Left: more eaze, photo by Tomberlin. Top: recovery girl, photo by Galen Tipton. Right: Seth Graham, photo by Zachary Severt.

When Seth Graham was 16, he started going to shows. Armed with a brand new driver’s license and some flyers from a Christian record store — the only one his parents approved of — he drove to churches and community centers to see bands from Ohio’s robust Christian hardcore scene. A decade later, he’d go on to co-found the resolutely experimental Orange Milk Records and make his own, non-Christian music with several groups and alone under several aliases.

Today, he and Mari Rubio (aka more eaze) share their second project under the unpronounceable moniker —__–___. “I like that when you look at it, you have no fucking idea what’s going on,” he tells me. For their new album, Night of Fire, they brought on post-hyperpop experimentalist Galen Tipton (aka recovery girl) to provide blood-curdling screams on each track, setting the stage for a 27-minute mine-cart ride through a pit of chaos and quietude.

The son of missionaries, Graham spent the first half of his formative years in Japan and the second half in Marshallville, a farm town best known for its tractor pulls, situated about 20 miles southwest of Akron. The church his father pastored was strictly conservative, so he was shocked to hear Christian music that sounded (at least a little) like My Bloody Valentine.

Most of the bands he saw in his late teens were nothing special, but Zao — the legendary metalcore band fronted by Dan Weyandt — blew his mind when he saw them on tour behind their fourth album, Liberate Te Ex Inferis (Liberate Yourself From Hell). “This tiny old church was so packed you couldn’t move,” he remembers. “It was almost hardcore noise, so loud and blurred and aggressive, but you could hear the intention and the orchestration pulsate through the wall of sound. It was life-changing: I was like, ‘This is music. This is exciting. I don’t give a shit if it’s Christian; it’s fucking awesome.’”

Rubio spent nearly all of her first 30-odd years in Texas — first San Antonio, then Austin — but left for New York last fall, escaping a toxic relationship, fascist politicians, and a city that had transformed during her ten-year tenure from a bastion for artists and weirdos into an ultra-gentrified tech haven. She’s brought a singular soft-noise mentality to her own massive body of work, and a raft of wildly diverse collaborations: with Wendy Eisenberg, claire rousay, Thor Harris, Pardo, Lomelda, and countless others. Her first album with Graham, 2021’s The Heart Pumps Kool-Aid, was a largely understated affair punctuated by pregnant pauses, plumes of hyperpop, and sudden stabs of stomach-wrenching horror.

Tipton — another Ohioan with a similar Christian hardcore background to Graham’s, though in a later era and with less-strict parents — featured on two tracks on Kool-Aid, but her contributions to Night of Fire sound nothing like any of her previously recorded output. Here, she returns to her screamo salad days, acting as the aggressive counterpoint to Rubio’s Auto-Tuned croons and (generally) gentle strings and Graham’s sharped, mangled song skeletons.

Night of Fire, which starts with a track called “Christian Rock” and ends with one titled “When God Released Me,” is inspired by each artist’s complex relationship with their upbringings and hometowns — fond, fucked-up memories mingling with hate for state governments that have given us some of the most brutal illustrations of the way our country eats its own.

