@mishaspice

This story is part of our fall 2025 series, Offline, where we investigate IRL spaces and explore our relationships with music and the internet.

After hopping a turnstile on his way to a Manhattan gig in 1998, punk-turned-jazz drummer Ryan Sawyer was approached by a pretty young woman in a miniskirt and halter top. “She and her partner were these weird 21 Jump Street undercover cops,” he says. In his haste to make it to the show on time, he’d left his wallet at home, and the officers told him they’d have to bring him in if he couldn’t provide proof of his identity.

“I was dumbly searching through my cymbal bag, as if my ID would be in there for some reason, hoping they’d get distracted or lose interest,” Sawyer says. “Then, in the bottom of the bag, I found a flyer I’d made for a show I’d done. It was pretty abstract with all this typewriter art on it, but I had put the instruments next to everyone’s names because it was jazz. So I pulled it out and said, ‘Look! Ryan Sawyer — drums! Look! These are my cymbals! These are what drummers have!’ They were like, ‘Yeah, all right, dude. Just get away from us.’ The flyer saved my ass.”

Coming up in the San Antonio/Austin DIY punk scene in the early ’90s, Sawyer saw flyers everywhere. Following in the footsteps of local punk heroes like the Big Boys, the Dicks, Scratch Acid, and Fearless Iranians from Hell, he and his friends would print their flyers at Kinkos — where everyone always knew someone on the graveyard shift who’d hook them up with free 8.5” X 11” paper — and tape them up at every bar, club, coffee shop, record store, and telephone pole in town. “Flyers were the deal,” he says. “Everyone did it.”

Sawyer stopped flyering in the mid 2000s; early social media sites provided an easier alternative, and he was going out on tour a lot. But the next generation was still at it. “When I was growing up, I learned about a lot of shows via MySpace bulletins, LiveJournal communities, and friends, but getting handed flyers while waiting in line for shows or leaving shows was also big,” says New York DIY lifer and author Liz Pelly. “When I started getting more seriously involved in booking in the early 2010s, the main way to promote shows was Facebook event pages, which always felt like such a chore. Making flyers and bringing them to shows and local coffee shops and venues felt more fun and real.”

