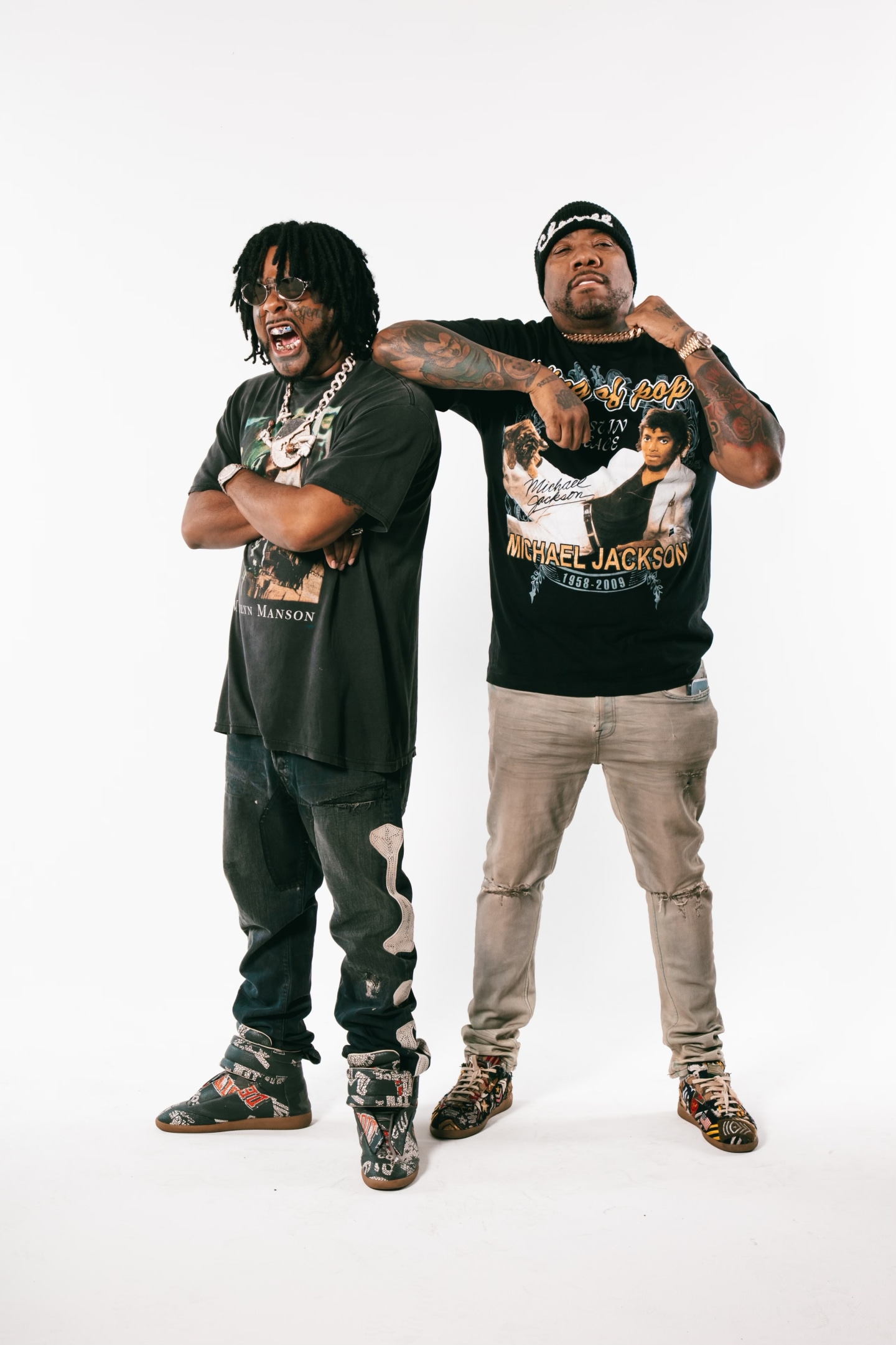

Garrett Bruce

The first time Helluva heard 03 Greedo was on a road trip. A woman he was seeing was playing his music in the car. “I’m like, ‘Damn, who is this dude?’” the Detroit producer says. She told him it was 03 Greedo, “the underground king.” “So I’m like, ‘Where he at?’ She like, ‘He locked up — and I don’t think he ever getting out.’”

