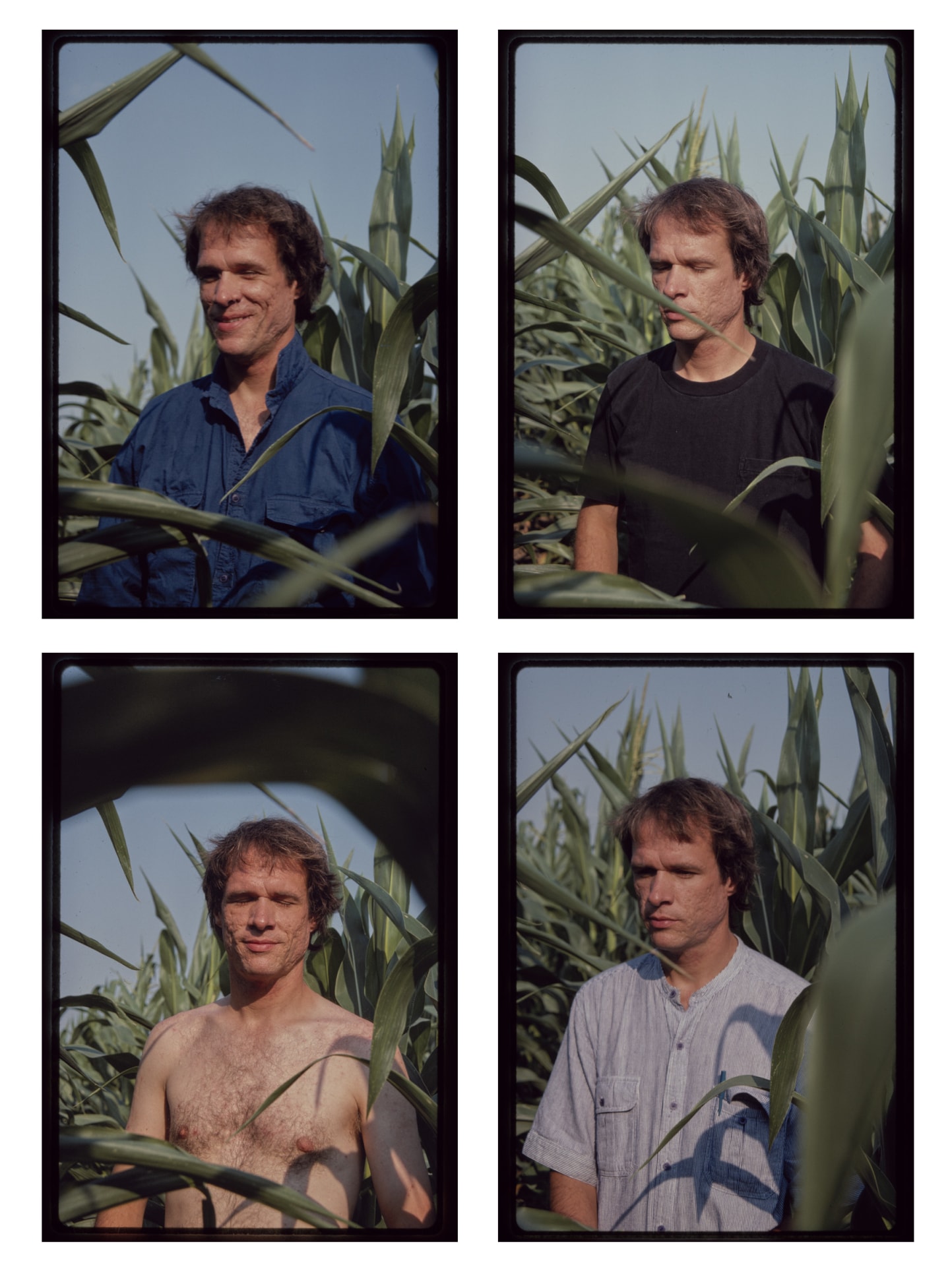

Arthur Russell during a family holiday in Minnesota, 1986. Photo by Tom Lee via Arthur Russell Estate.