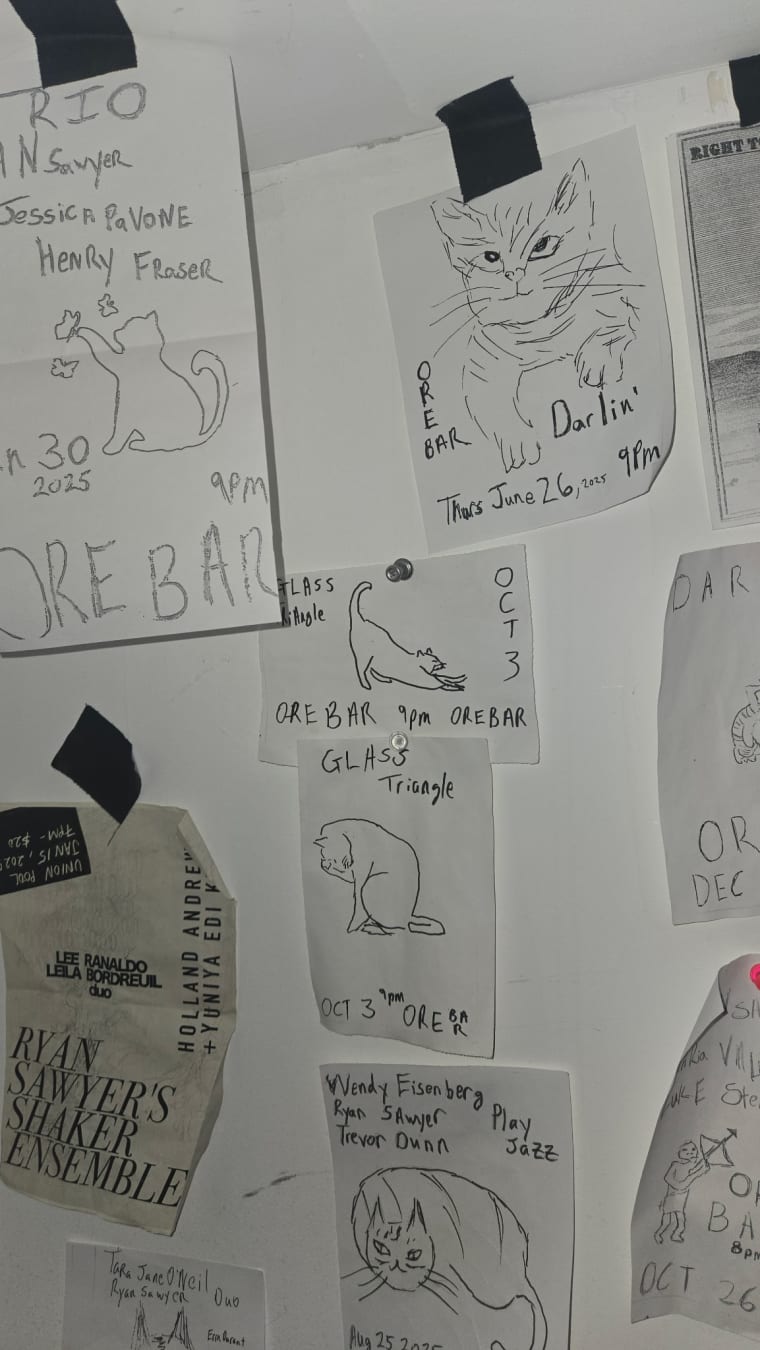

Homemade flyers by N.Y.C.-based musician and drummer Ryan Sawyer.