It was entirely possible 03 Greedo, real name Jason Jamal Jackson, would remain behind bars until 2038. On June 27, 2018, Greedo was incarcerated in Texas to begin serving a 20-year sentence on nonviolent drug charges. The prison term fractured the Californian artist’s ascendant career trajectory even as it crystallized narratives around his hyper-vivid crime raps; legal troubles had hung over Greedo even before his December 2017 deal with Alamo Records — around the same time as his signing, he spent a few weeks in jail for missed court dates, bonding out on Christmas Day — but his April 2018 sentencing seemed akin to state-imposed career death.

From Paris to New York, Houston to Detroit, but especially in his native Los Angeles, Greedo was already a cult hero prior to his imprisonment, a myth made flesh. So his early release on January 12, 2023, felt a bit like Easter: that he served “just” four and a half years seemed like divine providence. The Californian rapper was still in a halfway house for up to 6 months, but at least he was out of prison.

But being out of prison isn’t quite the same as being free. “America’s fucked up,” Greedo says over a phone call in October while driving around Los Angeles. “You got a criminal record that’s expansive like I do, and you’re trying to bubble in this world, it’s like you got one foot in, one foot out. And you’re not trying to, it’s just fucking parole got you stuck like that.”

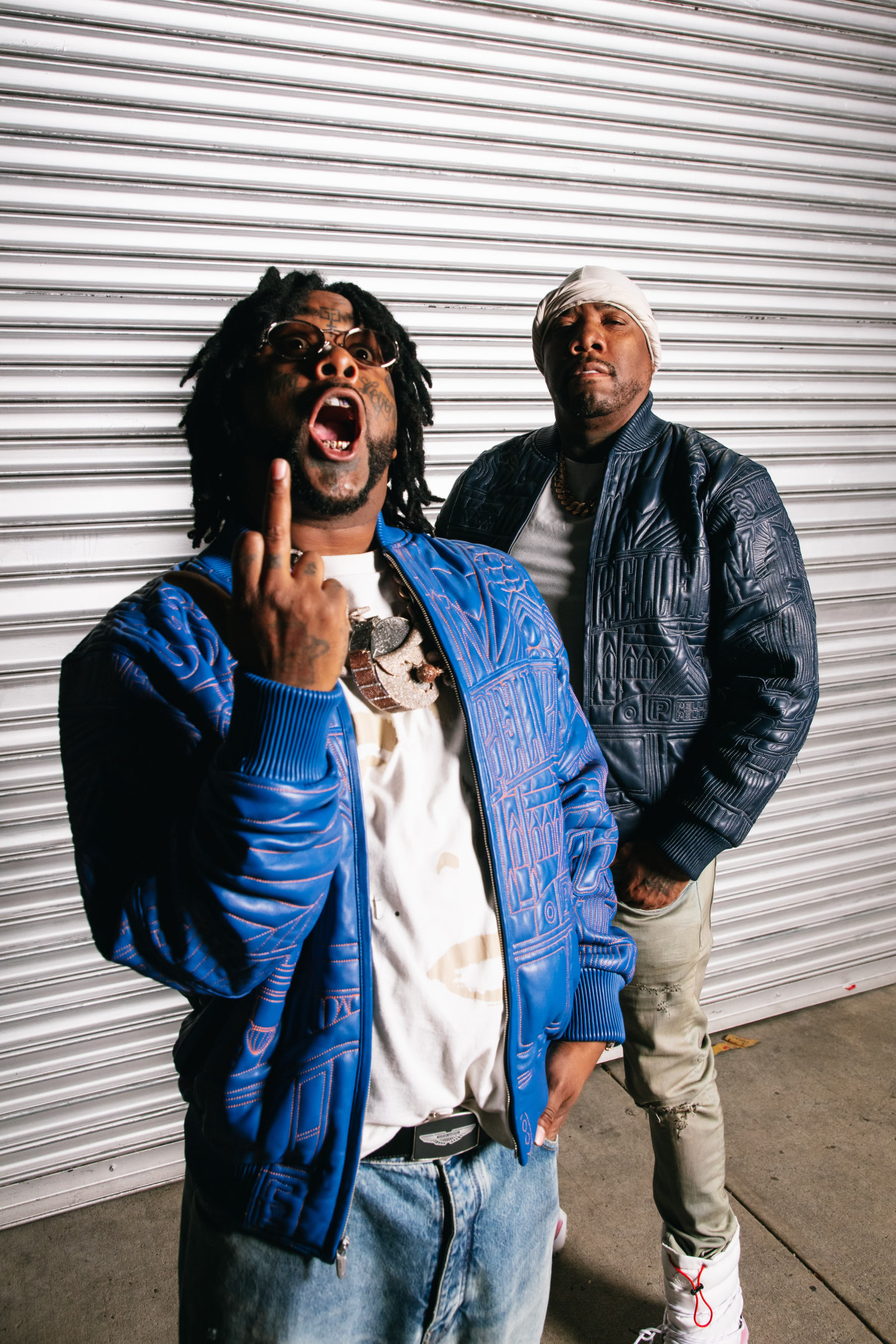

Garrett Bruce

If I had to situate 03 Greedo’s Louisiana-via-California style among more mainstream artists, I’d slot him somewhere between Young Thug and Lil Wayne. He’s the sort of lyricist who can turn a wordless melody into a titanic earworm or reel off a vicious series of syncopated bars on a whim. In conversation, Greedo is as likely to cite the influence of Phil Collins and Sting as Boosie Badazz and Lil Durk.

“Out of everybody, he don’t have no ceiling,” Helluva says of working with Greedo. “He can get on some melody shit, but he also got the vocal range to do anything anybody else could do, from Future to Uzi. And if you want to go with straight bars, he got clever punches, rhymes, syllables. Bar for bar, he would beat up on anybody.”

His technical capability as a lyricist is mirrored by his tender attention to detail and atmosphere, stitching together romance and robberies, shootouts and celebrations. To call him versatile is an understatement; at his best, Greedo dissolves outdated notions of “genre” or “regionalism,” cutting straight past conscious thought to primal feeling the same way a hook written by Ariana Grande or Paramore might.

“I’ve always said that I’m really a pop star that just happened to be from the projects,” Greedo says. “If I didn’t have to be in an environment I was in, I would never have had a gun case or been shot or anything like that. I would just strictly be talking about regular heartache.”

