André 3000. Photo by Andy Feliu

“To those who in all times have sought truth and who have told it in their art or in their living, who died in honor …

To those in all times who have sought truth and who failed to tell it in their art or in their lives, and who now are dead.” – James Agee, “Dedication”

This wasn’t the Big Ears piece I expected to write, mostly because the Big Ears I went to wasn’t the Big Ears I expected to attend. As a former Knoxvillian, the weekend started to feel like some weird queer stoner version of Sweet Home Alabama, where my life is all falling into place during an emotional homecoming to the Southern town I came of age in — throughout the festival, while networking with people who know me as a writer and professional, I was also constantly having unexpected reunions with people from my past life who had not seen me in the flesh since I transitioned. Or maybe it was more like Almost Famous, considering that my mom was dropping me off to interview musicians. A Kenny Powers quote rings through my head: “I’m in a fuckin’ Cameron Crowe movie!” Unexpectedly, my life has come full circle at a festival where so many of its artists work in loops.

I went there to figure out where rap fits into the conception of the “avant-garde.” But I did not conduct the comprehensive survey of the festival’s rap acts that I intended to, since doing Big Ears “right” means following the vibrations of the present moment. If weed was legal here, every March it would be the bonafide Amsterdam of the South with all kinds of cross-branded synergistic collaborations and experiential cannabis activations wafting in the air. Besides, I quickly turned on my original thesis: if you still can’t see how rap is inherently experimental and forward-thinking and boundary-pushing, I’m not sure anything I write will ever convince you.

I didn’t see Mavi because I needed to go to the long-standing local DIY venue so people I have not seen in years could cry into my arms; soundtracking this reunion was a sweaty man hitting Les Claypool bass licks while cawing like a bird whose throat doesn’t work right. I didn’t see Roc Marciano because I ran into an artist I had been interviewing and our conversation was eager to be restarted. But rap was almost everywhere at Big Ears, even in places where you don’t think it is, if you looked and listened just a little bit closer: Herbie Hancock’s jazz-funk transmissions, Jlin’s labyrinthine footwork compositions, Los Angeles beat scene mainstays like DiBia$e and Computer Jay in the Afrofuturistic-minded Blaktronica program, the DJ in Shabaka’s band triggering lo-fi samples, even an interview I did with Claire Rousay where we talked about how Yung Lean and Drain Gang were made to be Big Ears headliners.

André 3000’s entire performance — which was more jam band than jazz band — was informed by the absence of rapping. In between extended medleys that riffed on motifs from New Blue Sun rather than recreating it as a whole, André playfully bantered with the crowd in the antique-white theater and explained how the intuitiveness of the flute recaptured the unrestrained joy freestyling did for him decades ago. The one time he broke into anything close to a bar was when he spent a full minute speaking in tongues as if a local Pentecostal snake handler had possessed him, before he cracked up and explained that it was a gibberish language he invented as a child — a perfect rib to play on a predominantly well-meaning white liberal audience who probably thought that he was sincerely channeling his ancestors.

As a former resident, when I think of Knoxville’s relationship to music, my mind drifts more to folkloric curses rather than “festy vibes.”

Ten years ago, when Big Ears returned from a hiatus of several years, a good number of these venues, as well as the surrounding restaurants and bars patronized by many of the festival’s attendees, did not exist. The Standard, which billy woods played, hosts weddings most of the year. There was basically no rap music either: in those days, you might have beatmakers like Nosaj Thing, or a more self-consciously “alternative” act like Saul Williams or Shabazz Palaces if you were lucky, but 2024 was the first year that the culture was a cornerstone of the festival. Yet when I think of my years in Knoxville, almost all of my memories are soundtracked by rap music. This is the place where I had a very short-lived career as a DIY concert promoter, until I realized that I didn’t want to spend my entire life making up excuses to people about why they haven’t gotten their money yet.