Photos courtesy of Ryan Sawyer

Photos courtesy of Ryan Sawyer

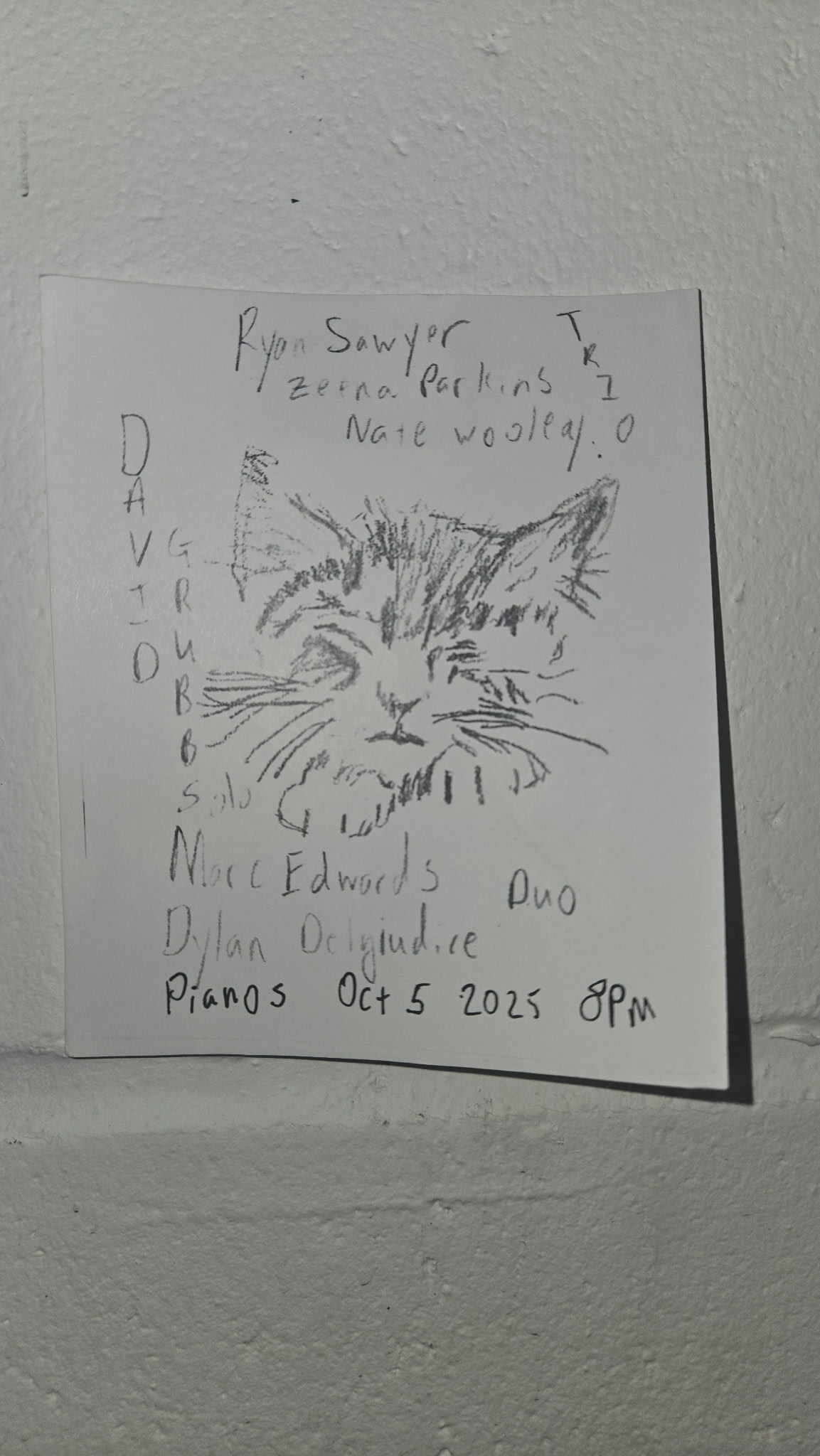

Homemade flyer by N.Y.C.-based musician and drummer Ryan Sawyer.

Photo courtesy of Ryan Sawyer.

Things are different today. Sure, bands still tack flyers to the bulletin boards of local cafés and slap stickers on the bathroom walls of your favorite dives. More and more, though, these are simply dressed-up QR codes designed to get you to an artist’s streaming and social media pages. The promise of global reach and the allure of algorithmically targeted audiences make social media marketing difficult to resist.

Time is the top concern for most independent musicians I talk to about the prospect of promoting themselves offline. English electronic artist Loraine James says she’d like to make more physical media, but that “in this day and age, it’s more or less impossible.” And “rough kuduro” originator Nazar, who envisioned a full magazine to extend the universe of his debut album, had to table it for the time being. “Someday I would love to have the physicality of print,” he says. “It’s still loading up for the future when the conditions are right.” As earning a livable income through art feels more and more like a pipe dream for all but a select few, many musicians wonder if promoting themselves in the real world is worth the effort.

