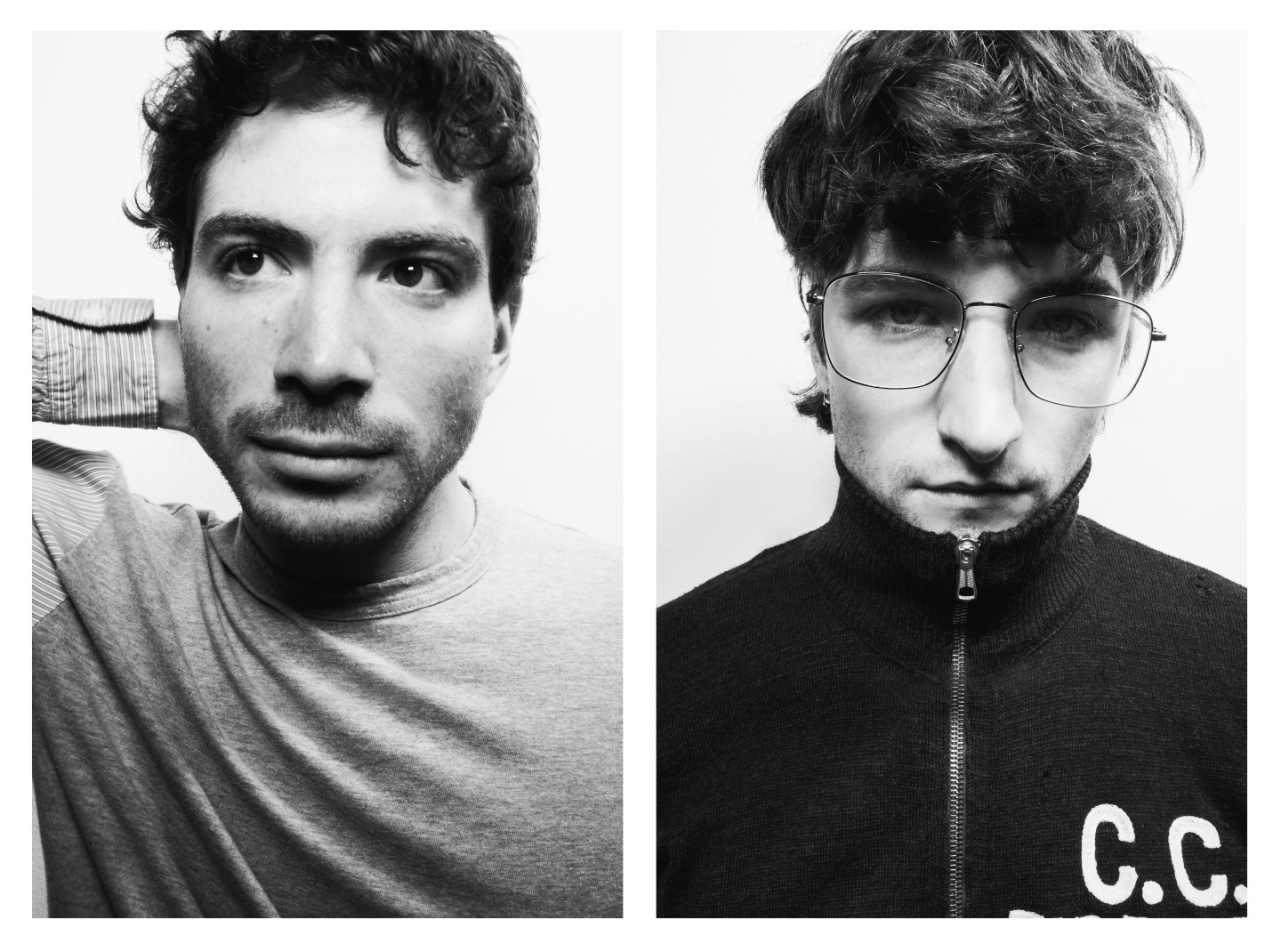

Dua Saleh

Grant Spanier

When Dua Saleh jokes that the second moon is fucking everything up, it’s really just code for mankind. We’re on the precipice of a presidential election, still reeling from a pair of Category 5 hurricanes and bracing ourselves for an incoming severe solar storm.