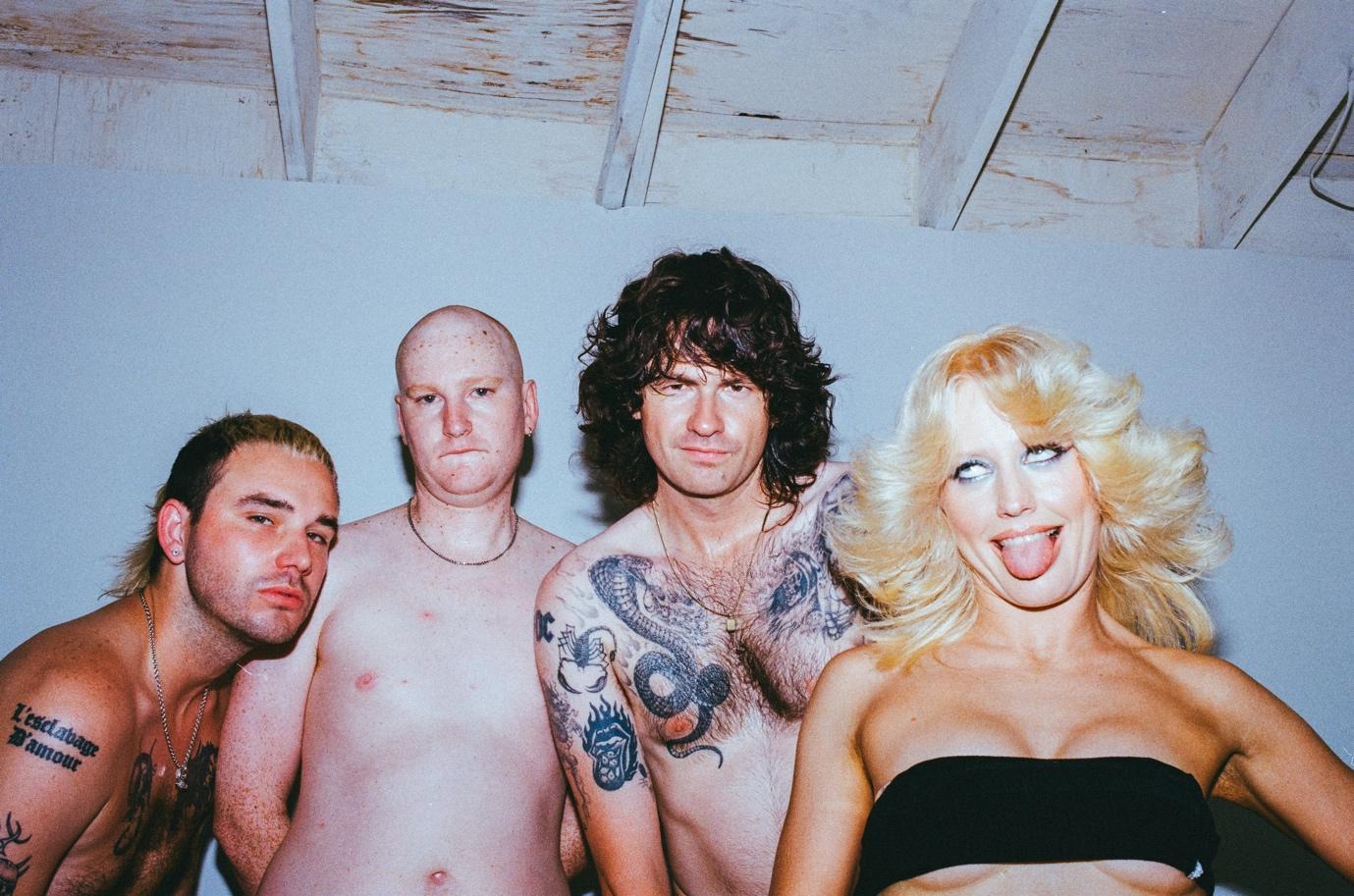

With these issues in mind, Graham, Rubio, Tipton and I sat down for a video call about the heartbreaking, algorithm-shattering mayhem of their new record.

Seth Graham. Photo by Zachary Severt.

“I’m trying to shock you out of the algorithm music you hear all day, to force you to reconsider what you’re being fed.” — Seth Graham

“Eating out on Christmas” is one of three tracks on Night of Fire whose title references religion, but its lyrics focus on relationship trouble.

Mari Rubio: It’s about knowing a breakup is about to happen while having a very expensive dinner on Christmas Eve. No one’s making the move to initiate the breakup, and the bill is going up and up as you’re prolonging this conversation. Unfortunately, it’s based on a true story.

It’s also based on memories of eating out on the holidays with my family, shortly after my parents divorced. No one wanted to have the other person over, but everyone thought the kids should be together. We’d go to some random country club — one time we went to a Shriners thing. My parents weren’t members, but they’d be like, “Let’s go here and eat this ham.” It was a bizarre thing, but I liked it in a weird way.

A lot of [my lyrics on Night of Fire] are about being in Austin toward the end of [my time there] and feeling disillusioned, living in an apartment that was like falling apart during one of the hottest summers on record. It felt especially dystopian to be in that while also being in a relationship that was destroying my life.

I couldn’t stop thinking about how these interpersonal things I was experiencing were informed by the literal, physical climate as well as the social and political climate. There’s a feeling in Texas, because of how vast it is, that there’s no escape. When you realize you can get out, it blows your mind.

“I wanted it to feel like it was made by some kid in the Midwest who kind of has no idea what they’re doing, but also by a person who’s clearly done this for some time, not a total hack.” — Seth Graham

“When God Released Me” represents everything that’s done so well on this record — the juxtaposition of these sweetly sung vocals and lush strings with walls of noise and screams. It’s got the added bonus of Lucy Liyou’s ASMR whispers as well. How did you decide to bring her in for this one?

