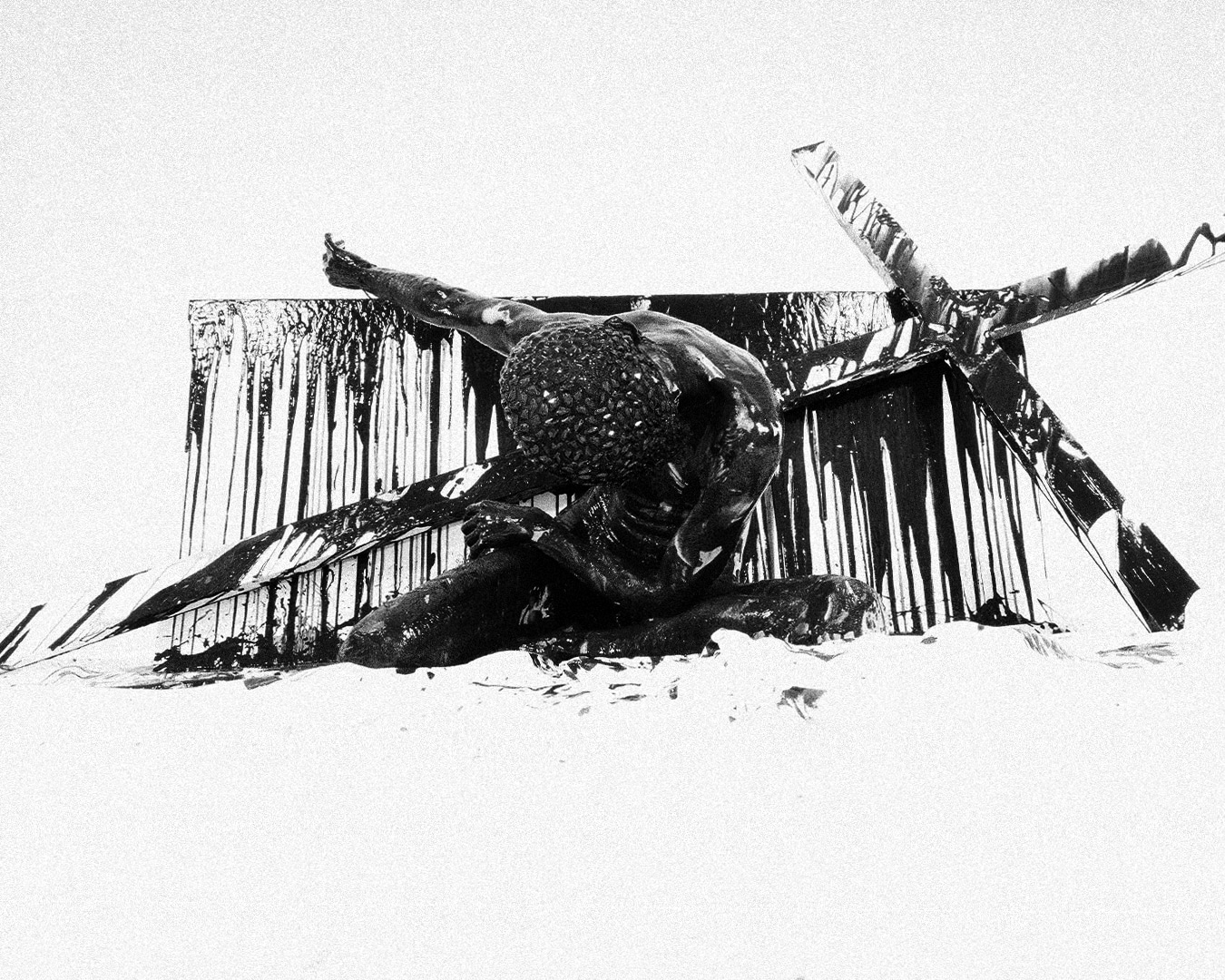

Street Fever.

Photo by Cdigi_

As Standing Rock Sioux writer and theologian Vine Deloria Jr. once said, “Religion is for people who’re afraid of going to Hell. Spirituality is for those who’ve already been there.” The quote, now a mantra of Alcoholics Anonymous, speaks to those who used to seek salvation at the bottom of a bottle. On Street Fever’s new album Absolution, a gritty and gutsy maelstrom of electronic music, the Boise-based multimedia artist shares the kind of story that could only have its beginnings in the depths of addiction’s specific hell.

