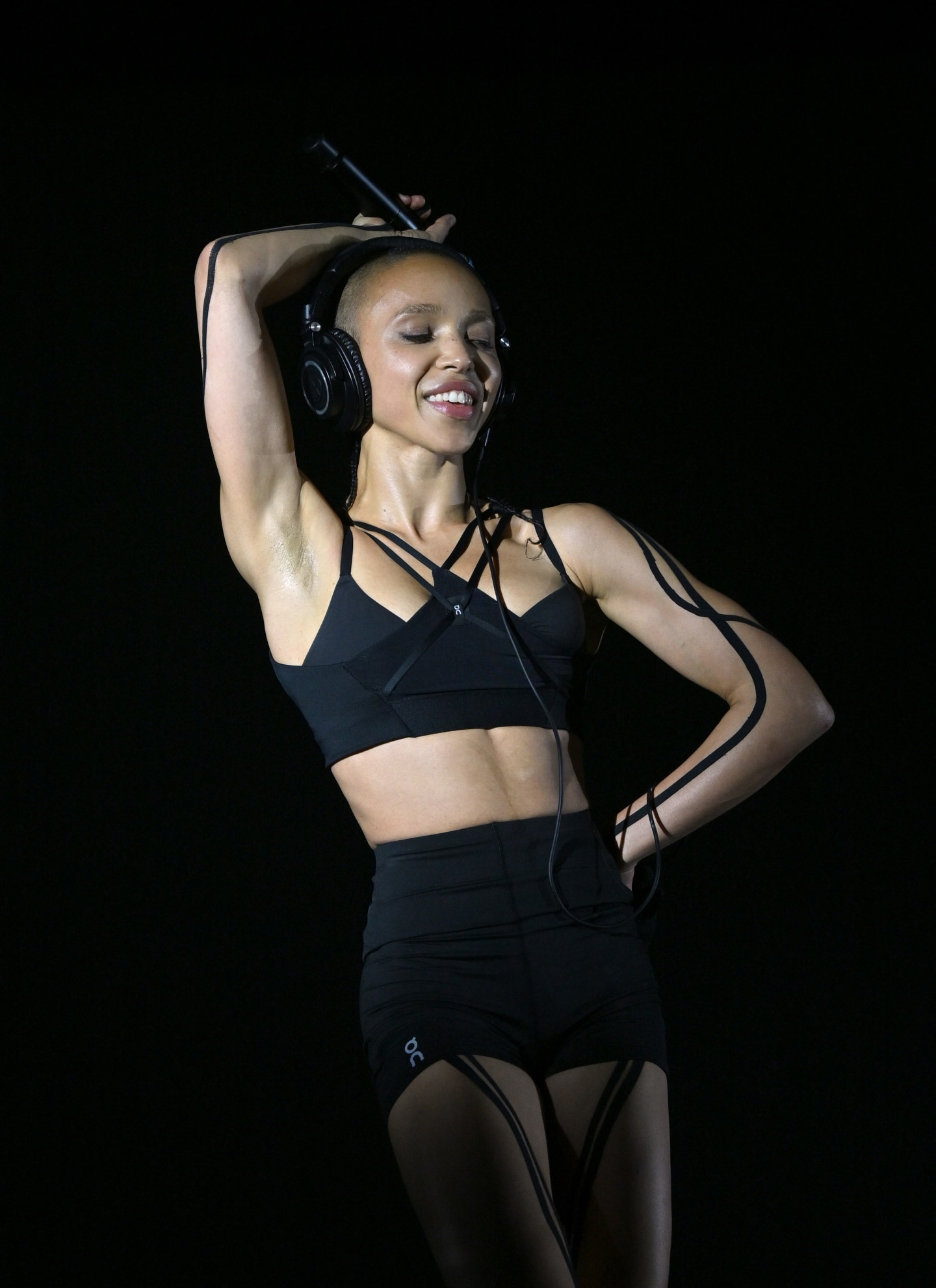

FKA twigs. By Dave Benett

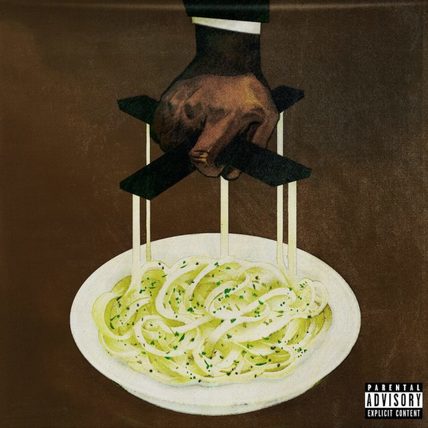

“Eusexua” is not just a word but a philosophy created by FKA twigs to describe the deep and intimate feeling of what happens to your body when you connect to a piece of art, or maybe another person. A combination of “euphoria” and “sexual,” it’s what happens when “you’ve been kissing a lover for hours and turn into an amoeba with that person,” twigs told British Vogue. “You’re not human anymore, you’re just a feeling.”