The shows hosted mostly rap acts like Milo / R.A.P. Ferreira and Serengeti, but also included a very vibes-are-off bill headlined by the short-lived twee punk group Quarterbacks, which was the subject of a write-up in this very publication that made me feel like I may or may not have been inadvertently responsible for breaking up a band I liked. I abandoned those carny ambitions and became a DJ, terrorizing disinterested and occasionally disgruntled frat bros with all the absurd Tony Hawk Pro DJ, DJ PayPal, and DJ George Costanza edits I had trawled from SoundCloud. At some point after that, I became a music journalist.

Though not necessarily considered a literary city, Knoxville is no stranger to legendary critics and people of letters: Alex Haley and Kurt Vonnegut did their time on the University of Tennessee campus, and Cormac McCarthy was made in these deceptively blood-soaked hills. McCarthy’s Suttree is celebrated by the city, even the namesake of a local restaurant, despite the fairly putrid and unpleasant atmosphere that pervades the decaying carcass of the Knoxville that he conjures: the moldy stink of dilapidated houseboats, the smell of fish slowly rotting on Market Square, the sweaty paranoia of the county jail.

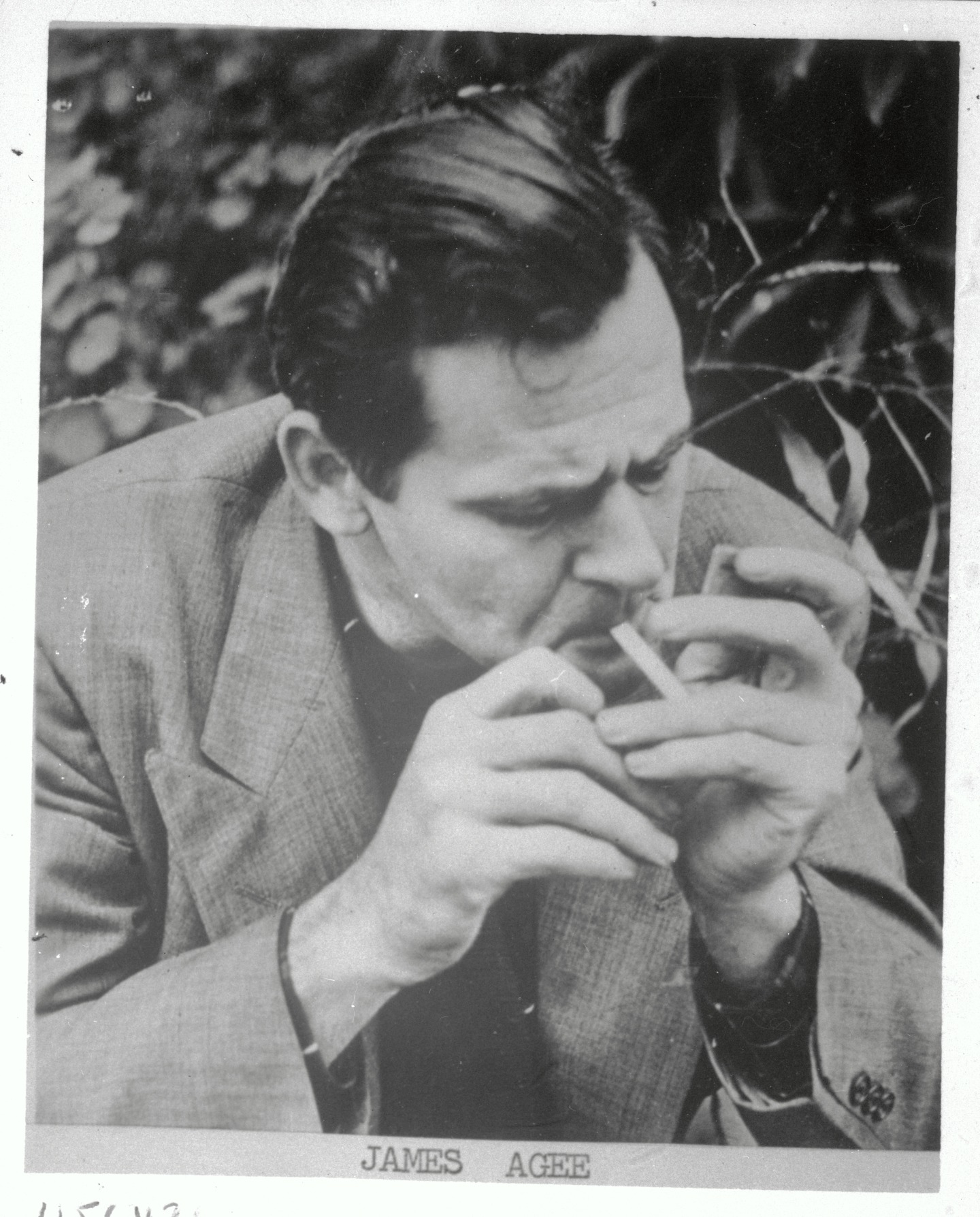

But if you told me that the vast sprawl of the city leaked out straight from James Agee’s pen and bled onto the map, I would probably believe you. My pocket-sized paperback copy of his posthumous A Death In The Family puts it in bluntly lurid terms: “James Agee was the most prodigiously talented writer of his generation, and one of the most tragic figures of our time. He had three wives and four children. He drank too much. He drove himself beyond the endurance of any human being. He was haunted by the idea of suicide and obsessed with the idea of achieving greatness.”

James Agee. Photo by Bettman/Getty Images

Artists in Knoxville — even those only passing through the city — seem uniquely plagued by similarly tragic outcomes as Agee. My friend Ben, who runs the Knoxville-based but internationally-minded boutique label Gezellig Records, has a theory he calls the “Knoxville Curse,” about the strange specter of death that seems to hang over the arts — but especially music — in Tennessee. Rachmaninoff conducted his last concert in Knoxville, and is honored with an unexpected statue in World’s Fair Park. Hank Williams spent his last mortal night on Earth downtown on Gay Street. Sparklehorse killed himself in Old North Knoxville in 2010. And several notable artists have been booked to appear at the Big Ears Festival before unexpectedly canceling and passing away soon after, including filmmakers Jonathan Demme and Tony Conrad.