Released on Street Fever’s late father’s birthday, the record is as restless as any true search for redemption. Songs like “Fate” merge spectral darkwave, Hype Machine synth-pop, and grating industrial techno; others incorporate elements of horrorcore, French touch, and phonk into shadowy and ever-shifting tracks like “Sinner,” “Trust,” and “Repent.” The persistent Biblical allusions of Absolution aren’t tied to a devotion to any organized religion, but to their past loves and tragedies: the music of Parisian duo Justice and a Bible, given to them while incarcerated in a Thai prison.

Absolution is raw and gruff, an unfiltered sonic statement that’s, at times, uncomfortably honest in its unflinching reflection of years spent struggling with substance abuse, mental health issues, and psychological terror. No two addiction stories are alike, and yet in Street Fever’s work I saw a reflection of my own lifetime exorcizing demons and smudging their remains. To coincide with Absolution’s release, Street Fever and I talked about everything from the record to uppers to hitting rock bottom, as well as the painful paths we had to take in order to find ourselves.

This feels so A.A., but tell me about your journey.

I’ve had an alcohol problem my whole life. Depression and anxiety, like my dad, so when I saw him homeless at 15, I had my first panic attack and developed agoraphobia. I was medicated for a while on Xanax when I was young, and that was one of my first introductions to something that made me feel different. And then, there’d be cough and cold pills that me and my friends would steal from stores.

Then, my mom is bipolar and goes through these episodes, where she’d be saying stuff like “there’s dead bodies in our backyard,” and I’m like, “Oh fuck. I’m like 12,” you know? So I’m visiting my mom in the mental institution, and not understanding what’s going on at a young age, but it always made me feel like that was going to happen to me. Which it did, and, now, it’s my mom visiting me in these mental institutions.

There were voices too, so with the drugs, I was just trying to cope with life and tried to survive with what I had. And, you know, but it’s all about having to do what you got to do to get through the day, you know? For me, it was uppers: cocaine, Adderall, meth — but not a ton of meth — and sometimes it’s just smoking some fucking crack, dude.

Sorry to interject, but you literally described 95% of my life, down to the bipolar dead people hallucinations. It’s kind of freaking me out.

What, really?

Deadass. The meth, institutions, voices. But you’re sober now, right?

Yeah, clean and sober for three-and-a-half years. I hit 30, and I think that’s when my life actually started. That’s also kind of the reason I’m still doing this project. It’s become a newfound purpose for me, because I love music and love making music, and always will. After everything though, it feels like there’s now a purpose behind it, just outside of “making cool music.”

Yeah, there’s always that revelatory moment. The one where you realize you’ve lost the plot, and there’s that sense of purposelessness. What was yours?

My friend had died, then I got into a physical fight with my best friend. I was just like “I’m done.”

I still keep a photo of my friend who died in my wallet. He was just always so sweet to me, and always just told me he loved me, so I just tried to tell people I love them all the time. It was that night, losing my friends. Just being fed up and done, and feeling like I hit a wall. It wasn’t even a mental institution. It wasn’t even a Thai prison. It took a fucking angel falling for me to finally get it.

Right, you spent some time in prison over in Thailand.

I went to a Thai mental institution for 45 days. They tied me up at night, I got the shit beat out of me by other inmates. It got so fucking bad, Like the fucking staff would piss in my fucking face and did whatever they wanted. It was awful. I still [came home] and did drugs to cope and got put in an institution in northern Idaho. I mean I was in a tiny fucking prison cell, handcuffed to a fucking pole for fucking two months.

I also came back with nerve damage in my wrists [from being handcuffed] and got attacked by people with AIDS. I’m lucky I didn’t get anything, while also fighting like five dudes for fucking water. So on the album, there are songs about that experience. Like this song “Trust,” is about waking up the next day in this other cell with all these people after not having water for three days. It’s weird though, because the reason why I got into making dance music was because I listened to Justice and that song “Genesis,” and they’re one of my favorite bands. So I opened it up to Genesis, and — call it the universe, or energy, or just love itself — but it helped me feel connected to something more than myself while I was just trying to survive.