“Flyers were the deal. Everyone did it.” —Ryan Sawyer

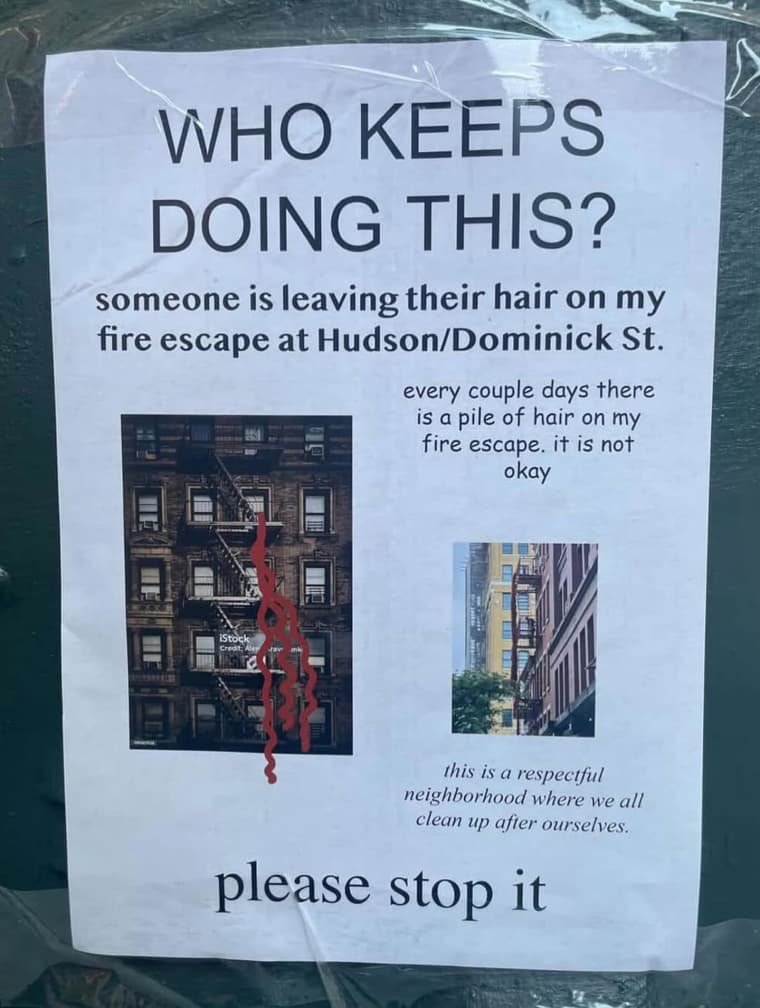

Bright red hair carpeted the streets of New York City this summer. First, flyers announcing a lost wig appeared on seemingly random streetlight poles. Next, said wig was seen hanging from a fire escape on the corner of Hudson and Dominick Sts. in Lower Manhattan. Then a new flyer was found taped to a fire alarm box on the same corner, allegedly posted by a disgruntled tenant of the apartment where the hair was hung. Days later, the wig was found wandering the city’s subway system on human feet.

This string of pranks culminated in the release of Chappell Roan’s latest single, “The Subway,” on August 1. The mastermind was Roan’s creative director, Ramisha Sattar, whose love of physical media has led her to push her projects offline. “We had my stationery box, my craft kit, and so much hair and glitter,” she says. “We stripped back the marketing because we didn’t want it to be so obvious that it was put out by us. It was a fun design challenge; we were using fonts like Comic Sans because we wanted it to look really scrappy, like anything else you’d see on a telephone pole.”

@mishaspice

@mishaspice

This type of unconventional advertising — aimed at catching passersby off guard and eliciting an emotional reaction that will sear a brand into a potential customer’s memory — is commonly called “guerrilla marketing.” Some big-budget examples: the red balloons tied to sewer grates in Sydney, Australia to promote the 2017 film adaptation of Stephen King’s It; Frontline Flea & Tick Spray’s giant dog decal on the floor of a Jakarta, Indonesia mall, creating the illusion to upper-floor observers that the people walking at ground level were canine pests; TNT’s “Push to add drama” button, which triggered (fake) ambulance crashes and gun fights in the town square of a small Flemish burg; and, of course, Imogene Strauss’ blanketing of the world’s major metropolises with coats of “brat green” paint.

Sattar’s ingenious wig-work may have been accomplished cheaply, but it was part of a much larger promo push, with artful images of Roan mounted and wheatpasted on strategically scouted surfaces in New York and beyond. Needless to say, very few independent artists have the budget for a creative director at all, much less one of Sattar or Strauss’s stature.

“Guerrilla marketing” is one of those late-capitalist phrases that deftly twists a word synonymous with revolutionary politics into adspeak, and most DIY artists probably wouldn’t admit to engaging in it. But even the most militantly punk and experimental acts to achieve a modicum of monetary success have done so, in part, through branding. Sawyer remembers seeing the teeth from Swans’ Filth cover and Einstürzende Neubauten’s stick-figure symbol, for instance, as vividly as he does the logos of the post-fame Sex Pistols and Ramones back in his San Antonio days. If one plans to survive as a musician without a separate full-time job, generational wealth, or a billionaire benefactor, one must ask oneself: Would Black Flag be the household name it is today without its famous four-bar banner?

