Authentically Plastic and Gerald.

Photo by De Lovie Kwagala.

Indigenous legend says Lake Victoria is a magical place, inhabited by powerful spiritual beings. Both feared and revered in pre-colonial Uganda, these demi-gods would commune with trans and pangender shamans, who are said to embody the divine masculine and feminine energies of the lake. Even now, there are many “occultic beliefs” about Lake Victoria, according to DJ and producer Authentically Plastic, who once visited the lake with ANTI-MASS co-founder Nsasi. There, they dropped acid and heard the gods while swimming to an island in the distance.

“The waves got really intense and crazy, and I started experiencing these auditory hallucinations of a very specific drum pattern,” Authentically Plastic recalls. They place heavy emphasis on how both members of the queer Ugandan music collective barely “survived with our lives,” before realizing they’d heard “the same exact rhythm” while fighting against the chaos and confusion of the current.

They’d later reproduce the divine rhythm on their track “Galiba,” a disorienting whirlpool of pitch-black circular sound, overwhelmed by the ceaseless intensity of a “ritualistic” kadodi drum. “Galiba” is intimidating and inescapable, the militant bassline at complete odds with its disorienting rip current of dizzying GHE20G0TH1K-style loops. A deconstructed club track steeped in hurried panic and frenzied confusion, it’s fair to call it a sonic incarnation of the looming danger awaiting Authentically Plastic, Nsasi,

Turkana, and Gerald every time they stepped outside. It had to be the opening track of the collective’s 2021 debut compilation, DOXA.

Despite traditional beliefs placing queer Ugandans in high positions of spiritual power, the community currently faces the ever-present threat of harassment, physical assault, and arrests under one of the most draconian anti-LGBTQIA+ laws in the world. In May 2023, the Ugandan government enacted the Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA) as part of an ongoing string of homophobic and transphobic legislation, incarcerating any Ugandans suspected of engaging in same-sex relations or non-traditional gender expression. Similar to the 2014’s nullified “Kill the Gays” bill and 2019’s vetoed Sexual Offenses bill, the AHA mandated harsh punishments ranging from potential life imprisonment to the death penalty in cases of “aggravated homosexuality,” a loosely applied charge that Gerald dryly notes “hasn’t really been defined.”

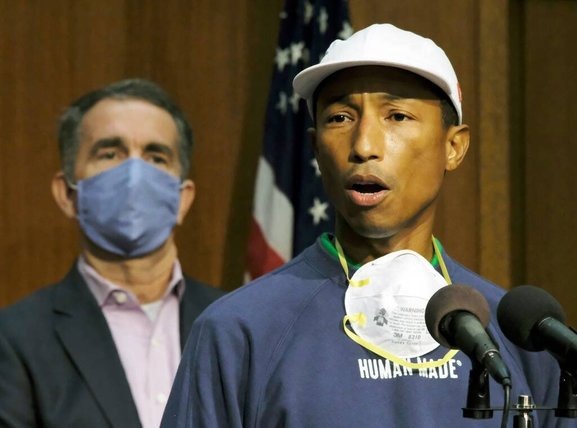

Gerald.

Photo by De Lovie Kwagala.

“It can be used on anyone… even if they just do not like the person,” they say, explaining that the law is enforced through vigilantism. Tattling can boil down to neighborhood politics, work rivalries, and interpersonal relationships, with “people being fired from their jobs and landlords still kicking people out of their homes.” It can even be weaponized for something as petty as clout, according to Nsasi, who mentions an “ex-gay” influencer named Elisha Mukisa, who allegedly sneaks into LGBTQI+ parties around the capital city of Kampala intending to out others.

But Dr. Ian Lekus of the Council for Global Equity tells The FADER that the AHA is effectively a smokescreen to hide much larger problems. It is, he says, the “work of political and religious extremists who fear free and open societies where creativity and imagination reign.”

Alluding to reports of major government and church funding by U.S. Christian evangelical groups, Dr. Lekus says that these conservative institutions are trying to distract the chronically impoverished populace from bureaucratic corruption by redirecting their anger and frustration towards ANTI-MASS and other queer artists that “defy categories, representing everything these authoritarians fear.” The ones who end up suffering from the AHA, however, aren’t just queer Ugandans, but the entire country — the law also makes “H.I.V. prevention and treatment far more difficult for all Ugandans,” Dr. Lekus says, in a country with one of the highest HIV infection rates in the world.