I only had this Bible, [but] I wasn’t looking for answers from God. It was as simple as feeling connected to something else through a Bible and a song from my favorite band. And you, know, I felt like I did fucking die in that cell with that shit over my fucking heart. So when people ask, “Why do you use this cross in some of the visuals?,” I just tell them it’s honesty. I’d literally accepted my death with this fucking Bible over my fucking heart.

We love synchronicities!

Yeah, and my mom also gave me a cross necklace when I came home. I feel like I’m living proof that miracles are real; for me, they just came in the form of a cross. Maybe because it’s such a universal shape that I was able to recontextualize and reclaim ownership of what it meant to me in my own fucking death. But I do believe that all led me to where I’m at right now.

All these biblical references [on the album], they’re just so real for me. Like the name, Absolution, is about release and forgiveness. I fucking hurt a lot of people in my life and did some really bad things to them, physically and mentally. So I want to keep holding myself accountable, and music’s been a great reminder that. For me, a lot of it is about connection and relationships, but I was causing all these people pain with my absence — just from not being myself as a person. That was when [substances] used to have so much power over me, and now they just don’t.

Finding a way to publicly release all the shit that comes with merely existing as an addict is so cathartic, but, like you said though, the hard part is feeling safe enough to put it out into the world.

Totally, but you’ve probably had the same sort of feelings, too?

One of the hardest things I’ve ever written was about my substance abuse. But after people started messaging me like “thank you for telling my story,” or “this made me feel a little less alone,” or “this has me reevaluating my own relationship with substances,” it really made re-experiencing the pain, fear, and shame worth every tear and anxiety attack.

That’s awesome, because that’s what it’s about! At the end of the day, we have to really think about action, especially as people who can connect with thousands of others. And I know people will want to hear about fucking synthesizers and whatever here, but it’s also like, “Shut the fuck up, dude.” Because, yeah, I can share my experience through music, but [this record is] really about my story — our stories as addicts — and supporting each other.

People need to hear stuff like your story. I needed to hear your story, because at the end of the day, all addicts are family, bro.

I’ve been trying to be more careful for the same reason, too. Just so I can still do what I do, as an addict who’s also been through the mental health wringer and lost their father a year-and-a-half ago to drugs.

I’m so sorry.

Thank you. I’ve lost over 11 people now to this disease, but I’m in a unique position to speak on it – like you. So I think it’s our responsibility, as people that are in positions like we are and who’ve struggled with this shit, to say this stuff. But I also don’t like to define myself by that, because, sometimes, I just want to be the dude that makes music, you know?

It can be weird talking about it in my music. Like, I’ve gotten to points where I’ve just been super like “Fuck, dude. Do I even want to go down that route?” And then I’m just like “yeah, fuck it,” because then we can have a conversation like this, and that’s cool. But it also doesn’t completely define me. It just happens to be a big part of [Absolution], which is just honest and true. So I feel blessed to be able to share it, even though it’s sometimes like, “Why the fuck do I need to talk about it? Why does it need to be anybody’s business?”

Yeah, you’re more than just uppers and trauma.

Exactly. I’m just going to have some fun after this and just make music that doesn’t have to be this whole grandiose story. Because, sometimes, my music is written about other people’s love, or just being in a good mood, or whatever. It’ll just be something that I feel inside of myself, so I tap into whatever that is and have that really do the talking for me.

As an aside, I also wanted to say that I admire where you are on your journey, and how you’ve been able to go out and do shows. Personally, I’ve withdrawn from the whole after-hours, underground warehouse thing, partially because I know I’ll always say yes to a bump, but also because it’s been so fucking hard to lose all these people to fentanyl and shit. Survivor’s guilt, I guess.

I’m with you on the survivor’s guilt. Being sober though, I actually feel protected in those spaces, and I think it’s important for there to be some rave soldiers out there who offer some sort of guidance and are safe people to be around. To keep an eye out and know that I’m always here to help.

But it’s also important for people like us to also have fun. So I try to just go and dance, and perform, and DJ, and it’s beautiful. Sometimes though, I do go to parties and that’s when those thoughts can creep in, so you’re not alone in those things either. I’m not immune at the same time. There’s no such thing as “cured.”

*This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.