Everybody’s Album wants to scheme a Billboard No. 1. Could it work?”>

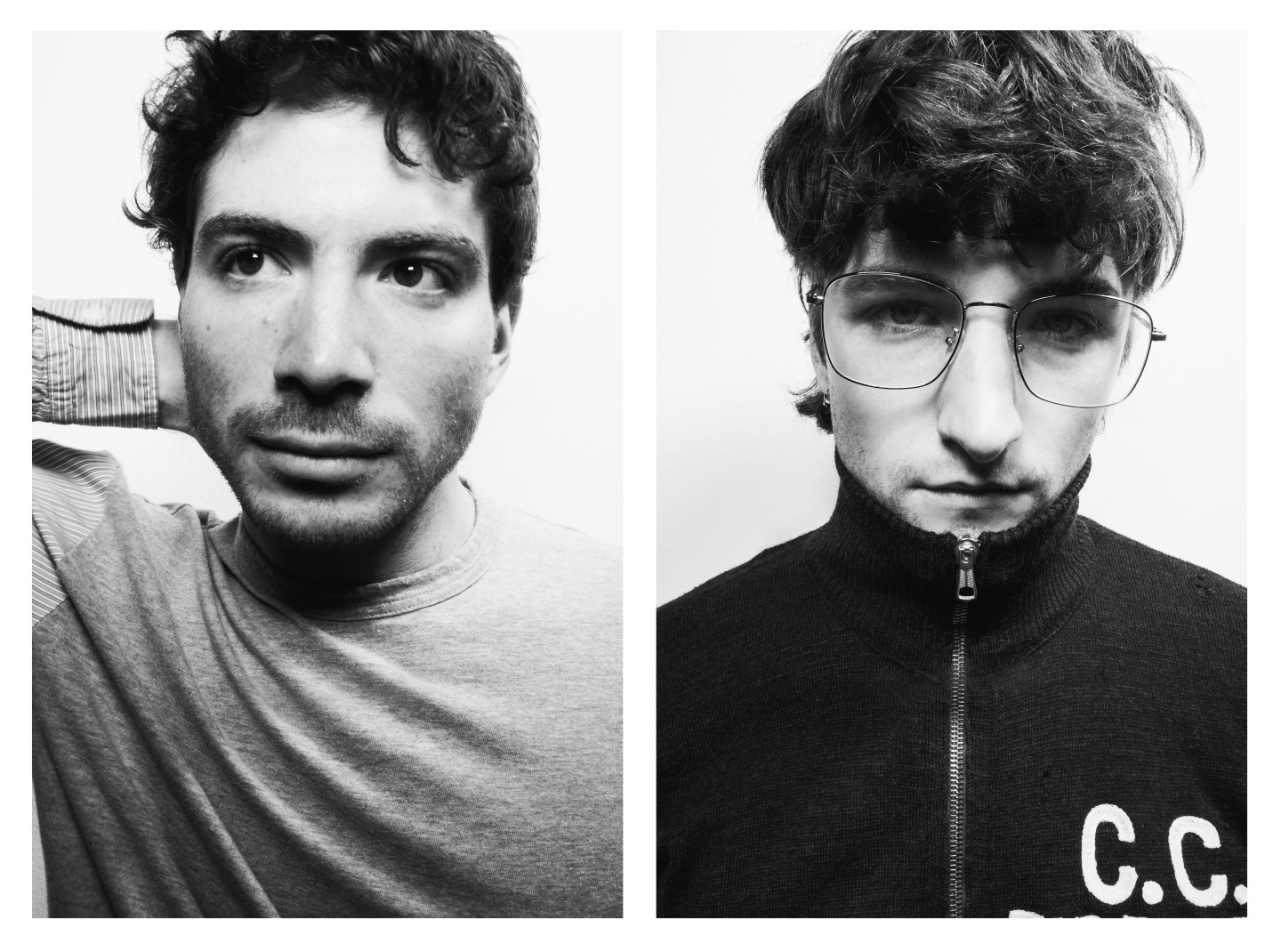

Photo by Florence Sullivan

This summer, an animated iPod Nano began popping up in my feed. At first, the iPod Nano was sharing heartfelt stories about toiling musicians and trying to use virality to give them money. The Nano’s account grew a sizable digital audience of indie music supporters, before making a sudden turn to revolution. On November 5, the Nano revealed a new grand plan: to game the Billboard charts and score a No. 1 album.

How exactly? The plan was not simple. Actually hatched up by New York City-based visual artist Danny Cole and viral creator Anthpo (the guy behind the Timothée Chalamet lookalike contest), they announced through Nano that they would pay 100,000 “everyday people” $7.99 via a digital wallet. In exchange, these collaborators would submit one second of any kind of audio to be featured on Cole and Anthpo’s new record, Everybody’s Album.

Crucially, each collaborator would then spend that $7.99 payment on purchasing a pre-order of the album. The sheer volume of these guaranteed, roughly 100,000 transactions at $7.99 each, Cole and Potero hoped, would mean Everybody’s Album would have a shot at earning a No. 1 debut on the Billboard 200.