Richard King remembers vividly the first time he heard Arthur Russell’s music. It was 1994, and King was in his mid-20s, working at Revolver Records in Bristol. Another Thought, the album in question, was brand new at the time, released two years after Russell died of AIDS at 40.

“I had no context in which to place this strange recording,” King writes — in reference to the album’s acoustic opener/title track — in the introduction to Travels Over Feeling, his new book on Russell’s life. “It sounded both ethereal and earthy. The voice and the tone of the cello were in perfect balance and the sense of space surrounding them felt tangible.”

Of “In the Light of the Miracle,” a an Afrobeat-influenced mid-album track that heavily features agogô bells, he writes, “[I] was struck by the realization that not only was this music I had not heard before, but it was also music I must have hoped had always existed.”

18 years later, King published his first book of nonfiction, How Soon Is Now?, documenting British rock’s transition from independent to “indie” in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. In the ensuing decade, he’d go on to write about his time at Revolver (Original Rockers), the evolution of Britain’s culture’s relationship with the natural world (The Lark Ascending), and an era of turbulence in his native Wales (Brittle With Relics: A History of Wales, 1962–97). It was Audika Records founder Steve Knutson who first floated the idea of King writing about Russell and invited him to visit the Arthur Russell Archive to see if there was a book to be made. (Audika has worked closely with Russell’s estate since 2002.)

Poring over thousands of documents from Russell’s life in the basement of the New York Public Library almost three decades after his initial experience with Another Thought, King found the purpose of Travels Over Feeling: “I didn’t try to take ownership of any kind of narrative or interpretation of Arthur’s life,” he tells me. “I wanted it to be wide open. I wanted, if such a thing is possible without coming directly from him, for him to be present in his own words.”

The resulting pages are a triumph of intermedia storytelling. They feature photographs, letters, show bills, and other archived documents from the archive, as well as quotes from his family, friends, lovers, and collaborators — including famed minimalist Philip Glass, drone master Phill Niblock, and Rough Trade founder Geoff Travis — presented as oral history alongside mostly limited, neutral prose.

Even in the book’s introduction, the only place where he inserts himself as anything more than a dutiful narrator, King gets straight to the point, summing up Russell’s birth and death in the section’s first two sentences and addressing a misguided belief about the circumstances of his later years in the following line. “Arthur Russell was born on May 21, 1951 in Oskaloosa, Iowa,” he writes. “He died in New York City on April 4, 1992, aged forty, of complications arising from AIDS. Russell’s life ended neither in obscurity nor failure.”