Nsasi.

Photo by Ian Nnyanzi.

Speaking from their new flat in London, Nsasi agrees that this anti-LGBTQIA+ zealotry is the government’s way of “distracting” the country’s majority Anglican population from the “corrupt leaders that are taking from you, and the systems are taking from you.” They list a number of issues that have fallen to the wayside in the wake of the AHA, like Uganda’s high rates of maternal mortality, chronic poverty, and human rights violations.

“You have bad roads. You have poor health care. You have poor this, poor that,” they say. “There are so many [more important] things to pay attention to than the sexual practice of one man sleeping with another man, a woman sleeping with another woman, or whatever.”

For the last decade, Kampala’s underground club scene has been considered a safe haven for members of the East and Central African LGBTQIA+ community, with many using the “artistic creativity” of nightlife to keep them safe. There were queer bars, gay clubs, Pride events, and festivals thrown by allies like Nyege Nyege Tapes, whose Ray Sapienz was the one to introduce ANTI-MASS to Ableton.

According to Gerald, the origin story of ANTI-MASS is as simple as four friends trying to create “a place for ourselves where we could host parties, play the music, and bring a crowd that we felt would gel in interesting ways.”

“There used to be a lot of parties in Kampala,” Gerald continues, though there came a point where they wanted to cultivate experimental club music from “artists doing really interesting things.” So much of what they produced was music that combined the sounds of traditional Ugandan folk and underground queer nightlife, filtered through a deconstructed club lens. And with most of their work projecting an “unpredictable,” “evasive,” and almost paranoid quality, almost every ANTI-MASS release is produced in a way that makes it easy to understand what it’s been like to exist a queer Ugandan, Turkana explains in her Whatsapp message.

Turkana.

Photo courtesy of Never Normal Records.

Like the other members of ANTI-MASS, her focus was on blending “organic and synthetic textures to create a dynamic and immersive auditory experience,” which usually resulted in an “intense and edgy sound to channel the tension and resistance.” Inspired by “historical revolutionary movements, contemporary social issues, and the vibrancy of the underground music scene,” Turkana says that focusing on more conceptual elements amid the AHA has “added layers of complexity to my work,” allowing her to “provoke deep thought and strong emotions [that reflect] the multifaceted nature of resistance and the intricate struggles we navigate.”

To some, ANTI-MASS’s sound can be intimidating and hostile. But the collective’s tendency toward abrasive noise and metallic sounds can be a way of helping people understand their experience while also allowing others with the same experience to feel heard. Lively pop-up gatherings that usually took place at houses and quirky champagne bars around the city, their parties were never meant to be solely confined to “this idea of a safe space,” Gerald says, adding that they were more excited about creating “interesting ones.”

“We were sick and tired of the status quo in the Kampala party scene and wanted to push the envelope. Rip it apart entirely around sound music, performance art, and the experience,” Gerald explains with a mischievous smile.

“A brave space,” they say, while acknowledging the power of its dual meaning. It’s similar to the way Nsasi describing their parties as “safe spaces to think,” with attendees able to express themselves in ways they’d never be able to outside, whether they’re drag queens or the hijabis who apparently told them that “‘this is the only place I feel happy to show my hair.’”

They sigh, “It was like, ‘Okay, this was very much needed.’ People can be free here.”

This freedom, they say, also extended to ANTI-MASS’s incorporation of non-musical elements into their performances. Inspired by other left-field electronic musicians, they began to branch out into other forms of expression, including live performance and visual art. But even before the AHA was made into law, Nsasi recalls the police showing up to the collective’s New Year’s Eve party in the early hours of the morning, likely at the behest of a “repressed” neighbor, they joke.

“I remember we reasoned with them that the whole world is celebrating right now. We had to play the game while not knowing what to expect,” they remember. Most times the answer used to be “give me money, give me money, give me money.” Now though, Nsasi says, it’s a lot more precarious, especially when you’re already made it onto a government watchlist.

In the wake of the AHA’s passage, Nsasi explains that it didn’t take long for ANTI-MASS to become a big surveillance target thanks to the producers’ rising international profile and the growing popularity of their parties. So like most of their peers, they fled as soon as possible, even though that meant the entire collective ended up in different parts of Europe.