Sawyer started flyering again when the COVID pandemic began to subside. “I wanted to get away from the phone,” he says. “There was so much doomscrolling, and I felt like it was brainwashing me and seeping in through the edges of it all.” Back in the day, he worked with painstaking precision, writing with stencils and copying graphics from architecture and magic books. Now, as a full-time musician playing roughly 15 shows a month, he doesn’t have the luxury of time, so he pumps his flyers out in bulk — marked with minimalist drawings of cute cats and fast-scribbled but cleanly presented information.

His distribution approach has changed too. Rather than affix his flyers to inanimate objects, he hands them out at shows. Between the shows he plays, the shows he attends for pleasure, and the shows he works as the manager of Union Pool’s DJ program, there’s rarely a time when he doesn’t have a flyer in his hand.

Sattar, too, has tips for affordable physical promo ideas that go beyond run-of-the-mill flyering, though these take more time than Sawyer’s quick-draw designs. She suggests using templates from online archives as guides to create custom zines and risograph printing to make the graphics pop off of the page. For the pop stars Sattar works with, an effective flyer is one that subverts notions of the depicted artist. “It’s something that makes you do a double take,” she says. “Maybe it doesn’t stand out visually as crazy, but then you look back, and you’re like, ‘Wait, is this for that artist?!’”

Sawyer’s flyering strategy within New York City is designed to build a fraction of the awareness for DIY acts that a star like Chappell Roan enjoys worldwide. “I’m going for an aggregate resonance that’s twofold,” he says. “One is that the flyers are identifiably crude and/or gestural, so they become the branding, and it’s iconic. It’s hard to deny that my handwriting is terrible and my cats are crudely drawn, so when you see that, you’re like, ‘Oh, that’s a Ryan show!’” I can attest to this resonance; I knew Sawyer by flyer long before we met in earnest.

“It’s something that makes you do a double take. Maybe it doesn’t stand out visually as crazy, but then you look back, and you’re like, ‘Wait, is this for that artist?!’” —Ramisha Sattar

“The other resonance,” he continues, “is that you then take a picture of the flyer and put it on social media, and people are reminded of the flyer they have in their pocket because of the algorithm, however wayward it is.”

Social media promises to help artists find their audiences, just as it allows companies to aim their ads at their most likely new customers by selling our personal data. The odds of an offline ad reaching someone who’ll respond to it are far less predictable, but physical promotion offers a democratic advantage.

