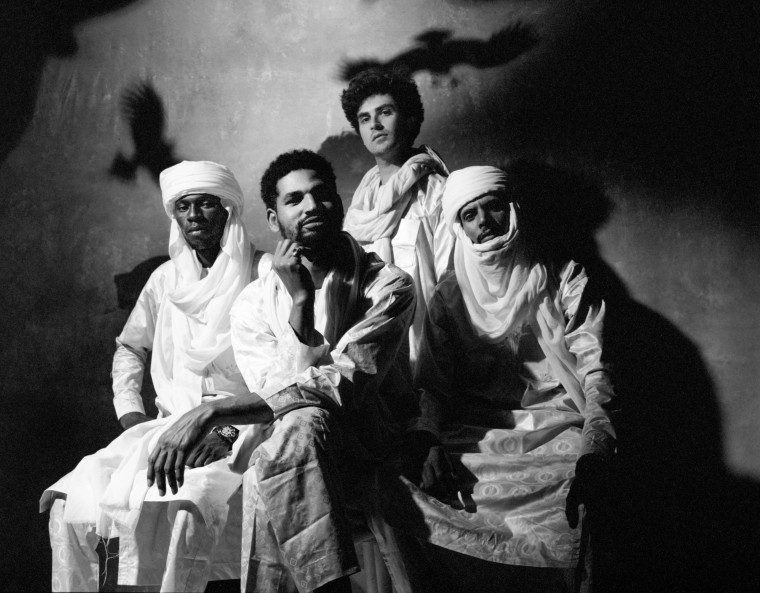

Avalanche Kaito.

Photo by Tom Lyon / Courtesy of Avalanche Kaito

The Opener is The FADER’s short-form profile series of casual conversations with exciting new artists.

From the day he was born, Kaito Winse was meant to preserve history. Like his father and grandfather before him, the Avalanche Kaito frontman is a griot, an oral storyteller, musician, singer, and historian revered by the Malinké people of West Africa as a custodian of culture. The Burkina Faso-based artist explains in an email how the roots of his role stretch back to the Mande empire in the 13th century and the immense responsibility of “safeguarding” traditions going back hundreds of years.

Winse explains that a griot’s job is “to bring society together and bring the village to life through storytelling” and conduct culturally significant ceremonies to “bring together all the children and adults in the village.” In the past, he may have served as a royal advisor to the ruler of a small Senegambia kingdom. Between multiple government coups and the rapid urbanization of the capital city of Ouagadougou, however, Winse decided to take his musicality, ancestral connections, and cultural knowledge abroad by starting a band with Le Jour Du Seigneur, a Belgian noise punk duo formed by experimental guitarist Nico Gitto and drummer/producer Benjamin Chaval.

After first meeting Gitto and Cheval in Ouagadougou’s underground music scene around 2018, Winse traveled to Europe, where the trio — dubbed Avalanche Kaito — rehearsed for five days. A short tour around the continent followed where they’d bring their bold and unexpected blend of “grrriot_punk_noise,” or what Chaval simply referred to as the trio’s “shared rhythm and energy.”

On Avalanche Kaito’s sophomore effort, Talitakum, this malleability is apparent within the first 40 seconds of “Borgo,” where Gitto’s guitar and Winse’s bowstring are barely recognizable beneath the heavy layers of feedback and distortion. It’s absolute chaos, a cacophony of ear-splitting squeals and screeches that collapse into earthy cowbells and the flutter of a Winse’s tambin flute, which makes frequent appearances amid the scarring noise.

Winse’s powerful, stream-of-consciousness statements can guide the listener through dissonance and disarray. He’s an effortlessly magnetic performer who’s able to seamlessly switch between English and several indigenous Niger-Congo languages, including Mooré, Fulani, and Samo. Every time he opens his mouth, the noisy rage becomes a sermon imbued with a power that rises above the noisy tangle of jagged polyrhythms.

On songs like “Tanvusse,” his shouts and exaltations are as forceful as the head-crushing production, pushing back against the cutting fury of abrasive, metallic noise and the head-bashing crush of Death Grips-inspired blast beats. At the same time, however, Gitto and Chaval know when to dial it down, like on relatively stripped-back songs like “Donle,” where Winse is given the space to narrate the story of his homecoming. Then there are songs like the “Viima” and the title track, where Winse adapts to the rough starts and stops of the Belgian duo’s noisy art-punk rhythms.

Regardless, every song is “very noisy and improvised,” Chaval said, adding that Avalanche Kaito is the sound of their collective intuitions. Production-wise, he does his best to preserve the “raw material that emerged from us through improvisation with as little thought as possible,” with one interesting exception.

Translated from Mooré, Talitakum means “Dead, come back to life.” Chaval alludes to this tenet, explaining how his music will utilize digital tools to help “reveal some of the hidden spirits” within the sounds. It’s a radical new interpretation of Winse’s birthright as a shepherd of Malinké culture, and one that’s helping Avalanche Kaito bring the responsibilities of the griot to the global stage.