Zooming in on California, Greedo’s “creep music” sits adjacent to the “nervous music” of the late Drakeo the Ruler and the “traffic music” of Shoreline Mafia. Depending on who you ask, these subgenres might be arranged like siblings or Russian nesting dolls, but the general textures and tones are the same, warping the club-ready forms of ratchet and hyphy into something more imposing.

“The reason my shit is called creep music is because I know it’s all flawless,” Greedo says. “Every single piece of it is flawless, and it’s on purpose, and it’s gonna grow on you later.” He knows this is true because it’s already happened: 2018’s “Substance,” his biggest hit to date, was certified platinum in 2022 after Greedo paid for the music video out of pocket from jail.

The cover of 03 Greedo’s ‘Hella Greedy.’

Garrett Bruce

Helluva

Garrett Bruce

03 Greedo considers his latest album Hella Greedy his debut. This may confuse just about anyone familiar with the Watts, CA, rapper’s lengthy discography: Even setting aside his various 30-song-plus mixtapes (I’m partial to 2017’s Purple Summer and 2018’s God Level), he doesn’t count the more polished projects with Mustard and Kenny Beats, or last spring’s Halfway There, as official albums. “I wasn’t out to tour and do any promo for releases before,” Greedo told me back in February.

Much of Greedo’s discography was recorded under immense pressure, and so his new album, produced almost entirely by Helluva, is a product of luxury. Before, Greedo had to “put everything out, even the bloopers” in an attempt to compress years of recording into weeks and sustain his career while incarcerated. Nowadays, he can “get like 25 songs and chop them down to 16, really putting what [I] believe in the product.”

Hella Greedy is accordingly focused and fine tuned, a triumphant culmination for longtime fans that can still serve as a digestible entry point for listeners just tuning in. Recorded in Houston and Detroit, the album slaloms from shootouts to missed funerals, strip clubs to heartache. This thematic breadth is mirrored by the wide range of Greedo’s stylistic approaches: nasally falsetto’d run-on flows, diaphragm-belted vocal runs, contemplative murmurs, baritone chants, and more. Not to be outdone, Helluva’s production here is similarly wide-ranging, from the acoustic guitars driving “Militant Pt. 2” and “Devil Offa Me” to the squelching ratchet synths on “Sumn Pretty” and “Move.” The net result is a record that recalls the big-budget major label albums of yesteryear: there’s a little something for everyone and it sounds like a bajillion dollars.

Greedo’s pop instincts shine brightest on “Move” and “Move Pt. 2.” The former is a breakup anthem, 03 crooning about getting over a lover by “moving on to someone else.” By contrast, “Move Pt. 2” firmly faces forward, his delivery growing more plaintive to match the operatic intensity of Helluva’s instrumental. I walked up out that penitentiary and I had my / head to the sky, feet to the ground, pistol on my lap riding with a hunnid thou / head to skyyyyy / and I won’t budge, won’t budge, won’t budge…

“I’m just trying to move differently now,” Greedo says of “Move Pt. 2.” “So that’s why it’s at the end, it’s like a victory lap. Basically this whole album is me washing my hands of the streets.”