“The flooding happening throughout the U.S., the fires on the West Coast,” the Sudanese American artist says, adding to the list. There is also “the piles and piles of trash and technological excess and waste” a few miles away from their extended family, who are living through what’s at least the country’s third civil war in 20 years.

It’s almost enough to compete with the environmental apocalypse depicted on their full-length debut, I SHOULD CALL THEM, where a tumultuous past relationship serves as “an allegory for human interactions with Earth.”

“It’s about how we fell in love with Earth when we were first born into the world, as organisms and as humans,” says Saleh, who also starred as Cal Bowman in Netflix’s Sex Education. “But there’s a bit of toxicity and back and forth between us and the Earth,” they continue, while detailing the personal reckoning that came with writing their most forthright work to date.

I SHOULD CALL THEM is a beautifully conflicted and layered work that still feels intimate, while also addressing so many global and domestic sociopolitical issues. They write about queer love, situationships, and anxiety in a way that’s painful and direct, held up against a chaotic backdrop of experimental pop-R&B that incorporates elements of heavy metal, trap, hyperpop, and Sudanese orchestral music. The album’s woozy textures and cinematic crescendos were created alongside close collaborators Ambré, Gallant, serpentwithfeet, and Sid Sriram. Saleh’s doomed love story is a tale of both agony and ecstasy, brutal in its simplicity and told so beautifully, there are points where it truly feels like the end is nigh.

The FADER: Why decide on a narrative-driven record?

Dua Saleh: I write songs in a way that’s flowery because of my poetry background. Distraction has been a way for me to avoid vulnerability but I didn’t want to cloak my words in this rich complexity, I wanted it to be raw and pungent.

It actually brought me back to the era when I was doing open mics. There was one in particular that was a few blocks from my mom’s house, where the poets who’d come on stage spoke in these accessible ways. I’d start crying hearing their words, more than when I was listening to somebody else using theatrics for a “slam poetry” style performance.

Writing [I SHOULD CALL THEM] also reminded me of my historically Black neighborhood. There are ways to be an orator outside of white academia, which is enriching for the acquisition of vocabulary, but not always reflective of real life experience.

I feel like that’s what this is, though, so I’m excited to put it out because I’m making my neighborhood proud. In my heart, I feel like the neighborhood that I was primarily raised in, the people will hear the music and finally hear me. [I SHOULD I CALL THEM] is processing my love life, and I wanted to give people insight into my lived experience by making the songwriting more accessible. The conceptual and heavy stuff is still there — in the overall story and sonically in the production — but I wanted people to understand the lyrics.

Speaking of the production, the album is much more experimental musically than your past releases. What was the impetus for this?

As a story, it’s all about two lovers that fall in love, move away from each other for a bit because of toxicity, find each other again, and then reach the apex of their relationship — just as the world is falling apart around them. The climax is “2excited,” which starts as contemporary R&B with some jazz fusion and, at the end, you hear me screaming with the guitar and a double kick-drum before exploding into a black metal song.

It’s part of a concept I begged the executive producers to put onto the album, because I wanted to do a screamo R&B song. But they thought black metal R&B made more sense, because screamo is a bit more angsty and requires certain inflections. We did attempt it, but I didn’t realize how complex doing screamo would be. Technically though, I think we did create a new sub-genre around this song: Black R&B.

Since this record is deeply rooted in your own personal experience, did you consciously try to incorporate any sounds or imagery in homage to your identity as a queer, Muslim, first-generation Sudanese American?

I wanted to do an R&B project, because it reminds me of the Rondo neighborhood where I grew up in Minnesota. The Black musical sound of R&B also reminds me of traditional Sudanese music. It brings me back to a place of listening to operatic Sudanese singers using the pentatonic scales that Destiny’s Child and Beyoncé were also using to be expressive in their singing.

I’m influenced a lot by the orchestral sound of Sudan, a lot of which came between the ‘80s and blew up in the ‘90s. I also do like the traditional sound of oud-playing, which sounds like guitar-playing in the U.S. So in “time & time again” featuring Sid Sriram, we added guitar just to make it seem more natural and bring it back into that ethereal string sound.