Big Ears is a festival that true-blue audiophiles often see as a weekend escape to a world of healing and invigorating music, set against the immensely walkable downtown of a somewhat idyllic-seeming city. But as a former resident, when I think of Knoxville’s relationship to music, my mind drifts more to folkloric curses rather than “festy vibes.” As many novelty cocktail bars and taquerias owned by white people have taken up residence on the main thoroughfare, the constant shudder and rumble of the overpass is always omnipresent, and billboards for gun ranges tower overhead; you are never far from forgetting that the epicenter of Knoxville’s housing crisis is two blocks away from this Stars Hollow-but-make-it-Southern downtown.

My brain reverberated with memories of the Armand Hammer show where I furiously scrawled notes in the back of a New York-as-all-hell rap show in the place I used to live, feeling like nothing less than myself.

People who visit here don’t know the skeletons buried beneath these streets. They don’t know that the historic Bijou Theater, where I saw André 3000 charm his snakes, was an adult cinema in another era. They don’t know how much of the cozy downtown square was probably funded with drug money, or the fact that Sparklehorse took his life five minutes from here in an alley. We are not just in a seasonal mecca for experimental music, but the foothills of the opioid crisis, where life often seems to revolve around little more than putting alcohol into your body—from a downtown economy largely built on a liquid foundation of craft breweries and boutique distilleries, to the dive bars on the edges of the sprawl where you can still smoke indoors, to the notorious fraternity “butt-chugging” scandal that made national headlines the year before I started at UT. The rent is too damn high, and it’s only getting higher: a year or two ago, in a moment of rock-bottom brokenness, I considered moving home, only to realize that I would have been spending almost as much to live in New York without the same opportunities.