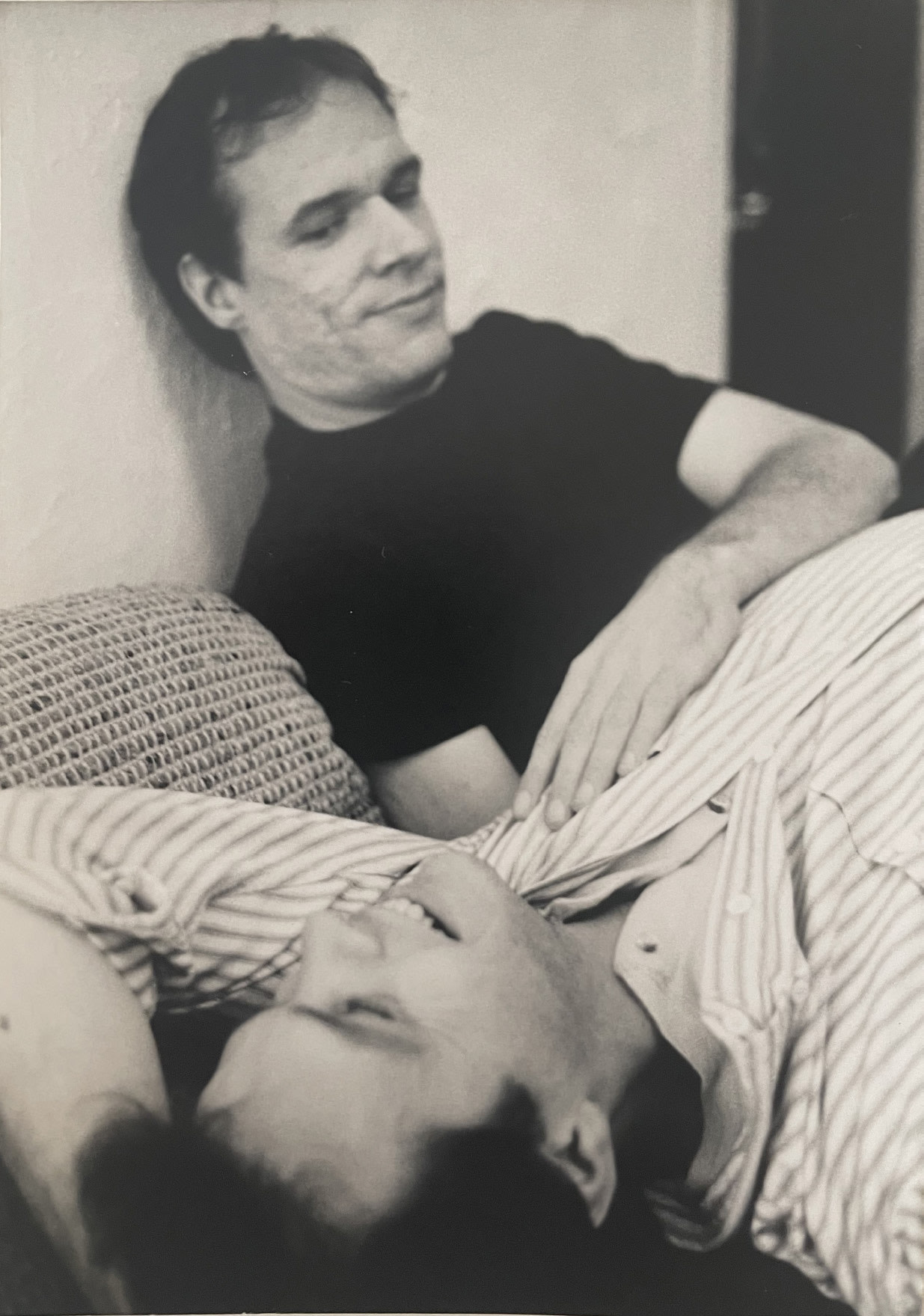

Arthur Russell (top) and his longtime partner Tom Lee. Photo by Tom Lee via Arthur Russell Estate.

On a video call a month after Travel Over Feeling’s publication, King and I discussed Russell’s messy brilliance, eschewing the titillating in pursuit of the true, and the necessary work of battling history’s tendency to flatten complex lives into neat narrative arcs.

Tell me about your first visit to the Arthur Russell Archives.

It was the week New York opened after the pandemic: Thanksgiving week, 2021. BLM had come through town, Trump had come and gone, the pandemic had come and gone, and I arrived there not having really been anywhere for the best part of 18 months.

I know it wasn’t everywhere in America, but there’s that New York thing where people just do what they need to do, and if you have to wear a mask, you wear a damn mask. Also, everywhere stank of weed, there was a huge homeless problem, and it was really cold. The combination of weed, masks, and homelessness was quite apocalyptic. I was there for six or seven days. I flew back on Thanksgiving, and there were like four of us on the plane.

Going to the NYPL at Lincoln Center in that atmosphere, sifting through the boxes and boxes of Arthur’s life, wearing a mask and everyone being distanced, the time travel required to go back through Arthur’s life was quite easy to access. And it wasn’t hard to immerse myself in East 12th Street [(where Arthur lived during his New York years)] either, because everyone’s reality was quite weird anyway. I don’t know if it made too much difference, but it was certainly exciting to get such a sense of Arthur’s life when the city was free of tourists and things were still not quite there. Opening all those boxes felt like being let in on a secret, and being in New York at that time felt like being let in on a secret.

“He was just a very complicated, strange person; he wasn’t an apostle walking among us. He was all the things we want him to be, and more, and less.”

Did you do any research outside the library — interviews, visits to the places Arthur frequented — on your trips to New York?