Was there a reason you didn’t include an actual oud?

Just access to players. They’re really difficult to find, and I wanted to have a Sudanese person do it. But that’s probably going to come in a future project that’s more organic-sounding and more influenced by actual musicians from Sudan.

That reminds me, in Sudan, there are a lot more women who are musicians, because we’re such a musical landscape. Like my aunties will play drums at town gatherings and stuff, where everybody will sing along, and some of my other aunties play strings and stuff like that. They know how to play viola and violin, and you’ll see them in the orchestras now, mainly because of modernization. There’s more access and less of an effect from what some might call it “Middle Eastern imperialism” and [conservative Islamic tradition], I think. I can’t speak for everybody, but I think it’s cool that Sudanese women do that, and how people will bust out into songs at everything.

My siblings have sent me videos of people busting out into song and like the women playing drums, but I didn’t even realize that until recently, because I’ve never been to Sudan [as an adult]. They had the death penalty up until 2020 for gay people and trans people, so I was scared. I mean, my family members know that I was in [Sex Education], and I don’t think they didn’t care as much, because my auntie Aisha calls me every once in a while on WhatsApp…But I knew that it would be different political terrain for me to be in, physically.

I can’t imagine what it’s like to have such a deeply personal connection to something like that, let alone how emotionally devastating it is to watch everything from afar. Add that to the environmental havoc being caused and the foreign nations feeding into political instability for natural resources, it feels like a lot.

And mainly for a lot of rocks. They just like, want all the minerals and rocks, mainly gold. It’s legitimately scary what’s happening there and the rest of the Continent. I even reference it on “unruly” — “diamonds on my wrist / left blood on my hands” — and all the weapons proliferation in Sudan as a result of the wars. The environmental effects of that, of crops being burnt by both the Rapid Support Forces and the Sudanese Armed Forces, and how [foreign powers] were looking for access to oil in the ‘90s. Now, it’s gold, and Saudi Arabia, Dubai, and other places in the Middle East are seeking out resources from Sudan that are shipped from my home area, Kassala. And that’s the primary cause of political strife within Sudan right now.

Honestly, it’s a little shocking how little attention it’s gotten historically.

I keep thinking about that, and I feel like people don’t really get it. I haven’t really talked publicly about my past before, but I think upwards mobility has really skewed my perception of things.

Rhianna Hajduch

That was something you kind of addressed on your last EP, CROSSOVER. Granted, I also think that’s just what happens with upwards mobility. It gives you a lot more time and energy to intellectualize, because you can focus on more than just surviving day-to-day. You have that extra time to think about the minutiae of the system and obsessively follow news — or just bury your head in the sand.

It’s funny, because I think I perused the news more when I was in survival mode. I think part of it is the laziness that comes along with wealth, because you’re not being directly affected in the way that other people are affected. But that’s also something I think about with myself constantly because, before, I would actively seek out podcasts from people who are more left leaning closer to the socialist perspective. Now, I can just turn on Al-Jazeera or Sky News to see what’s happening. I used to endorse the Green Party and, now, I’m more comfortable talking about the Democratic Party as something that would be more in alignment with what I would want for the kids of the future, which isn’t necessarily how I would have aligned myself In the past.

But I think maybe that’s also rooted in transness as well. As I said before, there’s a lot of fear instilled in my heart as a result of being persecuted, both legislation-wise and in real life, and for trans Black women, trans women, trans men, non-binary people who like are post-op, trans people who are out, people who are pre-op, and anyone who’s publicly honest about their identity. Even trans people who are closeted, or people who eventually find out that they’re trans in some capacity. I’m just scared of what’s going to happen for us. Scared about access to health care, scared about access to education, and even the books being stripped away from people like drag artists. Being unable to even read a wholesome book to kids, and seeing all these things piling up, it’s detrimental to my mental health. And I feel like as a result of that, I see things through upward mobility, and it’s a dilution of my older understanding of self. I am more comfortable in the status quo, which I don’t think is good.

I think it’s hard with this current system, though. Right now, you’re having to choose between outright persecution or slightly less persecution, which is some real end-of-the-world stuff.

Yeah, the thought of an apocalypse feels too real. We’re truly on the brink of it. It’s terrifying.