Seth Graham: I love how Lucy does brutal ambient and spoken word. She’s so good at making things painful. When I was making that track, I asked her to laugh on it. Like, “It would be cool if you sang and then suddenly stopped and laughed.” I didn’t know why I asked that at the time, but in hindsight, I think it was because I wanted a relief, a resolve. It’s there in the title: You’re released; you’re done; you don’t have to deal with this shit anymore.

MR: I was the final person to add to that song, and it felt like a release for me, too, closing the door on the part of my life I spent in that harmful relationship in Texas. I didn’t know about the laugh, but it felt appropriate to open with a permutation of my favorite Simpsons joke: when Grandpa Simpson says, “I wore an onion on my belt, which was the style of the time.” [(The permutation: “For the record I didn’t wanna be hard / The style at the time was to be forsaken / By another / Belts tighten and loosen.”)].

“There’s a feeling in Texas, because of how vast it is, that there’s no escape. When you realize you can get out, it blows your mind.” — more eaze

“Night of Fire” is the darkest track on the record. It gets at the essence of a uniquely American violence. Starting with Galen, tell me about what went into each of your contributions to this one.

Galen Tipton: When I recorded most of these vocals in 2023, I was going through some of the hardest shit in my life. My mom got diagnosed with cancer at the beginning of 2023, and within nine months, she passed away. To be honest, I don’t even remember most of the stuff I said [on the album] after a full year of grief brain. There are a lot of different types of violence here: of the body against itself, of the medical system that made so many missteps throughout the entire process that — I’m not sure if she would’ve survived, but she would definitely have lived a lot longer.

She had an extremely rare cancer that was caused by COVID. People say the pandemic’s over, that it doesn’t exist, but I’ve seen people die. COVID is still here, and the denial — the bland, banal evil of just letting these awful things happen — is where my head has been for the past couple years. Most of what I put on this record was trying to process that in some way.

MR: The banality of evil is a huge theme for the music Seth and I make together. There’s so much anti-trans legislation in Texas right now, on top of everything else. Instead of attacking this actual health crisis and protecting the most vulnerable members of the population, we’re actively hurting another of our most vulnerable [communities]. A huge factor for me getting out of Texas was not knowing if I’d have access to my hormones the next week.

Galen’s vocals on the title track are some of the most harrowing on the entire record. Initially, Seth didn’t even know what else could be done to it, but I heard this MIDI sound that was almost emulating a really aggressive violin and was like, “I need to translate this to an acoustic instrument.” I spent a long time with each section of the song — learning the notes, but also the bow pressure, what parts of the instrument to play to get those sounds. In doing that, I think [my violin] was even more aggressive than the original, digital sound.

SG: I wanted this record to be somewhat sound designed, but also anti-sound design. I wanted A. G. Cook to hear it and be like, “This sucks.” I wanted really clean moments that go to shit. I wanted it to feel like it was made by some kid in the Midwest who kind of has no idea what they’re doing, but also a person who’s clearly done this for some time, not a total hack.

I want you to say, “What the fuck is happening?” I love Galen’s vocals with Mari’s violin because I’m trying to shock you out of the algorithm music you hear all day, to force you to reconsider what you’re being fed. But I didn’t want it to be spiteful for the sake of spite. I needed to want to hear this record.

“The bland, banal evil of just letting these awful things happen — is where my head has been for the past couple years. Most of what I put on this record was trying to process that in some way.” — recovery girl

We haven’t really discussed the tenderness each of you still seem to have for the places you’re from, which bleeds into the album most obviously on “Kill Kare.”

SG: Zach [Severt] and I filmed the video for “Kill Kare” at the Kil-kare racetrack in Xenia, Ohio. Kill-kare is amazing because you can pull up in whatever you built or souped up and say, “I wanna race.” There’s no vetting process, and there are people there watching you go as fast as you can.

If you go to other speedways, it’s a really white-supremacist vibe, but Kil-kare is really diverse in a way that’s tuned into the place I live. It’s a complicated place: a lot of blue-collar workers, a lot of poverty. But Dayton has a really diverse population because a lot of non-white people from Detroit and Chicago migrated here to take union jobs.

Anyway, we were there on fireworks night, which they call Night of Fire, and we said, “That’s the title right there.”