It’s with this mentality that I went to the EUSEXUA rave at Brooklyn’s The Chocolate Factory on October 19. Hosted by fantasy and Unter, an infamous NYC-based techno party series, it was the third of a series of sold-out parties that twigs has been hosting in anticipation of her new album’s release, due out January — and was expected to be one of the season’s most exclusive social events. The first two “Scorched Soil” raves, held at London night club The Cause and Los Angeles’ The Reserve in September and October, encouraged nude tones and textureless regalia, and the theme for the Brooklyn rave again pushed the need for skin-toned attire. When I received my invite, I was notified of the strict dress code: “An unearthed nude expression birthed upon scorched soil and steel….” Whatever that meant, I knew I had to take my job seriously, as both an FKA twigs fan and a journalist.

I borrowed a cream Rick Owens tank top and bottoms from my roommate, since I owned nothing in the color of “scorched soil and steel” (and thankfully, she, also a die-hard twigs fan, understood how crucial it was for me to follow the philosophy of the rave). I also packed my DLSR camera, a notebook, and a pen. I wasn’t sure what my coverage would entail; my instinct was to photograph rave-goers, document the night with some video footage, and talk to people on the dancefloor about what “Eusexua” meant to them.

When I rolled up to the venue just after midnight, I was shocked to discover that the line was already 200+ people deep. Though my initial fears were about my camera being confiscated, since I had not been granted a photo pass, I quickly realized I faced a more pressing problem: not being allowed in due to my outfit choice. The fashions of my fellow line waiters were astounding: beige leather bondage; skin-tight, nude-toned leotards; sheer tulle miniskirts; coffee-colored bra tops and matching panties (with the exception of one influencer in front of me who was in a Harley Quinn-esque outfit with black platform Crocs). The common idea, I was now belatedly realizing, was to dress in as little clothing as possible to allow for freedom of movement, expression, and ultimate skin-to-skin contact. I felt self-conscious standing there in my loose pants and long coat; I was too concerned about how my clothes would look instead of being aware of how they might make me feel. But my concerns were eventually for naught; after an hour of waiting in line, I’d entered the warehouse, my outfit in the clear.

The Chocolate Factory, situated just a stone’s throw away from Elsewhere, is the kind of sprawling, underground-rave venue full of corridors, hidden rooms, and plenty of hiding spots where faces and voices get lost in the darkness. There were no intricate decorations, or visualizers, just lights that flamed in the shades of human flesh — orange, red, green, and yellow — matching the beat of the DJ set. The largest portion of the venue, housing the main dancefloor and the DJ booth, was a pulsating organism of indistinguishable limbs, heads drawn together in kisses, hands and arms intertwined, and bodies flexing and shifting in dance. I gravitated towards an empty corner, getting prepared to photograph the moving mass on the dancefloor. But my presence seemed to repel the rave-goers as they steered clear of me and my Canon. Nervous, I forced myself to raise my camera to a photograph of a couple locked in a tight embrace just a few feet away from me. One of them looked up, stared at me dead in the eye, frowned, and made a slashing motion across their neck. Moments later, security tapped me on my shoulder, prompting me to relinquish my camera until the end of the night. I gladly obliged.

Without my camera, I tried to lose myself in the experience. For FKA twigs’s short set, she played three cuts from the album: the already released title track, the latest single “Perfect Stranger,” and unreleased song “Drums of Death.” During the brief period she was in our presence, the club swelled with frenzied emotion and hysteria. Phones were out and about in abundance, of course, as twigs’s disciples frantically tried to document their encounter with their deity — which seemed to miss the point. Really, all they should have done is what they’d been doing up until that point: dancing and holding one another.

As Dr. Rubinstein, Young Male, and Meilgaarden kept the party going, I realized that in my attempt to document what EUSEXUA looked like I had disrupted its very ethos; to witness EUSEXUA is to feel it yourself. I had no photo pass because this was a space not meant to be photographed.

Just before sunrise, I left the warehouse with my camera stored safely in my bag and my phone still set to Do Not Disturb. I didn’t use it for anything other than listening to “Perfect Stranger” on the train ride home, thinking about my clothes, now glistening with the sweat of other people’s bodies. I thought about the last pair of lips I kissed and how no photograph or piece of writing could ever replicate that euphoria.