Still, Hella Greedy features some of Greedo’s most electric gangster raps to date, in particular Maxo Kream collab “R.I.C.O.,” a genuine contender for the best song of the year. The song’s first half is great (“How you bragging ‘bout a self-defense? You caught a free case,” Maxo tisks on the hook), and Greedo stalks through Helluva’s seething minor keys with measured menace. Then, Maxo intones as the beat twists: “We do walk ups and run downs, we on your ass can’t run now.” The instrumental’s second half, produced by Mia Jayc, sends both rappers into overdrive; attempting to dissect Greedo’s verse for standout moments would probably end with you highlighting the whole thing.

“I’ve always said that I’m really a pop star that just happened to be from the projects.”

If you had to distill Hella Greedy down to just one track, it would be “Still Feel Loaded.” Where he previously recorded with access to a cornucopia of psychoactive supplements, Greedo is now subject to regular piss tests per the terms of his parole. Sobriety and legal scrutiny, however, haven’t dampened his creative output in the slightest: I can’t do no drugs, still smoke shit / I can’t even have the pole still blow shit, goes the hook. Later, he’ll add, “Felons can’t vote so it’s fuck Joe Biden / Fuck the gun laws, all my n***as so violent.” “Me and Drakeo, we were super into the villain thing, so when that come on it just feel like a movie,” Greedo says of the song.

The album’s many beat switches are all Greedo, cutting files together in Pro Tools until concepts gelled together just so. Greedo and Helluva recorded most of the album in person, working on beats and verses concurrently in adjacent rooms; Greedo’s verses are freestyled and unedited, though he would go back in to tweak aspects of the production. He characterizes the longer development process as both rewarding and “a bit nerve wracking.”

“I feel like I gotta put them extra bells and whistles because I don’t like when people be saying, ‘Oh, no one’s going to hear Cali music past California.’” Greedo says. “So that’s why I came home really trying to go extra hard.”

If Hella Greedy is truly his “last street album,” it’s hard to imagine a better way to close out this chapter of his career. When I ask about balancing tougher songs with the album’s more romantic middle suite, Greedo shrugs off the notion that the two would be separate at all.

“The streets are very romantic. There’s a lot of love and heartbreak in the streets. You lose a lot more people that are close to you in the streets than in the regular world,” Greedo says. “My whole image has been trying to show people that the people from the projects or from the streets are not monsters, but we go through human situations, just as much if not more than people in the square areas. You feel me?”

“Sometimes you might have a thug killing his n***a, and [he] might be a hopeless romantic,” Helluva chimes in. “A hopeless romantic, tenderdick motherfucker.”

“Exactly,” Greedo says. “Future has the most love songs and more platinum hits than Beyoncé, and he’s the street-est artist ever. I had to master saying some of the foulest shit and making it sound beautiful. Because in my project, that’s what they do with conversation, so I try to translate that with my music.”

“The streets are very romantic. There’s a lot of love and heartbreak in the streets. You lose a lot more people that are close to you in the streets than in the regular world.”

Don’t get it twisted: 03 Greedo is still 03 Greedo. But he wouldn’t mind if haters doubting his credentials wrote him out of gangster rap entirely. “People don’t understand that after doing five years in prison for kilos, you want to show people that you could be on Tostitos commercials like Snoop [Dogg] and ‘em,” Greedo laughs. “You definitely want to clean your whole story up. Go ahead! Delete me out of the street world so they just accept me as the squarest trademarking ass artist they can find.”

He’d like to get off parole, fly out of the country and see the world; hide away somewhere to work on art and fashion. He wants to “start painting with my brother Nyree,” a visual artist working on Playboi Carti’s I Am Music rollout. He says his next album, The Life I Deserve, will show more of his pop influences, closer to his feature on Mach-Hommy’s Kaytranada-produced “RICHAXXHAITIAN.” Maybe after he’s fulfilled the terms of his deal with Alamo, he’ll return to self-producing his music, though he’s in no rush.

Going forward, 03 Greedo doesn’t “want to make music that makes people want to do anything but happy shit,” he says. “Being from such a demonic environment in the past, I don’t want to be on that. Nobody gets all their friends killed to want to get their new friends killed. No one gets shot at and make it home to try to get shot at again.”

“At the end of the day, I’m on the phone with The FADER magazine in an Aston Martin,” he adds. “You can’t trick me into thinking this isn’t a miracle and I just had a life sentence last year. I’m exactly what I wanted to be when I was 12. You’re not confusing me.”