“So we didn’t need to think of what could happen, because it had happened before,” they say. Their delivery is shockingly matter-of-fact.

Gerald lets out a dry chuckle, “Yes, we are queens on the run.”

This means Nsasi now lives in London, Turkana is working in Berlin, Authentically Plastic is completing a residency in Vienna, and Gerald is studying art in Munich. Their entire friend group is separated and kept apart by visa restrictions that make it almost impossible to see each other. But with no signs of the AHA going anywhere, Authentically Plastic says they’re turning their attention towards rebuilding everything from scratch and “figuring out a way to find a community now in Europe.”

While they may no longer have to keep looking over their shoulders, there’s an underlying anxiety to every ANTI-MASS track. They’re dark and propulsive productions, containing a dynamism that’s meant to be danced to, though they’ll never let you forget that this intensity is a byproduct of necessity. Between blasts of industrial techno and the incessant barrage of grenade-like beats, their caginess and heavy use of harsh glitching and spiky textures simultaneously act as a means of secretive self-protection and openly brazen protest, forced to play both offense and defense within a brutal dystopian nightmare. It’s music that’s about “encapsulating the raw energy and defiance inherent in challenging oppressive systems and the status quo,” Turkana explains, adding that the “sonic aggression serves as a cathartic outlet, mirroring the tumultuous and often confrontational nature of these struggles.”

That said, one of their biggest conflicts is also internal. Despite ANTI-MASS being fortunate to obtain European artist visas in the first place, as many other members of the LGBTQIA+ community have had to figure out alternative living arrangements, whether that be living in their cars or hiding inside a secret shelter. But the worst part is that none of them know whether their friends are safe, as “everyone kind of dispersed,” according to Authentically Plastic.

Authentically Plastic.

Photo by Ryan Molnar

“People went underground and changed their numbers, so we can’t really access them,” they say, before asking Gerald about two mutual friends. Gerald says the last they heard one was going to Zambia, while the other was still waiting to cross into a neighboring country like Kenya or Tanzania, where being queer is still criminalized, but carries a much lesser sentence.

Anywhere, however, is better than openly living in Uganda, where the government’s legitimization of anti-LGBTQIA+ rhetoric has led to an increasing number of vicious attacks, murder attempts, and other horrific hate crimes. Even presenting as anything but extremely straight can put you in danger, Nsasi says, explaining he’s been “stopped and directly questioned about my nose ring” and that even his plaited locs can be a problem, as they can be seen as “too feminine.” And as Authentically Plastic knows firsthand, the police are just as eager to stop anyone they deem a “suspect,” whether it’s to arrest or extort them.

It’s an ever-present threat, and one that’s routinely brought to their attention when “people in the community back home will reach out for help,” Nsasi says, which is hard to see when they know they can’t do anything physically or financially.

“Sometimes, it’s just [impossible] to help. It’s not like I didn’t want to, because I don’t want to be useless,” they say. There’s a hint of defeat in their voice as they say, “So I’m out here to try and be useful by showing up for my community.”

“There are all of these people in the community back home, so I wonder like, ‘Okay, did this make any sense? Is everyone okay? That comes a little as regret, but it’s a work in progress,” Nsasi says. They’ve also tried to help with emergency fundraisers and other grassroots initiatives.

“We also have our art,” Nsasi says; being “in the face of the media” can help create awareness. Even if they’re just talking about “how we feel about their identity,” attracting media attention is their way of helping their friends back home be heard. It’s as simple as talking about “being queer and in exile, but without solution,” they explain, adding that ANTI-MASS’ next opportunity to use their platform will be at Amsterdam’s Garage Festival in late July.

But that can also be exhausting, especially when they’re “depressed” and “couch surfing,” while also missing Uganda and the support systems they had there.

There’s a touch of sadness in their voice. I ask whether, despite the righteousness of bringing attention to the situation in Uganda, Nsasi or the other members of ANTI-MASS ever regret bringing attention to themselves as queer artists by doing press or continuing to throw parties. Nsasi needs to think about it for a moment.

“I do not regret my work being relevant, because that’s why we dream,” they say. “You want your work to go places. You want to be known. You want to be discovered. You want to be found.”

Nsasi seems to grow more confident as they continue to speak: “You want to be part of something special, and, of course, it’s going to attract media attention.”

“So, to be honest, no regrets,” they say. “No regrets.”