I went and stood outside his apartment for hours. I made four trips, and on each trip I went and just stood there. I went to East 12th Street each time and walked around the neighborhood, went to Tompkins Square Park. You don’t really have it in America, but there’s this sort of ropey thing called psychogeography in Britain where people go for long walks and think about the history of the place.

But most everyone I spoke to, I spoke to on Zoom. What was great about that was we could look at pictures from the archive together. I could say to [Russell’s collaborator and friend] Peter Gordon, “Do you remember this show?” For people who’d been asked about Arthur a zillion times, it was more interesting for them. It wasn’t just an hour of, “Tell me what you think about Arthur.” It was, “Can you please explain what this track take was in a strange club in New Jersey on a Wednesday? What was Loose Joints doing?” And then Ernie [Brooks (a former Modern Lovers member who played in many of Arthur’s bands)], or whoever sang it, would say, “It was just Arthur and a cello and it was horrible, but $500 was a lot of money.

Beyond Arthur’s sister, partner, ex, and close friends, you included quotes from only a select few of his peers who saw success outside the experimental downtown scene. How did you decide which voices were necessary to tell his story?

Arthur wasn’t especially a fan of no wave or punk. But inevitably, with history, things get elided and squashed together that don’t quite fit. [When I say I’m writing about] Arthur, quite a few people haven’t heard of him over here [in London]. And if I say, “New York, but he made disco,” people say, “Ah, Studio 54,” and I go, “No, no, not at all.”

Then I start trying to describe the loft and Paradise Garage and the Mug club, and I have to describe that he wasn’t really a scenester. Everyone knew who he was, so he was kind of on the scene, but it’s all so specifically… It’s just him, really. You can’t define him other than being Arthur.

You said in another interview — I’m paraphrasing here — that you weren’t necessarily looking to dispel the myths about Arthur, just to complicate them.

The people I spoke to [who were] close to him wanted to make sure he came across as a person, not a saint. I don’t mean he did terrible things, or that we need to make more of the fact that he would go out cruising. What I mean is that he was a very complicated, strange person; he wasn’t an apostle walking among us. He was all the things we want him to be, and more, and less.

Crucially, even having completed World of Echo, he was still trying to get people to remix his material like he had been a decade earlier. So it’s not like [he had much] career progress, and it’s also not like the early work was juvenilia or him finding his feet. The early work is extraordinary, and everything has got this quality that we all love, so I wanted to resist the idea that there’s a kind of beginning, middle, and end to his life. Obviously there isn’t, because his life was cut short tragically. What there is is this unbelievable body of work.

Tom Lee [(Russell’s life partner)] and Steve [Hall (a close collaborator)] have tried to make sense of it, and we can all try to make sense of it. But there isn’t much sense to make, other than just to think, “This is extraordinary that someone could write songs and be a virtuoso and invent a production style that hadn’t been done before.” In the book, Peter Gordon says the only person to compare [Arthur] to is Leonard Bernstein. The challenge was to get across this sense of him being everything all at once, and it being this random mess.

We can move on from the idea that he was the fifth member of Talking Heads and was at Keith Haring’s birthday party at Paradise Garage. He definitely wasn’t standing outside the Dakota the night Lennon got shot.

In your intro, you talk about Arthur’s refusal to work in one idiom or repeat himself, and that this lack of repetition was happening concurrently: It wasn’t like he reinvented himself every few years; it was all happening at once. I was struck by how effectively you were able to weave those different, concurrent parts of his life together while working chronologically. Did you ever think of ordering the book differently?

No. It was a challenge, but I kind of thought it had to be that way. [The challenge] was what to leave out as well as what to keep in, so there [would be] enough of a sense of time moving chronologically. It could just have been a kind of ad hoc, random scrapbook with the obvious [plot points]: He’s born in Iowa, moves to San Francisco, moves to New York, meets Tom, dies.

You get most of that bio stuff out of the way in the intro and in Part I, where you move relatively quickly through Arthur’s early years. Part II is when you start to focus on a really specific period when so much is going on in his life.