Today, December 12, Cole and Potero released Everybody’s Album. And, impressively, Cole tells The FADER via email that their team did engage over 100,000 participants by the album’s release date (pushed back from its original target of December 5). For context, Taylor Swift’s The Life of a Showgirl, the Billboard 200’s current No. 1 (after briefly slipping to No. 3), sold 99,000 equivalent album units this week. That means if Billboard counts Everybody’s Album’s sales next week, Cole and his collaborators will have a shot to, as he says, “land on the moon.”

First, a brief interlude to talk about the actual music. To be clear, this 100,000-person album is an actual album and a genuinely charming one at that. It comprises 22 songs overseen by Cole (who functioned as quasi-A&R) and created by musicians he connected with via the community formed from Nano’s social channels. Meat computer, Daisy The Great, Marjorie -W.C. Sinclair, and other notable underground musicians that Cole declined to mention by name but says music fans will be able to spot, are among its contributors. The songs span folktronica, dense hyperpop, cloud rap, and the loose genre-assembly that’s become associated with indie artists like Chanel Beads and The Frost Children.

The choir of voices are chipper, sweet and often pitched up, evoking the cartoon world of the iPod Nano. Per the project’s intention, the last song, “Everybody” features the submitted participants’ voices all in a row, speeding up until the sound is pure noise and all 100,000 people are accounted for.

But even before all of this, a wrench was thrown into Cole’s plans. The artist tells The FADER that several days before the album’s initial release he was able to “obtain information” that indicated that Billboard would determine the album ineligible for the charts upon release. A Billboard representative confirms to The FADER independently that Everybody’s Album does not meet the company’s “eligibility criteria” for charting.

“This album doesn’t meet Billboard and Luminate’s chart eligibility criteria, which include minimum pricing requirements and safeguards designed to prevent bulk purchases deriving from a single transaction source,” the rep says. “These standards are in place to ensure that the Billboard Charts accurately reflect music consumption.”

Cole, who first thought up this idea three years ago, however, says that they “have gone to such extreme lengths to comply with every single rule” that makes up Billboard’s eligibility requirements.

In one video, Cole shows how his team went to “extreme lengths” to remain compliant. He displays Everybody’s Album‘s “Terms of Participation” which included a clause that intended to address Billboard’s rules against single-source bulk purchases. It is the “Mountain Clause,” which offers participants a cash alternative to the digital money all participants receive (and which can only be spent on an album pre-order). This alternate process required a notarized written request and a trip to a specific mountain in Nunavut, Canada, where — after a $7.98 convenience fee — the participant can receive a grand total of one cent.

After Cole and Potero obtained information about Billboard’s decision, they decided to push back the album’s release date to December 12 to suss out their next move. During my phone call with Cole on December 8, he said that if Billboard didn’t change their minds about the ruling soon, the team would have to go “nuclear.” The next day, a new iPod Nano video appeared that opened with the animation saying, “Your voice doesn’t matter … You’re just a puny insignificant bitch. This is how Billboard feels about you.” It added, “We followed every rule, but that doesn’t matter. Billboard is okay with cheating, if it’s the right people doing it.”

The “cheating” that Nano (and in extension, Cole) refers to in the video are the business strategies major artists like Travis Scott and Taylor Swift use to help them “earn” a No. 1 chart spot: releasing dozens of different merch/album bundles to boost first-week sales. Taylor Swift’s aggressive and controversial digital and physical album variants, in particular, have been accused of being a form of chart manipulation.

“[Taylor Swift] is allowed to quadruple her sales [via variants] and it’s no problem,” Cole says. “But when it’s regular people, Billboard doesn’t care if you follow the rules. They’re saying, ‘You don’t belong here.’ The charts are an advertisement that is up for sale, but you’re not allowed to buy it.” A Billboard rep did not immediately respond to a request for comment regarding Cole’s claims, but in March 2025, Billboard rolled out new chart rules to help combat these strategies used by Swift and Scott.

Despite harboring this belief about the charts, Coles also sees them as the definitive indicator of “who’s winning” in culture at the given moment. And, for once, through Everybody’s Album, he wanted to see if a more relatively unknown, indie artist could even achieve that trophy. But even so, an Everybody’s Album win would raise questions about ownership. Would the winners be the 100,000 participants Cole and Potero assembled? The actual indie musicians who traded sound files and Ableton sessions across disparate time zones? The everyday person dreaming for a chance at artistic success in a society being choked by corporate monopolies? Or, would it be Cole and Potero, who manifested this mass act of collective creation via sheer willpower and marketing savvy?

When it became clear to Cole that Billboard would not budge, he decided that all they could do was to continue to call the organization out and quietly accept that they still did something miraculous: convene 100,000 people to make a record.

One person who’s pleased with the experience is Will Morrison, a 25-year-old 7th grade science teacher from Bathurst, New Brunswick, Canada, and who releases music as Green Eyes, Witch Hands.

Morrison and his brother Nicholas sent their folktronica project to Cole, who responded enthusiastically (their music genuinely rips). Cole looped them into the project, having them add production layers and contribute to songs throughout. They created, “Jenny” which closes the record, before the recording of “everybody.”

“My brother and I were making stuff that we thought was good, but literally zero people were seeing it for a long time,” he says. “This project was like the biggest opportunity that has been given to us. Even though there was this initial plan with the Billboard thing … it’s cliché, but it’s the friends you make along the way. And we all made something really sick from this.”

In the end, it might not be a people’s revolution; just Everybody’s Album.