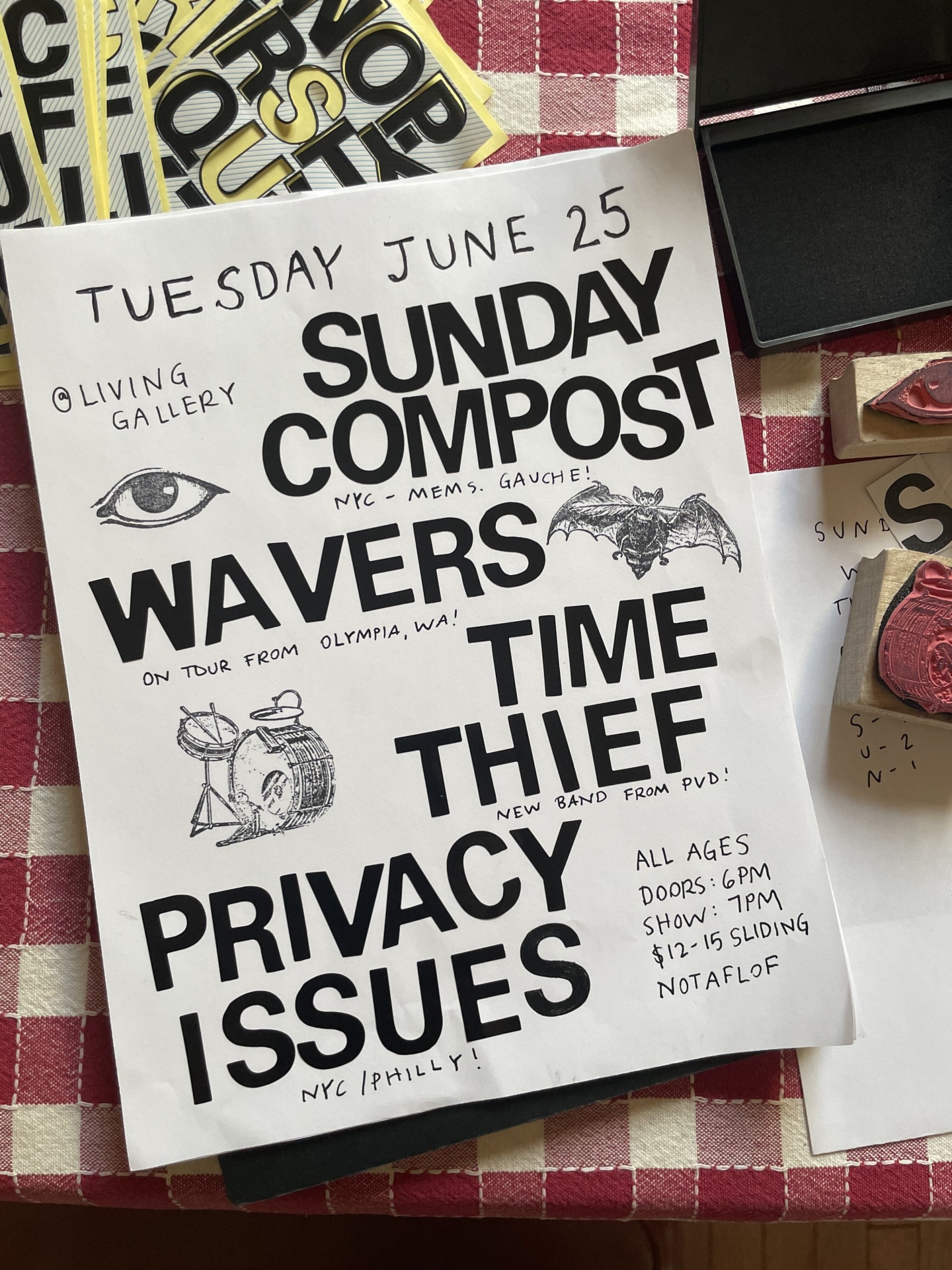

“As the platform era played out and everything became more algorithmic, hyper-personalized, and insidious, flyering started feeling more crucial,” says Pelly, whose new book Mood Machine is a headlong dive into the hellhole of Spotify algorithms and whose current band is called Privacy Issues. “There’s so much to be said about the value of having a flyer hanging in a public space. It gets out of filter bubbles and can reach people who reject or avoid Facebook and Instagram for matters of principle.”

A flyer for Liz Pelly’s band Privacy Issues.

Liz Pelly

“Having a flyer route is almost as meaningful as the show itself.” —Liz Pelly

Beyond its strength as a marketing tool, flyering is a good way to check in with people you don’t see often enough in the course of daily life. “I haven’t booked a lot of shows in the last few years, but whenever I do, the process of making a flyer and having a ‘flyer route’ is almost as meaningful as the show itself,” Pelly says. “Having a list of spots to leave flyers is a nice way of saying hi to friends and staying connected with what’s going on locally.”

Most importantly, a flyer is a physical document of an experience, assuming you make it out to the show in question. “After it’s over, it’s not like you go back to your Instagram [and look at the post], but you do find the flyer somewhere, and you’re like, ‘That was so cool!’ or ‘What was the name of that band?’ or ‘That’s when I met so-and-so,’” Sawyer says. “It’s a signpost that’s helpful and romantic. It has its own gravity.”