Yes. Once the ’80s start, he’s writing pop songs, writing an opera, releasing dancefloor music, playing new [(experimental)] music in two or three different arrangements of his friends’ bands every week, either under his name or a friend’s. It’s an unbelievable work rate, and it all culminates in World of Echo, which is released in ’86 in the U.S., ’87 in the U.K. In the time between the American and the U.K. releases, he gets his diagnosis. And then post-diagnosis, the work rate actually increases. He was really, really productive, as Geoff Travis says in the book, possibly as a way to stay alive.

I was trying to get a sense across of the industry and determination that’s there throughout. His first girlfriend Muriel says how utterly committed he was and how hard he worked, and that’s what [his frequent collaborator] Peter Zummo says about the last concert he ever played. That’s the one aspect of his character that’s not semi-occluded or indecipherable.

He was, like most people, lots of things. His sexualities, his religion… Can we say he was a practicing Buddhist all his life? Tom, who lived with him for 14 years, said it was a little intermittent. So much about him is mysterious, but the work rate and the absolute commitment and the music that produced, which many of us think is the work of a genius, are undeniable. I just didn’t want to go looking for a way of hanging all that together like a Wikipedia entry.

Arthur Russell. Photo courtesy of The Arthur Russell Papers.

Huge success or total failure is a far easier thing to understand, and total failure is far more romantic because there’s a sense of destiny.

Speaking of Muriel, her comments in Part I are the first instances where we get the idea that Arthur was not a total saint and, by most accounts, a terrible boyfriend. Were there parts of his life you felt nervous about making public?

No, but there were things I could’ve put in and didn’t. I didn’t want it to be titillating; Arthur contracted HIV/AIDS, Tom didn’t, and there’d be people who would happily give accounts of the wheres and whyfores of that, but I didn’t think it was my role to go into that stuff.

I thought avoiding any sensationalizing of his life would make it more interesting. [What’s interesting] is the everyday existence that feeds the music, that makes this concentration, this focus, this ambivalence toward success but desperate hunger for it at the same time.

His life’s pretty fascinating and extraordinary without wondering what bars he was cruising. We can move on from the idea that he was the fifth member of Talking Heads and was at Keith Haring’s birthday party at Paradise Garage; he definitely wasn’t standing outside the Dakota the night Lennon got shot.

Arthur Russell. Photo courtesy of The Arthur Russell Papers.

One myth that you do seem to be actively trying to dispel is that Arthur died in total obscurity. How do you think that came to be the dominant narrative? Cynically, it seems like a good way to sell records, but I can also imagine it happening organically, with collectors and critics wanting to feel they’d found something nobody had ever heard before them.

I think that’s right. I also think we look for the beautiful loser archetype. It’s often comforting in our own lives, when we’re struggling, to think, “Even that person didn’t have success.”

What I tried to get across was that Arthur lived a creative life for which he was frequently rewarded. He was rewarded financially, though not to the extent he wished he could have been. He was ripped off by the people who released his dance records. but he did get money out of it. Inasmuch as people could get by playing new [(experimental)] music, he got by. But he was also rewarded because he lived at a time when living a creative life was its own reward, when you didn’t have to worry as much about housing costs and food costs and all the rest of it.

It’s far more attractive to think of him as a failure, someone who died in ignominy, but he didn’t. He was a popular, highly regarded person who happened to be at least 20 years ahead of his time. It’s more difficult for us to think that that’s what life can be, that you can just get by and be so talented. Huge success or total failure is a far easier thing to understand, and total failure is far more romantic because there’s a sense of destiny. And then, with him being rediscovered, there’s a sense of destiny being fulfilled; he’s finally, rightfully ascended to the point [where] he should have been in his lifetime.

There were times when he wasn’t far off that, anyway: He nearly did an opera with Robert Wilson. He knew Seymour Stein, Geoff Travis, Karen Berg, who worked with Hüsker Du and The B-52s. In the archive there’s a memo from [legendary record producer] Jerry Wexler. People knew who he was, and it might have been something so mundane as meeting the right person, a business guy. If someone like that had managed Arthur, things could have been completely different.