By Saturday night, I decided I needed to skip Herbie Hancock, despite his own seismic influence on hip-hop’s very foundation, and really see some fucking rap music. So I decided to fully commit to all of Armand Hammer‘s set at Jackson Terminal instead of trying to play the dangerous festival game of thinking you’ll have the energy to be in two places at once and accidentally ruining both performances for yourself because you’re invested in neither. Memphis demon music sometimes captures the vibes of Knoxville, but Memphis is its own republic. Jelly Roll and Starlito are Tennessee as all hell, but that’s some real Cashville shit forged in the shadow of Music Row, not the hinterlands of Appalachia; the slam poetry-oriented conscious rap that tends to get the most attention in an overwhelmingly white city like Knoxville has never felt right to me either. None of it reflects the constant sense of unease as you drive down roads with nary a street light save for a Waffle House in the distance, crawling up and down the interstate that slices the city in two, or the carcasses of the industries that no longer reside here.

Somehow, it was Armand Hammer that more than anything I saw that weekend captured the Knoxville I know: not the quaint place where you sometimes have to literally wait for a train to pass as you’re walking from one venue to the next, but the crumbling and over-surveilled city where great artists are always dropping dead and I still feel like I have to tuck into an alleyway to smoke a harmless little joint. As they played to an audience of r/hiphopheads who look like Kyle Mooney, in a gentrified train station where they sometimes have deathmatch wrestling next to an active railroad track, I realized that Armand Hammer are basically what would have happened if 8Ball & MJG moved to the outer boroughs instead of Houston to jumpstart their music careers. It also had the most soothingly tectonic, full-body bass I have heard at Big Ears since the 2014 festival where I fell asleep during a Tim Hecker show at 2 a.m.

Despite his prodigious talent and prolific ability, James Agee produced little in the way of conventionally-regarded “Great Works” because he had to make a living: the majority of his career was spent hustling for a paycheck as a literary critic and film reviewer. If James Agee had been born a few generations later, he may have been a freelance rap journalist. Part of why I love hip-hop is because of the kinship I feel with the grind as a perpetual freelancer — during Armand Hammer’s set, billy woods paused to quickly promote the exclusive black label vinyl they were selling at the merch table after the show, before quipping that his own impromptu sales pitch is like when “An ad interrupts your YouTube video.” Writers, publicists, managers, ambient musicians, New York rappers: this may not be a SXSW-level industry mixer disguised as a festival, but we are all here to work: I had conversations with multiple musicians about flipping equipment you have been given for free, much like I have flipped promo records in times of financial desperation.

For whatever dark energy resides here, whatever curses might have been cast a hundred years ago, there’s also something uniquely magical about the run-ins that can happen in a fairly walkable square mile. I didn’t have any kind of interview with billy woods planned, and didn’t even interview him, but we somehow spent several hours sharing cocktails, talking about everything from Quelle Chris to the Grateful Dead. The experience completely reoriented my perception of Maps: it’s a tour album, with woods in Anthony Bourdain mode luxuriating in the fact that he’s finally made it after years of unrelenting hustle, soaking up the local culture while playing hooky from soundcheck. We went our separate ways and vanished into our separate clouds of weed smoke; my brain reverberated with memories of the Armand Hammer show where I furiously scrawled notes in the back of a New York-as-all-hell rap show in the place I used to live, feeling like nothing less than myself.

Every time I return to New York, I indulge in a lucky-sock ritual of listening to Purple Haze fresh off the plane, just like I did the very first time I came to the city as a wide-eyed 23-year-old. But this time in the car back from LaGuardia, I put on Maps, specifically “NYC Tapwater,” which hits me in my bones deeper than any song I have ever heard in my life. The moment I get home, the cat purrs on my lap, I crack a fresh pound, and I still have yet to tell anyone that I’m back around.

Rap Column is a column about rap music by Vivian Medithi and Nadine Smith for The FADER.